Lieselott Beschorner

Im Atem der Zeit [In the Breath of Time]

29 Jun - 06 Nov 2022

Lieselott Beschorner, Beinlust, Strumpfobjekt, Gruppensex, around 1980, textile, ca. 100x100x100cm, © Lieselott Beschorner, Wien Museum, photo: Birgit and Peter Kainz

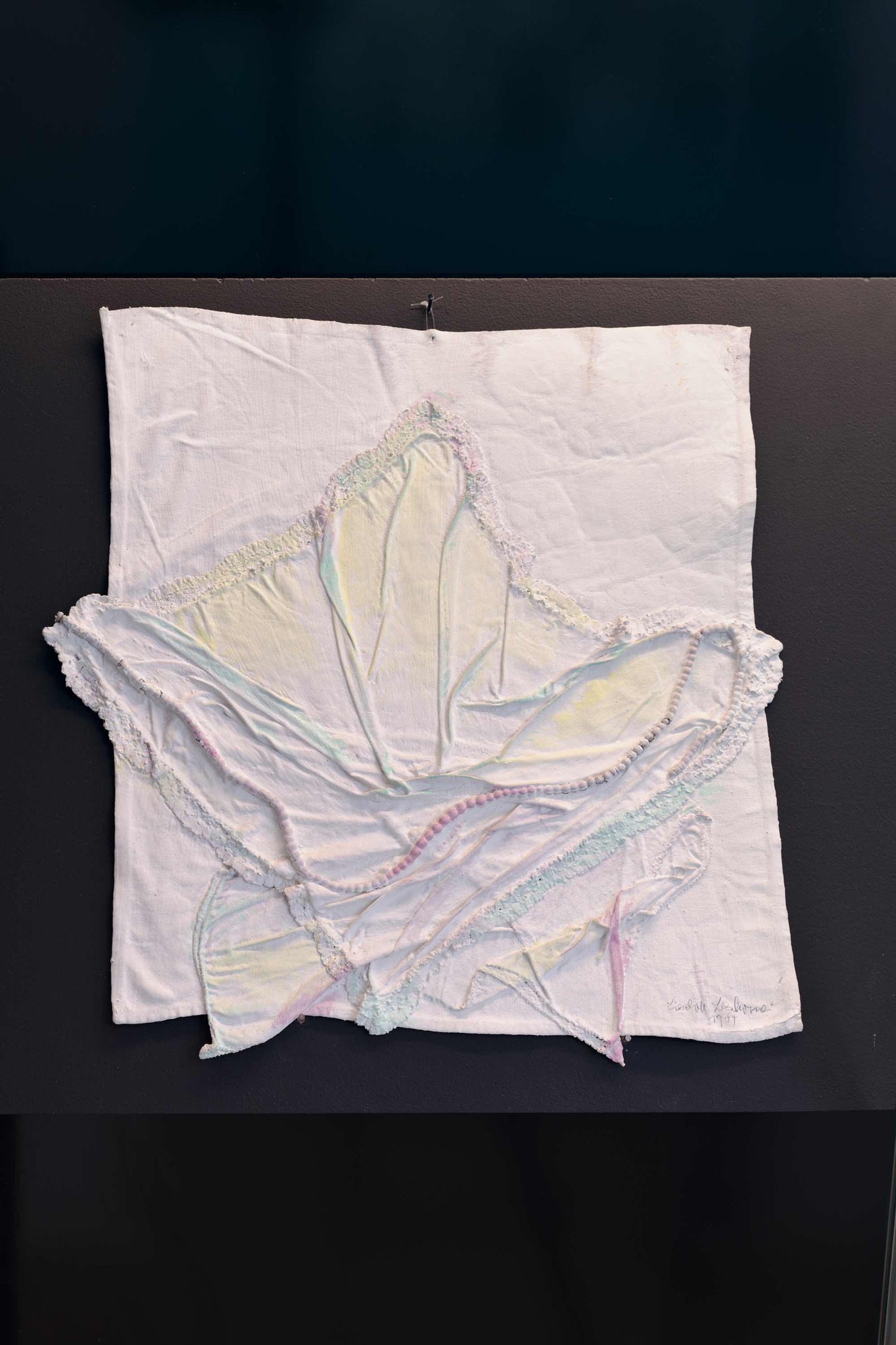

Lieselott Beschorner, Im Atem der Zeit [In the Breath of Time], installation view, Secession 2022, photo: Peter Mochi

