Thomas Ruff

New Works

07 Jul - 02 Sep 2017

Thomas Ruff

press++50.08, 2016

C-print

237 x 185 cm

© Thomas Ruff / VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn, 2017

Courtesy Sprüth Magers

press++50.08, 2016

C-print

237 x 185 cm

© Thomas Ruff / VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn, 2017

Courtesy Sprüth Magers

Sprüth Magers is pleased to present Thomas Ruff’s first exhibition at the gallery with works from his

latest press++ series, all of which are exhibited here for the first time. In a multi-faceted practice that

examines the ever-changing possibilities of photography, Ruff’s investigations into visual and cultural

phenomena are indebted to an interest in how technology makes us see. This is evident in his vast

array of subjects and methods, from portraiture and astronomical documentation to photograms and

digital abstractions created by algorithms.

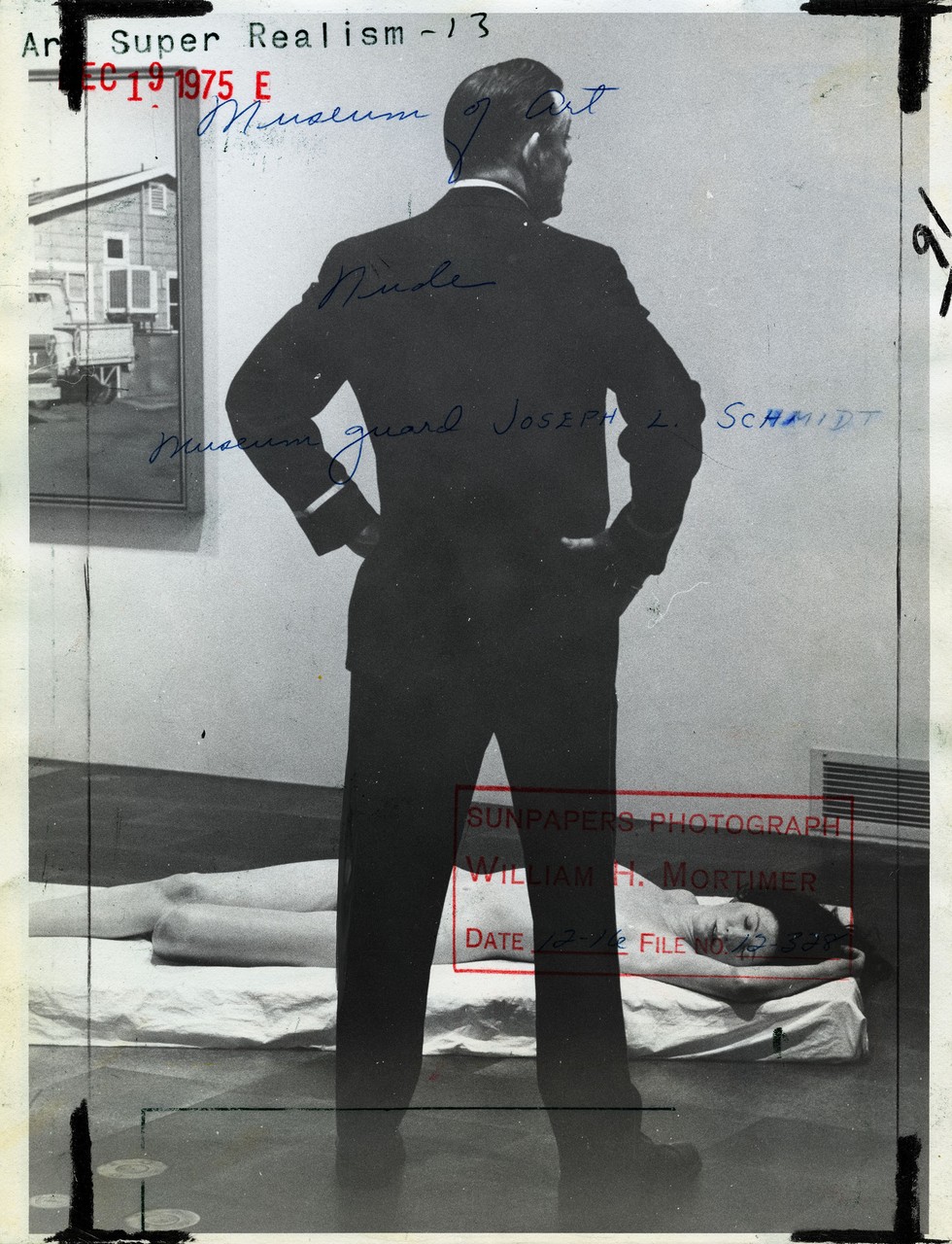

Images that have been published in American newspapers and magazines from the 1920s to 1970s

are Ruff’s source material for his press++ series, images that in themselves have even more diverse

archival origins; the police, NASA, press agencies and press departments of institutions, to name a

few. From the 1930s onwards, most of the photographs were no longer sent by mail from the press

agency to the newspapers but instead sent as a wire and were then printed out by the newspaper,

therefore showing the structure of the wire transmission.

To produce these works, Ruff scans the front and back of each photograph and combines them

digitally, taking into account the original image as well as crops, touch-ups, date stamps, scribbles and

smudges. Each of these marks varies in line, colour, and implement used; a red stamp, an inky blue

fingerprint, a biro squiggle. Ruff has commented how photo-editors at the newspapers had little

respect for the photograph, significantly altering the look and meaning of the original with their

retouching and comments. Despite how invisible the hand of the editor is typically made to seem, here

they are placed front and centre.

The unmistakable porcelain skin and sultry glare of silver screen sirens redolent in their inimitable

Hollywood glamour populate the main gallery space. The source photographs for these works are the

publicity shots used by casting agencies to promote the actresses on their books, with names

scrawled on the reverse to identify them; Portland Mason, Connie Russell, Rosemary Clooney. Their

