Nicole Eisenman

Dark Light

14 Sep - 05 Nov 2017

Nicole Eisenman, Shooter 2, 2016, 208,28 x 165,1 cm. Courtesy the artist, Anton Kern Gallery NY and The Daskal Collection, Photo: Sophie Thun

Nicole Eisenman rose to renown in the New York art world in the 1990s as a creator of epic visual universes and inventor of bold, unvarnished, and occasionally shocking tableaus. She surveys the history of modern-era painting with instinctive assurance, rendering fantastic scenes as well as astute observations from everyday life in compelling form. Despite her stylistic versatility—she deliberately thwarts attempts to pigeonhole and fence her in—Eisenman has developed a unique signature style blending classical techniques and compositional forms with influences from underground and popular culture. The private clashes with the political in works that sometimes feature her own friends and acquaintances, a forthrightness that has made her a leading protagonist in contemporary art and the queer art scene.

Most recently, Eisenman caused a stir with her reinterpretation of a baroque fountain for Skulptur Projekte Münster. At the Secession, she presents paintings and drawings from the past year that respond directly to last fall’s U. S. presidential elections. Recalling earlier works in which apocalyptic scenes reflected relations of power and the individual’s impuissance, the new cycle paints a gloomy panorama of America under Donald Trump and a society that, apathetic and absent-minded, is edging ever closer to the abyss.

The centerpieces of the exhibition, the titular Dark Light and Going Down River on the USS J-Bone of an Ass, are two monumental and highly elaborate compositions that could hardly be more different.

Dark Light (2017) shows a man wearing a red baseball cap standing on the bed of a pickup truck; three others around him are fast asleep. His outstretched right arm holds a flashlight from which a powerful cone of blackish-blue light extends beyond the field of view. A cloud of thick black smoke billows from a silvery-gleaming pipe that towers above him, while a black liquid—presumably an allusion to crude oil—wells from a circular opening in the sky surrounded by halos.

On the surface, the reference is to “rolling coal,” a practice that has recently sprung up in the United States in which diesel vehicles, usually pickup trucks, are modified so that at the push of a button more fuel is injected into the engine than can be burned, releasing an infernal cloud of black sooty exhaust. Outside of dedicated contests in which enthusiasts demonstrate their prowess, “coal rolling” is preferably triggered against bicyclists, pedestrians, and hybrid vehicles; it has also been used to dispel anti-Trump demonstrations by dousing the protesters with highly noxious diesel exhaust fumes. When then president Barack Obama pushed for greater environmental regulation and climate protection, the political wing of this “hobby movement” took a clear stance that can be summed up as “If Obama is for the environment, we’re against it.” Relations with the current president are more cordial, as the red baseball cap worn by the “leader” suggests: such caps with the slogan “Make America Great Again” were omnipresent during the campaign.

Going Down River on the USS J-Bone of an Ass (2017), though more enigmatic, is no less sinister. Unlike Dark Light, where large flat surfaces predominate and all elements are arrayed on a single plane in the foreground, this second picture boasts are more detail-rich composition, with elements staggered at different depths and a landscape characterized in a style that recalls the Italian trecento. Several objects and a boat are drifting toward a chasm where the water crashes into a bottomless depth. A floating giant mandible (the j-bone of the title) carries a man with a flute, a sailor, and a businessman in a suit—an echo of George Grosz’s bankers and businessmen that make cameos in many of Eisenman’s earlier works. The piper pipes, the drummer (in the red boat) drums, and everyone is eerily calm, unconcerned, or even asleep, like the group of men in the boat, who bear some resemblance to the “disciples” on the truck. Amid the other elements, a squirrel, an acorn in its paws, is swimming toward the precipice. The scene’s serenity is unsettling: a dramatic and fateful event is imminent and inevitable, and the viewer can easily imagine the outcome.