Lieselott Beschorner, Im Atem der Zeit [In the Breath of Time], installation view, Secession 2022, photo: Peter Mochi

Lieselott Beschorner, Im Atem der Zeit [In the Breath of Time], installation view, Secession 2022, photo: Peter Mochi

Lieselott Beschorner, Im Atem der Zeit [In the Breath of Time], installation view, Secession 2022, photo: Peter Mochi

Lieselott Beschorner, Im Atem der Zeit [In the Breath of Time], installation view, Secession 2022, photo: Peter Mochi

Lieselott Beschorner, Im Atem der Zeit [In the Breath of Time], installation view, Secession 2022, photo: Peter Mochi

Lieselott Beschorner, Im Atem der Zeit [In the Breath of Time], installation view, Secession 2022, photo: Peter Mochi

Lieselott Beschorner, Im Atem der Zeit [In the Breath of Time], installation view, Secession 2022, photo: Peter Mochi

Lieselott Beschorner, Im Atem der Zeit [In the Breath of Time], installation view, Secession 2022, photo: Peter Mochi

The title of Lieselott Beschorner’s exhibition, Im Atem der Zeit [In the Breath of Time], is a direct reference to the environment in which her work comes into existence. It is only in the now of our days, as in the then of past decades, that her ideas could have taken shape. Their time-bound nature notwithstanding, her art lays claim to a universality that elevates it above its topical concerns and ensures its relevance in the future.

Lieselott Beschorner has made art for over seven decades and been a member of the Vienna Secession for just as long. When she was admitted to the Association of Visual Artists in 1951, she was among the first women members: the Secession, which had been founded in 1897, had remained a male preserve until shortly after the war. Only a few years later, in 1954, Beschorner presented her first exhibition at the Secession, followed by shows in 1966 and 1972, and her work was included in group exhibitions on a regular basis until the mid-1970s. Around that time, the artist took up teaching at a vocational school (she would continue to do so for over thirty years); meanwhile, new tendencies emerged that vied for attention, and her art faded from the spotlight.

Undeterred, Beschorner kept making art with the means at her disposal, building an oeuvre that is as complex as it is eclectic: her output ranges from abstract paintings to expressively representational drawings and collages, from ceramics and textile works—including the body of work that is probably most widely known today, the Puppas—to her most recent sculptures, like the Behutete Kopffiguren [Hatted-Head Figures, 2014], and a vast trove of drawings on the ubiquitous subject of the virus, among them the cycle of Weinende Omnichronisten [Weeping Omnichroniclers, 2022]. A small cross-section of the results of this drawing practice, which continues to the present day, is represented in the exhibition as “wallpaper”. Gathered under the labels of Impuls- or Sekundenzeichnungen [Impulsive or Seconds Drawings], these sheets capture flashes of inspiration, melding gestural eruptions with experience and the artist’s masterful command of the line. Now almost completely blind, she has lost none of her flair for creating dynamic compositions that marry playful lightness to solid structure. Rational considerations are secondary in Beschorner’s oeuvre. She sees her art has a kind of gift that she channels, in an impulsive creative act, into the form of her works. “These works are me,” as she puts it. And just as the artist’s spirit directly informs her production, her fetish-like figures have an air of being inhabited by spirits. Fellow residents of the house, they act as facilitators of communication as well as protectors. The unifying theme that holds these diverse facets of her oeuvre together is the grotesque.

