Maneuver

18 Sep - 14 Dec 2019

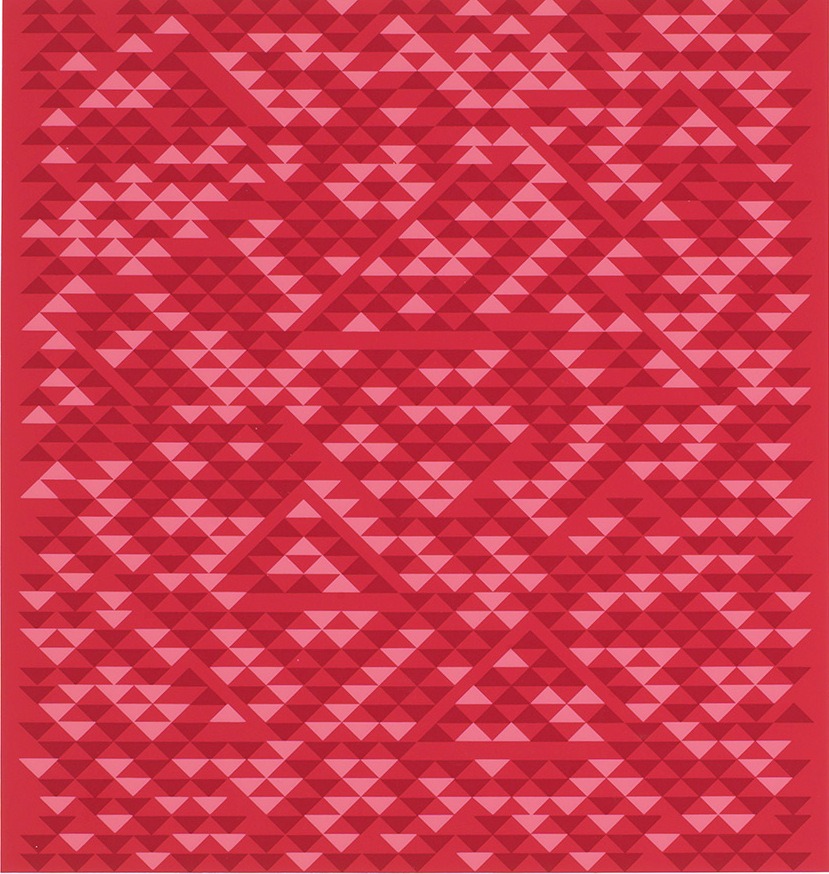

Anni Albers

Camino Real, 1969

screenprint on paper

23 1/2 x 22 inches

The Josef and Anni Albers Foundation, 1994.11.6

Photo: Tim Nighswander/Imaging4Art

© 2019 The Josef and Anni Albers Foundation/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Camino Real, 1969

screenprint on paper

23 1/2 x 22 inches

The Josef and Anni Albers Foundation, 1994.11.6

Photo: Tim Nighswander/Imaging4Art

© 2019 The Josef and Anni Albers Foundation/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

MANEUVER

18 September – 14 December 2019

Anni Albers

Polly Apfelbaum

Sarah Charlesworth

Zoe Leonard

Ed Rossbach

Rosemarie Trockel

curated by Lynne Cooke

Among the greatest weavers of the past century, Anni Albers today is more often encountered through her texts than her textiles. In 1965 she published On Weaving, a magisterial publication that drew on her deep knowledge of this artform. Neither a tract for specialists nor a how-to book, it was intended for readers far-beyond the world of textile practitioners. Now a classic in its field, On Weaving achieved its broad readership by dint of setting forth in concise lucid prose what Albers deemed the principles of woven form. Though coincident with a protean moment of experimentation in off-loom techniques and volumetric free-standing forms, her stance was unyielding: weaving, one the most ancient crafts, remained “essentially unchanged to this day.” Hand-loom weaving, defined as the making of a pliable plane from a structural grid of rectangularly interlaced threads, was, moreover, unequivocally “modern,” and so could serve modern needs, whether those of industry, craft or art. Its structural framework of interlaced soft fibers is, “also the formative framework: woven forms of whatever sort retain always this horizontal vertical character that goes back to their origin.” On Weaving’s copious illustrations—textiles by the great pre-Columbian weavers of Peru, samples of contemporary drapery and upholstery yardage, and fabric made with related techniques such as twining, knotting, looping and braiding—are supplemented by numerous diagrams, above all, by draft notations. Grid-based graphs that record basic weaving structures, these draft notations, in turn, evoke other forms of abstraction, most obviously abstract painting. For it was the grid, with its formal and structural autonomy, Rosalind Krauss contended, that declared “the modernity of modernist art.”