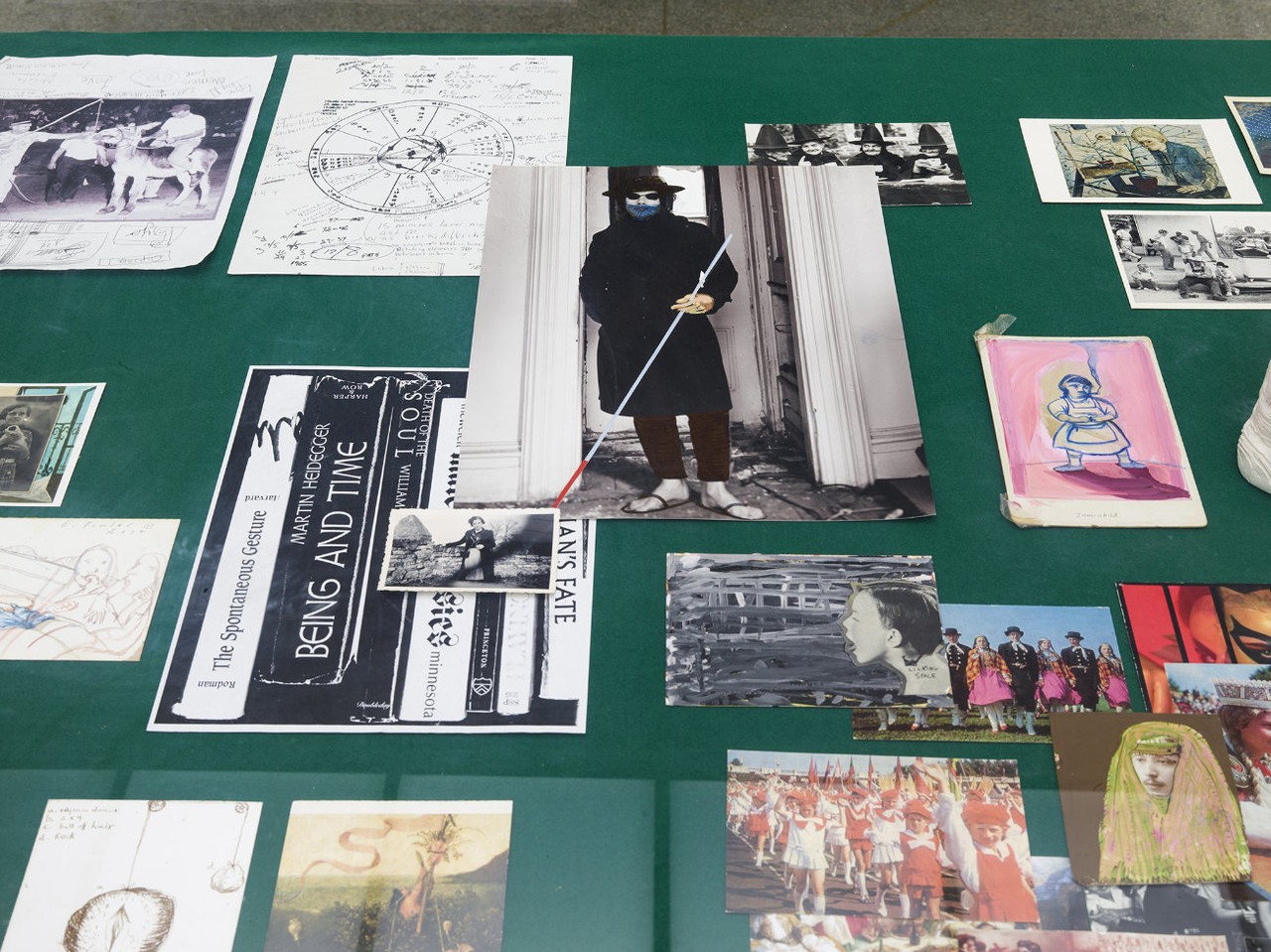

Besides the new paintings, Eisenman’s show at the Secession also includes drawings, most of them studies and preparatory sketches. Offering the visitor insight into her creative process, these graphic works are a secret highlight of the presentation. One drawing, for example, unites the central element in the two paintings while also illuminating the—formal as well as substantial—affinities with a third work in the exhibition, Shooter 2 (2016): a largely abstract composition in garish colors in which the barrel of a gun, pointing directly at the viewer, makes for a sight of shockingly violent immediacy. The drawings reveal continuities of form and composition in Eisenman’s studies that would not be so readily discernibly in the finished paintings.