Many of Lieselott Beschorner’s works and techniques anticipated achievements of later generations of women artists, as in the art of Sarah Lucas or Annette Messager; her Puppas even antedate Louise Bourgeois’s ragdolls. The public had few opportunities to take note of her evolving art until a decade ago, when her work was showcased at MUSA. The Secession is excited to host her exhibition Im Atem der Zeit [In the Breath of Time]. Featuring recent creations as well as selected pieces from earlier periods of her oeuvre, it illustrates that Beschorner’s work has lost none of its vitality and still speaks powerfully to contemporary concerns.

Complementing the exhibition is the film Sekundenarbeiten (2021) by Christiana Perschon. This extraordinary portrait shows the artist making her so-called “impulse drawings,” for which she needs about as long as it takes to rewind the filmmaker’s 16mm Bolex. While the images of the artist at work in her studio are rendered in silent black-and-white, the recorded voice of Lieselott Beschorner is accompanied by a black screen.

Programmed by the board of the Secession

Curated by Berthold Ecker and Jeanette Pacher

Lieselott Beschorner has made art for over seven decades and been a member of the Vienna Secession for just as long. When she was admitted to the Association of Visual Artists in 1951, she was among the first women members: the Secession, which had been founded in 1897, had remained a male preserve until shortly after the war. Only a few years later, in 1954, Beschorner presented her first exhibition at the Secession, followed by shows in 1966 and 1972, and her work was included in group exhibitions on a regular basis until the mid-1970s. Around that time, the artist took up teaching at a vocational school (she would continue to do so for over thirty years); meanwhile, new tendencies emerged that vied for attention, and her art faded from the spotlight.

Undeterred, Beschorner kept making art with the means at her disposal, building an oeuvre that is as complex as it is eclectic: her output ranges from abstract paintings to expressively representational drawings and collages, from ceramics and textile works—including the body of work that is probably most widely known today, the Puppas—to her most recent sculptures, like the Behutete Kopffiguren [Hatted-Head Figures, 2014], and a vast trove of drawings on the ubiquitous subject of the virus, among them the cycle of Weinende Omnichronisten [Weeping Omnichroniclers, 2022]. A small cross-section of the results of this drawing practice, which continues to the present day, is represented in the exhibition as “wallpaper”. Gathered under the labels of Impuls- or Sekundenzeichnungen [Impulsive or Seconds Drawings], these sheets capture flashes of inspiration, melding gestural eruptions with experience and the artist’s masterful command of the line. Now almost completely blind, she has lost none of her flair for creating dynamic compositions that marry playful lightness to solid structure. Rational considerations are secondary in Beschorner’s oeuvre. She sees her art has a kind of gift that she channels, in an impulsive creative act, into the form of her works. “These works are me,” as she puts it. And just as the artist’s spirit directly informs her production, her fetish-like figures have an air of being inhabited by spirits. Fellow residents of the house, they act as facilitators of communication as well as protectors. The unifying theme that holds these diverse facets of her oeuvre together is the grotesque.

Many of Lieselott Beschorner’s works and techniques anticipated achievements of later generations of women artists, as in the art of Sarah Lucas or Annette Messager; her Puppas even antedate Louise Bourgeois’s ragdolls. The public had few opportunities to take note of her evolving art until a decade ago, when her work was showcased at MUSA. The Secession is excited to host her exhibition Im Atem der Zeit [In the Breath of Time]. Featuring recent creations as well as selected pieces from earlier periods of her oeuvre, it illustrates that Beschorner’s work has lost none of its vitality and still speaks powerfully to contemporary concerns.

Complementing the exhibition is the film Sekundenarbeiten (2021) by Christiana Perschon. This extraordinary portrait shows the artist making her so-called “impulse drawings,” for which she needs about as long as it takes to rewind the filmmaker’s 16mm Bolex. While the images of the artist at work in her studio are rendered in silent black-and-white, the recorded voice of Lieselott Beschorner is accompanied by a black screen.

Programmed by the board of the Secession

Curated by Berthold Ecker and Jeanette Pacher