Grey Scale 1 and 2, 2015, embody Polly Apfelbaum’s fascination with a popular mid-century reference book featuring draft notations of traditional American weaving patterns. Each of her paired wall hangings comprises a checkerboard, every unit of which limns a different abstract design mapped out in ink dots with the aid of a plastic stencil. Randomly running the gamut of the dark/light spectrum, inflected with the accidents of manual application, they contest the conformity implicit in geometric order and standardization.

Apfelbaum’s delight in the decorative and tactile, no less than in the grid’s tolerances, is shared by Ed Rossbach, whose Damask Waterfall, 1977, similarly tests the checkboard’s presumption of strict regularity. For the most part, Rossbach cleaved, as did Albers, to that near-timeless conception of the hand-loomed textile as a rectilinear pliable plane, in opposition to the contemporary vanguard cohort who generated the more freewheeling fiber art movement of the 1960s. Also like Albers, Rossbach was an avid student of techniques and forms from diverse cultures, past and present, which he explored in both his writing and his textile practice. As drawn to forms of experimentation that tested the bounds of normative notions as to the recuperation and preservation of traditional modes, Rossbach engaged a plethora of humble materials in his weavings, as well as in basketry, which he deemed “a textile art” in the title of a seminal publication. To weaving’s progenitor, he brought a refined if irreverent inventiveness, framing radical non-conformity within an anthropologist’s disciplinary understanding.

Albers’ commitment to making artwork proceeded throughout her career in tandem with her dedication to designing for industrial fabrication. A scant five years after publishing On Weaving, she had given up her looms. Now concentrating in earnest on printmaking, she employed others’ hands to execute designs for large scale woven forms (as seen in the two versions of Vicara Rug, 1959), and to remake her lost Bauhaus wall-hangings. Albers considered these “portable murals,” for her the art form of the future, ideally suited to the fast-paced nomadic character of modern life. In 1967 she responded to a commission for the lobby of the Camino Real Hotel in Mexico City by reprising the composition featured in the Vicara Rugs—a modular design based on the repeated motif of a triangle, a bifurcated square—and again reworked it in 1969, this time as a screenprint. With roots in Peruvian textile arts and pre-Columbian Mexican architecture, this grid-based design continued to mutate over more than a decade resulting in a range of exceptional prints and some of her most sought-after furnishing fabrics. Waiving her former commitment to hands-on experimentation in favor of collaboration with knowledgeable technicians, Albers embraced mechanistic processes with adroit resourcefulness. Reversing, rotating, superimposing and displacing the registration of plates, favoring screen-printing and photo-offset for their hard-edge exactitude, her mature graphic works eschew illusory pictorialism and personalized gesture. Mountainous I–VI, 1978, arguably a highpoint in this remarkable display of experimentation within limits, testifies to her trust in dynamic partnerships with professional counterparts. As inkless intaglio impressions, the six prints in the series depend on the play of light over subtly textured surfaces to make visible their design. Tellingly, a tactile apprehension, made by exploratory fingers sensitive to the nuanced interplay of geometric planar surfaces, could be equally revealing. In the mid-’70s, when woven versions of her design, Eclat, c. 1974, proved impossible to realize to an acceptable standard, Albers agreed, in an unprecedented move, to its fabrication in the form of printed cloth.

In the series of interrelated works beginning with Vicara Rug and extending, through Mountainous I–VI, into the ‘80s with the silkscreen, Letter, Albers stepped back, literally and figuratively, by prioritizing the interface of materials and apparatus. In 1947 she had written, “Not only the materials themselves which we come to know in a craft are our teachers. The tools, or the more mechanized tools, our machines, are our guides too.” Though she was a persuasive apologist for the Modernist textile-designer and -artist, Albers’ legacy is routinely parsed in relation to hand loomed studio craft, which shuns technological invention in its prioritizing of subjective expression. Inimical to tactical operations in which ends are anticipated if not fully preconceived, making in this model evolves from improvisation and experimentation, incremental decisions taken en route in what is essentially an open-ended process. Albers’ later work, announced but not fully limned in On Weaving, positions the hand as the facilitator of the apparatus in acknowledgment that reproducibility and seriality lie at the core of woven form. The works on view in Maneuver by Zoe Leonard, Sarah Charlesworth and Rosemarie Trockel, like others in the exhibition, take their point of departure and reference from woven forms. That said, the strategies these very different artists adopt—their close engagement with the technical apparatus mobilized to realize their conceptions—aligns with Albers’ practice in later work, and so reveals new facets to her legacy.

