Constructing The New Man

27 Jan - 30 Apr 2017

CONSTRUCTING THE NEW MAN

27 January - 30 April 2017

The Russian Revolution took place a hundred years ago. The Stedelijk commemorates its centenary in a presentation featuring posters, printed matter, films and art from the collection.

Following the Russian Revolution and the subsequent civil war (1917-1922), the regime introduced economic reforms, utilising posters and film as powerful propaganda tools. As an art form, film developed rapidly after the revolution. Over a hundred films from all over the world were released each year, together with films by Russian directors like Sergei Eisenstein and Dziga Vertov.

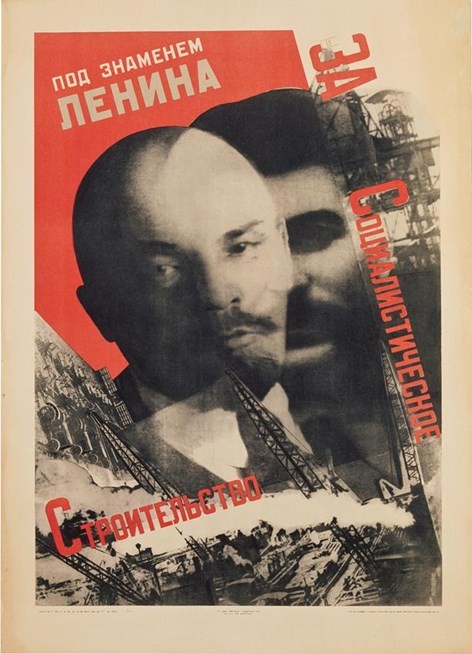

Posters – which were an integral part of everyday life – were an attractive medium to artists dedicated to building the Socialist society. Some felt that the traditional satirical cartoon was the best way to reach the proletariat. Others used photographic and cinematic editing techniques in a new, Constructivist visual language. The collage style was hoped to inspire ordinary people to actively engage with the image, and think deeply about the message conveyed. But this hope soon proved unfounded and, realising that the photomontage had limited appeal for the masses, in 1932 Stalin rejected it as obscure ‘formalism’, replacing it with a documentary Socialist realism that centred around the heroic portrayal of the new Soviet man.

The oldest Russian political poster in the collection of the Stedelijk Museum in the exhibition is an instruction for soldiers of the Red Army, and dates from 1918. Also on display are political posters, many of which were produced in the 1920s and ’30s. The book covers and typography included in the presentation also explore social themes. Marking the era of the revolution is a painting by Kazimir Malevich (1917-1918), and the film October (1927) by Sergei Eisenstein, with the famous scene of the storming of the Winter Palace in Saint Petersburg.

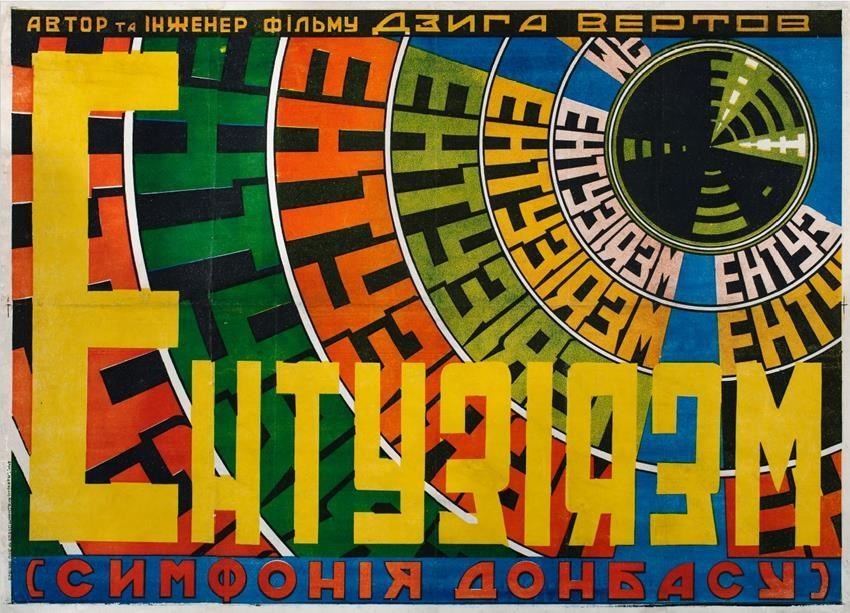

The Kazimir Malevich painting Construction in Dissolution (1918) hangs next to a selection of film posters. This same gallery also features two full-length films: the comic film The Three Million Trial (1926) by Yakov Protazanov (which, despite being declared too Western by the censor, was not banned), and Enthusiasm: Symphony of the Donbas (1931) by Dziga Vertov, the first Russian film with an audio montage of industrial and documentary sounds.

27 January - 30 April 2017

The Russian Revolution took place a hundred years ago. The Stedelijk commemorates its centenary in a presentation featuring posters, printed matter, films and art from the collection.

Following the Russian Revolution and the subsequent civil war (1917-1922), the regime introduced economic reforms, utilising posters and film as powerful propaganda tools. As an art form, film developed rapidly after the revolution. Over a hundred films from all over the world were released each year, together with films by Russian directors like Sergei Eisenstein and Dziga Vertov.

Posters – which were an integral part of everyday life – were an attractive medium to artists dedicated to building the Socialist society. Some felt that the traditional satirical cartoon was the best way to reach the proletariat. Others used photographic and cinematic editing techniques in a new, Constructivist visual language. The collage style was hoped to inspire ordinary people to actively engage with the image, and think deeply about the message conveyed. But this hope soon proved unfounded and, realising that the photomontage had limited appeal for the masses, in 1932 Stalin rejected it as obscure ‘formalism’, replacing it with a documentary Socialist realism that centred around the heroic portrayal of the new Soviet man.

The oldest Russian political poster in the collection of the Stedelijk Museum in the exhibition is an instruction for soldiers of the Red Army, and dates from 1918. Also on display are political posters, many of which were produced in the 1920s and ’30s. The book covers and typography included in the presentation also explore social themes. Marking the era of the revolution is a painting by Kazimir Malevich (1917-1918), and the film October (1927) by Sergei Eisenstein, with the famous scene of the storming of the Winter Palace in Saint Petersburg.

The Kazimir Malevich painting Construction in Dissolution (1918) hangs next to a selection of film posters. This same gallery also features two full-length films: the comic film The Three Million Trial (1926) by Yakov Protazanov (which, despite being declared too Western by the censor, was not banned), and Enthusiasm: Symphony of the Donbas (1931) by Dziga Vertov, the first Russian film with an audio montage of industrial and documentary sounds.