Most recently, Eisenman caused a stir with her reinterpretation of a baroque fountain for Skulptur Projekte Münster. At the Secession, she presents paintings and drawings from the past year that respond directly to last fall’s U. S. presidential elections. Recalling earlier works in which apocalyptic scenes reflected relations of power and the individual’s impuissance, the new cycle paints a gloomy panorama of America under Donald Trump and a society that, apathetic and absent-minded, is edging ever closer to the abyss.

The centerpieces of the exhibition, the titular Dark Light and Going Down River on the USS J-Bone of an Ass, are two monumental and highly elaborate compositions that could hardly be more different.

Dark Light (2017) shows a man wearing a red baseball cap standing on the bed of a pickup truck; three others around him are fast asleep. His outstretched right arm holds a flashlight from which a powerful cone of blackish-blue light extends beyond the field of view. A cloud of thick black smoke billows from a silvery-gleaming pipe that towers above him, while a black liquid—presumably an allusion to crude oil—wells from a circular opening in the sky surrounded by halos.

On the surface, the reference is to “rolling coal,” a practice that has recently sprung up in the United States in which diesel vehicles, usually pickup trucks, are modified so that at the push of a button more fuel is injected into the engine than can be burned, releasing an infernal cloud of black sooty exhaust. Outside of dedicated contests in which enthusiasts demonstrate their prowess, “coal rolling” is preferably triggered against bicyclists, pedestrians, and hybrid vehicles; it has also been used to dispel anti-Trump demonstrations by dousing the protesters with highly noxious diesel exhaust fumes. When then president Barack Obama pushed for greater environmental regulation and climate protection, the political wing of this “hobby movement” took a clear stance that can be summed up as “If Obama is for the environment, we’re against it.” Relations with the current president are more cordial, as the red baseball cap worn by the “leader” suggests: such caps with the slogan “Make America Great Again” were omnipresent during the campaign.

Going Down River on the USS J-Bone of an Ass (2017), though more enigmatic, is no less sinister. Unlike Dark Light, where large flat surfaces predominate and all elements are arrayed on a single plane in the foreground, this second picture boasts are more detail-rich composition, with elements staggered at different depths and a landscape characterized in a style that recalls the Italian trecento. Several objects and a boat are drifting toward a chasm where the water crashes into a bottomless depth. A floating giant mandible (the j-bone of the title) carries a man with a flute, a sailor, and a businessman in a suit—an echo of George Grosz’s bankers and businessmen that make cameos in many of Eisenman’s earlier works. The piper pipes, the drummer (in the red boat) drums, and everyone is eerily calm, unconcerned, or even asleep, like the group of men in the boat, who bear some resemblance to the “disciples” on the truck. Amid the other elements, a squirrel, an acorn in its paws, is swimming toward the precipice. The scene’s serenity is unsettling: a dramatic and fateful event is imminent and inevitable, and the viewer can easily imagine the outcome.

Besides the new paintings, Eisenman’s show at the Secession also includes drawings, most of them studies and preparatory sketches. Offering the visitor insight into her creative process, these graphic works are a secret highlight of the presentation. One drawing, for example, unites the central element in the two paintings while also illuminating the—formal as well as substantial—affinities with a third work in the exhibition, Shooter 2 (2016): a largely abstract composition in garish colors in which the barrel of a gun, pointing directly at the viewer, makes for a sight of shockingly violent immediacy. The drawings reveal continuities of form and composition in Eisenman’s studies that would not be so readily discernibly in the finished paintings.