Key to Trockel’s and Charlesworth’s use of the ubiquitous plaid is its structural and formal embeddedness in grid-based design. Among the earliest of what would come to be known as her “knit paintings,” Trockel’s modestly-scaled untitled works from 1986 were made on an automated industrial knit- ting machine. Cognate with both modernist pictorial abstraction and the rectilinear interlaced structure basic to weaving, plaids are some of the oldest known fabrics, dating back millennia. While among the more fundamental of woven patterns, plaid has, however, no integral relationship to the looping structure of knitted cloth. Neither a “natural” starting point for knitted designs for domestic handicraft nor for automated mass production—a misfit, in short—it’s a perfect signifier for Trockel’s mordant feminist purposes. For a group of four works from the early ’80s, Charlesworth, a Pictures Generations artist, rephotographed photographs of Scottish tartans, then enlarged each print to the point where its emergent dot screen vies with the textile’s interlaced warp and weft. Through the addition of bright strips of translucent gel she transformed the images, with their competing formal logics, into sartorial signifiers: monikers of clan identity.

Habitation is a Habit, Leonard’s contribution to Interiors, 2012, a reader in the Center for Curatorial Studies series Perspectives on Art and Culture, took the form of a response to Anni Albers’ 1957 essay, “The Pliable Plane: Textiles in Architecture.” In place of images of yardage Albers herself had designed, Leonard substituted iPhone photographs of commonplace mass-produced textiles found within her own home. Seven years later, she reconceived that intervention for display in the galleries of the Artist’s Institute. Now printed in color as well as black and white, the five-part reprise shines light on protocols informing—and distinguishing—artworks and illustrations similarly tasked with photographic representation of utilitarian textile designs. As the illustrations in On Weaving evidence, conventions and codes prioritized in the reproduction of woven forms, whether domestic fabric or art-object, was a subject that had long preoccupied Albers.

The term “maneuver” denotes a directed, or planned and controlled, set of decisions; a procedural, coordinated movement designed to gain a tactical end. In its transitive state, “maneuver” implies to guide with adroitness and design; to bring about or secure as a result of skillful management. Etymological investigation highlights origins not only in manus, Latin, meaning “hand,” but also Old French, “made by hand.” While the role of handcraft cannot be ignored, the primary operations determining the artworks featured here can better be understood as maneuvers.

—Lynne Cooke

Lynne Cooke is Senior Curator, Special Projects in Modern Art, National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC. She was the 2018 Foundation To-Life, Inc. Arthur and Carol Kaufman Goldberg Visiting Curator at Hunter College.

The Artist’s Institute at Hunter College and Lynne Cooke thank Carol and Arthur Goldberg, the Estate of Sarah Charlesworth, Paula Cooper Gallery, Alexander Gray Associates, Hauser & Wirth, Longhouse Reserve, the Museum of Art and Design, and the Rubell Family Collection for making this exhibition possible. With additional thanks to the artists, Elissa Auther, Brenda Danilowitz at The Josef and Anni Albers Foundation, Jay Gorney, and Monika Sprüth.

Research for this exhibition was conducted as part of the Foundation To-Life, Inc. Arthur and Carol Kaufman Goldberg Curatorial Workshops at Hunter College. These workshops are designed to bring curators of international stature to the Hunter campus to work with students in the MA program in Art History and the MFA program in Studio Art for

an extended period of time. Participants in the 2018–19 seminar were Evan Bellantone, Kyle Croft, Michelangelo Dipietrantonio, Molly Everett, Mindy Friedman, Anna Lee, Livia Margon, Chris Murtha, Allie Rickard, Anna Schmidt, and Jake Shaikewitz.

