Manon de Boer

Giving Time to Time

01 Jul - 28 Aug 2016

MANON DE BOER

Giving Time to Time

1 July – 28 August 2016

Manon de Boer primarily works with film, and her art often subjects the medium itself to critical scrutiny; for example, she insistently probes the interplay between image and sound and questions the power of pictures as well as their claim to truth. Personal narrative and musical interpretation figure as both subjects and methodological registers of de Boer’s filmic portraits, which she composes as slow-paced fluid sequences of images. Most of the protagonists of her films are actors and actresses, musicians, dancers, and intellectuals. The characters gradually assume definite shape as their recollections unfold, emerging into view like photographic prints in the darkroom, and even the fully formed picture conceals at least as much as it reveals. In de Boer’s work, what one might describe as the fragmentary or inconsistent quality of narrative not only draws attention to the mutable relationship between time and language; it also highlights the ways in which perception is dependent on the situational context and subject to subtle alterations. The use of voiceover narration adds another layer that transcends the sitter’s physical presence.

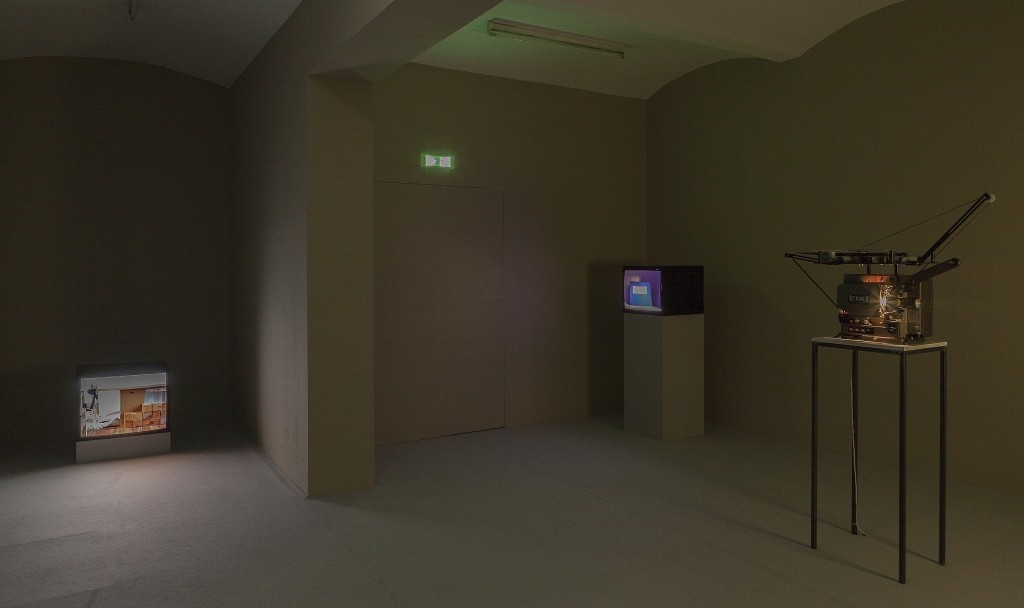

Manon de Boer’s exhibition Giving Time to Time presents six film pieces that reflect the artist’s interest in the conditions in which creativity and unfettered artistic expression flourish. As she sees it, the experience of time as indefinite and open-ended duration and an unburdened mind are crucial: “I regard these moments of aimlessness when you can let your mind wander, forget time, and clear your head as an essential part of the creative process.”

De Boer finds theoretical support for her own observations and experiences in readings such as the work of the British psychoanalyst Marion Milner (1900–1998), who studied creativity extensively, and the writings of the Canadian-American painter and Milner’s contemporary Agnes Martin, whose work she regards highly. Milner’s book An Experiment in Leisure (1937) and Martin’s text The Untroubled Mind (1972), in particular, not only contain interesting and stimulating reflections that inspired de Boer; they have also given two of the films on view in the exhibition their titles.

An Experiment in Leisure (2016), which will have its premiere in an exhibition setting at the Secession, is an attempt to translate the idea of aimless and open-ended time into film. In preparation for the project, de Boer exchanged ideas with friends—artists, choreographers, and theorists—about selected key terms in Milner’s work such as reverie, repetition, rhythm, and malleability. A series of sequence shots—long uncut takes recorded with a stationary camera—survey the vast deserted landscape of an island on different days but from an unvarying perspective. Slow tracking shots then direct our attention to details shown in close-up that bring abstract painting to mind, intercut with views of the workplaces of de Boer’s interlocutors: ateliers, dance studios, a library—oblique portraits of their denizens, who are present solely by virtue of their voices and the traces of their activities. The reduction to these calm and expressive pictures—some of the shots might seem like freeze-frames, were it not for subtle changes such as soft ripples on a water surface, a swaying curtain, or the play of light and shadow—slows perception down to the threshold of boredom to generate a state of heightened sensibility and wide-awakeness. The soundtrack consists of a continuous soundscape recorded as the artist was shooting in northern Europe. Now and then offscreen voices layer the natural sounds, fragments from the conversations about Milner, marking positions of a sort amid the constant abstract sonic flow that promotes the desired mental state of drifting and free association.