faces are interrupted by paint enhancing contours or attached clippings of their final published version,

for example the announcement for a new play starring the actress, creating a ghostly repetition within

the image. Other images are more sparse, just a handwritten name to identify the subject or a frantic

tick to indicate the approval of the editor.

Another collection of works examines the images handed out by press departments of museums. A

large stamp across a Joan Miró painting identifies its source as the Guggenheim, this textual addition

intermingling with the artist’s own, meandering marks. The text may also detail the route of the photograph; a stamp reads ‘Please return to the Baltimore Museum of Art’, and a pencil note ‘Sunday Sun Feature Sect.’ tells us where it was published. The credibility of annotations and printed text on the image cannot always be trusted however, with a Chuck Close image labelled as Jasper Johns. Was this published incorrectly, or is this just a mix-up on file?

Changes made by editors compromise the original image but also add the relevant context and show

how it has been changed for its purpose, allowing the study of the historical, political and social

context in which an image is produced and how it’s meaning can be interfered with and altered. There

is also a strong resemblance to the Dada photomontages of the 1920s but without the surrealistic

effects and political intent of these forbearers. For Ruff, the redistribution and rearchiving of the

photographic image, which has been a core premise of his practice for many years, presents a

number of problems in terms of truth and integrity. In these latest works, which make their debut in the

exhibition, the image comes to be considered in terms of artistic value when it is slowly severed from

its source, the information contained in it as a press image ebbing away.

Thomas Ruff (*1958 in Zell am Harmersbach, Germany) lives and works in Düsseldorf. He studied at

the Staatliche Kunstakademie, Düsseldorf from 1977 to 1985. Recent solo exhibitions include the the

National Museum of Modern Art, Tokyo, travelled to the 21st Century Museum of Contemporary,

Kanazawa, (both 2016); Art Gallery of Ontario, Toronto (2016); S.M.A.K., Gent, travelled to the

Kunsthalle Düsseldorf (both 2014); and the Haus der Kunst, Munich (2012). In September 2017 a

major exhibition of his work will open at the Whitechapel Gallery, London.

The Berlin gallery is concurrently presenting exhibitions by Analia Saban and Thea Djordjadze,

Rosemarie Trockel.