18 September – 14 December 2019

Anni Albers

Polly Apfelbaum

Sarah Charlesworth

Zoe Leonard

Ed Rossbach

Rosemarie Trockel

curated by Lynne Cooke

Among the greatest weavers of the past century, Anni Albers today is more often encountered through her texts than her textiles. In 1965 she published On Weaving, a magisterial publication that drew on her deep knowledge of this artform. Neither a tract for specialists nor a how-to book, it was intended for readers far-beyond the world of textile practitioners. Now a classic in its field, On Weaving achieved its broad readership by dint of setting forth in concise lucid prose what Albers deemed the principles of woven form. Though coincident with a protean moment of experimentation in off-loom techniques and volumetric free-standing forms, her stance was unyielding: weaving, one the most ancient crafts, remained “essentially unchanged to this day.” Hand-loom weaving, defined as the making of a pliable plane from a structural grid of rectangularly interlaced threads, was, moreover, unequivocally “modern,” and so could serve modern needs, whether those of industry, craft or art. Its structural framework of interlaced soft fibers is, “also the formative framework: woven forms of whatever sort retain always this horizontal vertical character that goes back to their origin.” On Weaving’s copious illustrations—textiles by the great pre-Columbian weavers of Peru, samples of contemporary drapery and upholstery yardage, and fabric made with related techniques such as twining, knotting, looping and braiding—are supplemented by numerous diagrams, above all, by draft notations. Grid-based graphs that record basic weaving structures, these draft notations, in turn, evoke other forms of abstraction, most obviously abstract painting. For it was the grid, with its formal and structural autonomy, Rosalind Krauss contended, that declared “the modernity of modernist art.”

Grey Scale 1 and 2, 2015, embody Polly Apfelbaum’s fascination with a popular mid-century reference book featuring draft notations of traditional American weaving patterns. Each of her paired wall hangings comprises a checkerboard, every unit of which limns a different abstract design mapped out in ink dots with the aid of a plastic stencil. Randomly running the gamut of the dark/light spectrum, inflected with the accidents of manual application, they contest the conformity implicit in geometric order and standardization.

Apfelbaum’s delight in the decorative and tactile, no less than in the grid’s tolerances, is shared by Ed Rossbach, whose Damask Waterfall, 1977, similarly tests the checkboard’s presumption of strict regularity. For the most part, Rossbach cleaved, as did Albers, to that near-timeless conception of the hand-loomed textile as a rectilinear pliable plane, in opposition to the contemporary vanguard cohort who generated the more freewheeling fiber art movement of the 1960s. Also like Albers, Rossbach was an avid student of techniques and forms from diverse cultures, past and present, which he explored in both his writing and his textile practice. As drawn to forms of experimentation that tested the bounds of normative notions as to the recuperation and preservation of traditional modes, Rossbach engaged a plethora of humble materials in his weavings, as well as in basketry, which he deemed “a textile art” in the title of a seminal publication. To weaving’s progenitor, he brought a refined if irreverent inventiveness, framing radical non-conformity within an anthropologist’s disciplinary understanding.

Albers’ commitment to making artwork proceeded throughout her career in tandem with her dedication to designing for industrial fabrication. A scant five years after publishing On Weaving, she had given up her looms. Now concentrating in earnest on printmaking, she employed others’ hands to execute designs for large scale woven forms (as seen in the two versions of Vicara Rug, 1959), and to remake her lost Bauhaus wall-hangings. Albers considered these “portable murals,” for her the art form of the future, ideally suited to the fast-paced nomadic character of modern life. In 1967 she responded to a commission for the lobby of the Camino Real Hotel in Mexico City by reprising the composition featured in the Vicara Rugs—a modular design based on the repeated motif of a triangle, a bifurcated square—and again reworked it in 1969, this time as a screenprint. With roots in Peruvian textile arts and pre-Columbian Mexican architecture, this grid-based design continued to mutate over more than a decade resulting in a range of exceptional prints and some of her most sought-after furnishing fabrics. Waiving her former commitment to hands-on experimentation in favor of collaboration with knowledgeable technicians, Albers embraced mechanistic processes with adroit resourcefulness. Reversing, rotating, superimposing and displacing the registration of plates, favoring screen-printing and photo-offset for their hard-edge exactitude, her mature graphic works eschew illusory pictorialism and personalized gesture. Mountainous I–VI, 1978, arguably a highpoint in this remarkable display of experimentation within limits, testifies to her trust in dynamic partnerships with professional counterparts. As inkless intaglio impressions, the six prints in the series depend on the play of light over subtly textured surfaces to make visible their design. Tellingly, a tactile apprehension, made by exploratory fingers sensitive to the nuanced interplay of geometric planar surfaces, could be equally revealing. In the mid-’70s, when woven versions of her design, Eclat, c. 1974, proved impossible to realize to an acceptable standard, Albers agreed, in an unprecedented move, to its fabrication in the form of printed cloth.