In addition to the portraits Presto, Perfect Sound (2006) and Dissonant (2010), two structural films that operate with repetition and variation and are shown in turns, the exhibition features three recently completed films: the “film sketches” The Untroubled Mind (2013–2016) and You Can Never Be Complete (2015), which make their public premiere at the Secession, and the 16mm film installation Maud Capturing the Light ‘On a Clear Day’ (2015).

Presto, Perfect Sound and Dissonant are portraits of the musician George van Dam and the dancer Cynthia Loemij, respectively. Of particular interest in the context of the exhibition, de Boer suggests, is the pure concentration that speaks from their faces as they perform. This expression of utter focus, the artist says, is the ideal embodiment of what Milner wrote about forms of thinking and free association and how, when the perception of the inner and the outside world coincide, they often give rise to a powerful experience of space and time.

Maud Capturing the Light ‘On a Clear Day,’ meanwhile, is a filmic study of a drawing by Agnes Martin, ‘On a Clear Day,’ and its changing aspect in everyday life in a private setting. She asked the owner—who appears in the film only as a transient reflection in the glass protecting the picture—to record the drawing that hangs in her hallway whenever it attracted her attention, as due to special lighting atmospheres.

The presence of the protagonists in the two silent film “sketches” is felt only by virtue of the presentation of a potentially infinite collection in one and traces of carefree pursuits in the other, respectively. In You Can Never Be Complete (2015), we see a series of shots of the same unvarying part of a bookshelf on which a succession of books appear that figure prominently in the history of Western culture and ideas: writings by and about Palladio, Arendt/Benjamin, Warburg, Giotto, Judd, Bataille, Rilke, Didi-Huberman, Daedalus, Le Corbusier, Melville, and others. They are taken from the collection of the Belgian publisher and art historian Yves Gevaert, with whom the artist has carried on an ongoing conversation about collecting and associative connections between art, literature, music, and philosophy since 2014.

The scenes in The Untroubled Mind were shot with a Bolex, a 16mm amateur camera that needs to be wound up manually before shooting sequences of around 20 seconds. Making reference to the eponymous essay by Agnes Martin, the film paints a serene portrait of the many untroubled moments of discovery and active creative engagement with the world in a child’s life. Whenever the artist spotted such surprising manifestations or gestures of an enviably blithe mental state in her son, she took the Bolex and documented the playful ease with which he put materials and space to unorthodox uses: sometimes firmly tied, sometimes less dependable webs of strings strung from chairs to the table or window, a cloth slung over them; a tower of building bricks, with jackstraws laid over them for bridges; stacks of coins leaning against chair legs; paths through the apartment marked by repurposed metal parts, etc. The Untroubled Mind reveals a wonderfully fresh and refreshing perspective on the world and the potential that lies in a moment of passivity, of boredom, or leisure—when we allow ourselves to experience it.

As she worked on the exhibition, Manon de Boer also conceived and designed the artist’s book Trails and Traces. It includes stills from the films on view in the exhibition as well as excerpts from the conversations about Marion Milner and her theories and other relevant writings on related issues.

Giving Time to Time

1 July – 28 August 2016

Manon de Boer primarily works with film, and her art often subjects the medium itself to critical scrutiny; for example, she insistently probes the interplay between image and sound and questions the power of pictures as well as their claim to truth. Personal narrative and musical interpretation figure as both subjects and methodological registers of de Boer’s filmic portraits, which she composes as slow-paced fluid sequences of images. Most of the protagonists of her films are actors and actresses, musicians, dancers, and intellectuals. The characters gradually assume definite shape as their recollections unfold, emerging into view like photographic prints in the darkroom, and even the fully formed picture conceals at least as much as it reveals. In de Boer’s work, what one might describe as the fragmentary or inconsistent quality of narrative not only draws attention to the mutable relationship between time and language; it also highlights the ways in which perception is dependent on the situational context and subject to subtle alterations. The use of voiceover narration adds another layer that transcends the sitter’s physical presence.

Manon de Boer’s exhibition Giving Time to Time presents six film pieces that reflect the artist’s interest in the conditions in which creativity and unfettered artistic expression flourish. As she sees it, the experience of time as indefinite and open-ended duration and an unburdened mind are crucial: “I regard these moments of aimlessness when you can let your mind wander, forget time, and clear your head as an essential part of the creative process.”