For further information and press enquiries, please contact Silvia Baltschun

(sb@spruethmagers.com)

latest press++ series, all of which are exhibited here for the first time. In a multi-faceted practice that

examines the ever-changing possibilities of photography, Ruff’s investigations into visual and cultural

phenomena are indebted to an interest in how technology makes us see. This is evident in his vast

array of subjects and methods, from portraiture and astronomical documentation to photograms and

digital abstractions created by algorithms.

Images that have been published in American newspapers and magazines from the 1920s to 1970s

are Ruff’s source material for his press++ series, images that in themselves have even more diverse

archival origins; the police, NASA, press agencies and press departments of institutions, to name a

few. From the 1930s onwards, most of the photographs were no longer sent by mail from the press

agency to the newspapers but instead sent as a wire and were then printed out by the newspaper,

therefore showing the structure of the wire transmission.

To produce these works, Ruff scans the front and back of each photograph and combines them

digitally, taking into account the original image as well as crops, touch-ups, date stamps, scribbles and

smudges. Each of these marks varies in line, colour, and implement used; a red stamp, an inky blue

fingerprint, a biro squiggle. Ruff has commented how photo-editors at the newspapers had little

respect for the photograph, significantly altering the look and meaning of the original with their

retouching and comments. Despite how invisible the hand of the editor is typically made to seem, here

they are placed front and centre.

The unmistakable porcelain skin and sultry glare of silver screen sirens redolent in their inimitable

Hollywood glamour populate the main gallery space. The source photographs for these works are the

publicity shots used by casting agencies to promote the actresses on their books, with names

scrawled on the reverse to identify them; Portland Mason, Connie Russell, Rosemary Clooney. Their

faces are interrupted by paint enhancing contours or attached clippings of their final published version,

for example the announcement for a new play starring the actress, creating a ghostly repetition within

the image. Other images are more sparse, just a handwritten name to identify the subject or a frantic

tick to indicate the approval of the editor.

Another collection of works examines the images handed out by press departments of museums. A

large stamp across a Joan Miró painting identifies its source as the Guggenheim, this textual addition

intermingling with the artist’s own, meandering marks. The text may also detail the route of the photograph; a stamp reads ‘Please return to the Baltimore Museum of Art’, and a pencil note ‘Sunday Sun Feature Sect.’ tells us where it was published. The credibility of annotations and printed text on the image cannot always be trusted however, with a Chuck Close image labelled as Jasper Johns. Was this published incorrectly, or is this just a mix-up on file?

Changes made by editors compromise the original image but also add the relevant context and show

how it has been changed for its purpose, allowing the study of the historical, political and social

context in which an image is produced and how it’s meaning can be interfered with and altered. There

is also a strong resemblance to the Dada photomontages of the 1920s but without the surrealistic

effects and political intent of these forbearers. For Ruff, the redistribution and rearchiving of the

photographic image, which has been a core premise of his practice for many years, presents a

number of problems in terms of truth and integrity. In these latest works, which make their debut in the

exhibition, the image comes to be considered in terms of artistic value when it is slowly severed from

its source, the information contained in it as a press image ebbing away.

Thomas Ruff (*1958 in Zell am Harmersbach, Germany) lives and works in Düsseldorf. He studied at

the Staatliche Kunstakademie, Düsseldorf from 1977 to 1985. Recent solo exhibitions include the the

National Museum of Modern Art, Tokyo, travelled to the 21st Century Museum of Contemporary,

Kanazawa, (both 2016); Art Gallery of Ontario, Toronto (2016); S.M.A.K., Gent, travelled to the

Kunsthalle Düsseldorf (both 2014); and the Haus der Kunst, Munich (2012). In September 2017 a

major exhibition of his work will open at the Whitechapel Gallery, London.

The Berlin gallery is concurrently presenting exhibitions by Analia Saban and Thea Djordjadze,

Rosemarie Trockel.

For further information and press enquiries, please contact Silvia Baltschun

(sb@spruethmagers.com)