In the series of interrelated works beginning with Vicara Rug and extending, through Mountainous I–VI, into the ‘80s with the silkscreen, Letter, Albers stepped back, literally and figuratively, by prioritizing the interface of materials and apparatus. In 1947 she had written, “Not only the materials themselves which we come to know in a craft are our teachers. The tools, or the more mechanized tools, our machines, are our guides too.” Though she was a persuasive apologist for the Modernist textile-designer and -artist, Albers’ legacy is routinely parsed in relation to hand loomed studio craft, which shuns technological invention in its prioritizing of subjective expression. Inimical to tactical operations in which ends are anticipated if not fully preconceived, making in this model evolves from improvisation and experimentation, incremental decisions taken en route in what is essentially an open-ended process. Albers’ later work, announced but not fully limned in On Weaving, positions the hand as the facilitator of the apparatus in acknowledgment that reproducibility and seriality lie at the core of woven form. The works on view in Maneuver by Zoe Leonard, Sarah Charlesworth and Rosemarie Trockel, like others in the exhibition, take their point of departure and reference from woven forms. That said, the strategies these very different artists adopt—their close engagement with the technical apparatus mobilized to realize their conceptions—aligns with Albers’ practice in later work, and so reveals new facets to her legacy.

Key to Trockel’s and Charlesworth’s use of the ubiquitous plaid is its structural and formal embeddedness in grid-based design. Among the earliest of what would come to be known as her “knit paintings,” Trockel’s modestly-scaled untitled works from 1986 were made on an automated industrial knit- ting machine. Cognate with both modernist pictorial abstraction and the rectilinear interlaced structure basic to weaving, plaids are some of the oldest known fabrics, dating back millennia. While among the more fundamental of woven patterns, plaid has, however, no integral relationship to the looping structure of knitted cloth. Neither a “natural” starting point for knitted designs for domestic handicraft nor for automated mass production—a misfit, in short—it’s a perfect signifier for Trockel’s mordant feminist purposes. For a group of four works from the early ’80s, Charlesworth, a Pictures Generations artist, rephotographed photographs of Scottish tartans, then enlarged each print to the point where its emergent dot screen vies with the textile’s interlaced warp and weft. Through the addition of bright strips of translucent gel she transformed the images, with their competing formal logics, into sartorial signifiers: monikers of clan identity.

Habitation is a Habit, Leonard’s contribution to Interiors, 2012, a reader in the Center for Curatorial Studies series Perspectives on Art and Culture, took the form of a response to Anni Albers’ 1957 essay, “The Pliable Plane: Textiles in Architecture.” In place of images of yardage Albers herself had designed, Leonard substituted iPhone photographs of commonplace mass-produced textiles found within her own home. Seven years later, she reconceived that intervention for display in the galleries of the Artist’s Institute. Now printed in color as well as black and white, the five-part reprise shines light on protocols informing—and distinguishing—artworks and illustrations similarly tasked with photographic representation of utilitarian textile designs. As the illustrations in On Weaving evidence, conventions and codes prioritized in the reproduction of woven forms, whether domestic fabric or art-object, was a subject that had long preoccupied Albers.

The term “maneuver” denotes a directed, or planned and controlled, set of decisions; a procedural, coordinated movement designed to gain a tactical end. In its transitive state, “maneuver” implies to guide with adroitness and design; to bring about or secure as a result of skillful management. Etymological investigation highlights origins not only in manus, Latin, meaning “hand,” but also Old French, “made by hand.” While the role of handcraft cannot be ignored, the primary operations determining the artworks featured here can better be understood as maneuvers.

—Lynne Cooke

Lynne Cooke is Senior Curator, Special Projects in Modern Art, National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC. She was the 2018 Foundation To-Life, Inc. Arthur and Carol Kaufman Goldberg Visiting Curator at Hunter College.

The Artist’s Institute at Hunter College and Lynne Cooke thank Carol and Arthur Goldberg, the Estate of Sarah Charlesworth, Paula Cooper Gallery, Alexander Gray Associates, Hauser & Wirth, Longhouse Reserve, the Museum of Art and Design, and the Rubell Family Collection for making this exhibition possible. With additional thanks to the artists, Elissa Auther, Brenda Danilowitz at The Josef and Anni Albers Foundation, Jay Gorney, and Monika Sprüth.

Research for this exhibition was conducted as part of the Foundation To-Life, Inc. Arthur and Carol Kaufman Goldberg Curatorial Workshops at Hunter College. These workshops are designed to bring curators of international stature to the Hunter campus to work with students in the MA program in Art History and the MFA program in Studio Art for

an extended period of time. Participants in the 2018–19 seminar were Evan Bellantone, Kyle Croft, Michelangelo Dipietrantonio, Molly Everett, Mindy Friedman, Anna Lee, Livia Margon, Chris Murtha, Allie Rickard, Anna Schmidt, and Jake Shaikewitz.