De Boer finds theoretical support for her own observations and experiences in readings such as the work of the British psychoanalyst Marion Milner (1900–1998), who studied creativity extensively, and the writings of the Canadian-American painter and Milner’s contemporary Agnes Martin, whose work she regards highly. Milner’s book An Experiment in Leisure (1937) and Martin’s text The Untroubled Mind (1972), in particular, not only contain interesting and stimulating reflections that inspired de Boer; they have also given two of the films on view in the exhibition their titles.

An Experiment in Leisure (2016), which will have its premiere in an exhibition setting at the Secession, is an attempt to translate the idea of aimless and open-ended time into film. In preparation for the project, de Boer exchanged ideas with friends—artists, choreographers, and theorists—about selected key terms in Milner’s work such as reverie, repetition, rhythm, and malleability. A series of sequence shots—long uncut takes recorded with a stationary camera—survey the vast deserted landscape of an island on different days but from an unvarying perspective. Slow tracking shots then direct our attention to details shown in close-up that bring abstract painting to mind, intercut with views of the workplaces of de Boer’s interlocutors: ateliers, dance studios, a library—oblique portraits of their denizens, who are present solely by virtue of their voices and the traces of their activities. The reduction to these calm and expressive pictures—some of the shots might seem like freeze-frames, were it not for subtle changes such as soft ripples on a water surface, a swaying curtain, or the play of light and shadow—slows perception down to the threshold of boredom to generate a state of heightened sensibility and wide-awakeness. The soundtrack consists of a continuous soundscape recorded as the artist was shooting in northern Europe. Now and then offscreen voices layer the natural sounds, fragments from the conversations about Milner, marking positions of a sort amid the constant abstract sonic flow that promotes the desired mental state of drifting and free association.

In addition to the portraits Presto, Perfect Sound (2006) and Dissonant (2010), two structural films that operate with repetition and variation and are shown in turns, the exhibition features three recently completed films: the “film sketches” The Untroubled Mind (2013–2016) and You Can Never Be Complete (2015), which make their public premiere at the Secession, and the 16mm film installation Maud Capturing the Light ‘On a Clear Day’ (2015).

Presto, Perfect Sound and Dissonant are portraits of the musician George van Dam and the dancer Cynthia Loemij, respectively. Of particular interest in the context of the exhibition, de Boer suggests, is the pure concentration that speaks from their faces as they perform. This expression of utter focus, the artist says, is the ideal embodiment of what Milner wrote about forms of thinking and free association and how, when the perception of the inner and the outside world coincide, they often give rise to a powerful experience of space and time.

Maud Capturing the Light ‘On a Clear Day,’ meanwhile, is a filmic study of a drawing by Agnes Martin, ‘On a Clear Day,’ and its changing aspect in everyday life in a private setting. She asked the owner—who appears in the film only as a transient reflection in the glass protecting the picture—to record the drawing that hangs in her hallway whenever it attracted her attention, as due to special lighting atmospheres.

The presence of the protagonists in the two silent film “sketches” is felt only by virtue of the presentation of a potentially infinite collection in one and traces of carefree pursuits in the other, respectively. In You Can Never Be Complete (2015), we see a series of shots of the same unvarying part of a bookshelf on which a succession of books appear that figure prominently in the history of Western culture and ideas: writings by and about Palladio, Arendt/Benjamin, Warburg, Giotto, Judd, Bataille, Rilke, Didi-Huberman, Daedalus, Le Corbusier, Melville, and others. They are taken from the collection of the Belgian publisher and art historian Yves Gevaert, with whom the artist has carried on an ongoing conversation about collecting and associative connections between art, literature, music, and philosophy since 2014.

The scenes in The Untroubled Mind were shot with a Bolex, a 16mm amateur camera that needs to be wound up manually before shooting sequences of around 20 seconds. Making reference to the eponymous essay by Agnes Martin, the film paints a serene portrait of the many untroubled moments of discovery and active creative engagement with the world in a child’s life. Whenever the artist spotted such surprising manifestations or gestures of an enviably blithe mental state in her son, she took the Bolex and documented the playful ease with which he put materials and space to unorthodox uses: sometimes firmly tied, sometimes less dependable webs of strings strung from chairs to the table or window, a cloth slung over them; a tower of building bricks, with jackstraws laid over them for bridges; stacks of coins leaning against chair legs; paths through the apartment marked by repurposed metal parts, etc. The Untroubled Mind reveals a wonderfully fresh and refreshing perspective on the world and the potential that lies in a moment of passivity, of boredom, or leisure—when we allow ourselves to experience it.

As she worked on the exhibition, Manon de Boer also conceived and designed the artist’s book Trails and Traces. It includes stills from the films on view in the exhibition as well as excerpts from the conversations about Marion Milner and her theories and other relevant writings on related issues.