Americana: Virginia

08 - 19 Nov 2011

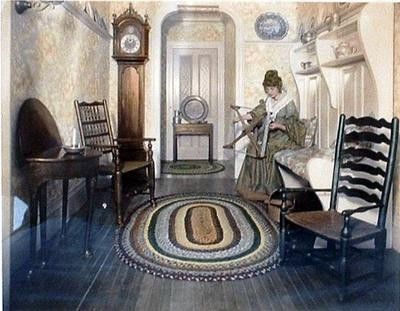

Photo produced inside Nutting's Massachusettes home, advertised for sale in Nutting's 1915 Expansible Sales catalog, Copyright www.WallaceNuttingLibrary.com

AMERICANA: VIRGINIA

The Reproductions Program

8 - 19 November, 2011

To reproduce something is to make a copy, a replica of the original. A reproduction affords the possibility of investing in a romanticized ideal from the past. An exemplary instance from American history is provided by Colonial Williamsburg and The Reproductions Program —both of which evoke and commodify the values of an earlier era. The American Colonial is a type of design that brings together [is this a type of house, or generic design term, or place?], European influences with historically available materials from the land [which land?] and the original colonies of New England. This hybrid seeks to represent the ingenious and pioneering spirit of Early America.

Colonial Williamsburg was a large-scale preservation project, a collaboration between the reverend W.A.R. Goodwin and John D. Rockefeller Jr. in the early 20th century, that aimed to create a model of an idyllic American town. Goodwin enlisted the financial support of Rockefeller to systematically purchase properties in Williamsburg—eventually restoring the entire town to its former glory as the second capital of Virginia. This restoration and reconstruction project resulted in what is now known as Colonial Williamsburg, a “living museum” that evokes the real town, where Thomas Jefferson and George Washington walked the streets and where the formation of early American policy, society, and religion was established. The Reproduction Program is a marketplace in Williamsburg that offers reproductions of the design objects seen in the original buildings. These objects are branded with a hallmark, ensuring a historical authenticity, and are now marketed through catalogs, outside vendors, and websites. These marketing techniques offer a sense of history tied into the product, as well as a way to distribute the Colonial aesthetic far and wide, within many different price-points. For example, the book of Williamsburg paint colors offers the possibility of painting your walls in “the lusty hues that stirred a nation.” Today, as Bill Bryson writes, Williamsburg is a, “sort of Disney World of American History.” Operating as both a theme-park and a showroom for historical education and consumption, the restoration of Colonial Williamsburg was conceived as an educational [repetition on education here] and preservationist endeavor. The success of this strategy is apparent as the American Colonial aesthetic still holds a place in many homes across the country.

A similar, and earlier, example of the commercial gain from Colonial nostalgia can be seen in the endeavors of Wallace Nutting, a congressional minister and shrewd businessman, who made it his mission to reestablish a moral order by creating his own industry of reproduction furniture. Nutting purchased deteriorating Colonial estates, filled them with reproduction furniture of his own design and staged photographs. These photographs (hand tinted affordable art objects) were marketed and sold, but were also used as advertisements for the furnishings he manufactured. By 1915, Nutting had published a catalog, selling a reinvention of what he referred to as “Old America.” He strove to produce affordable goods that would find their ways into modern American homes, taking a commercial and domestic approach to enforcing traditional colonial values back into the daily lives of the people. Considered the Martha Stuart of his time, Nutting’s products were extremely popular and his business, Wallace Nutting Incorporated, was a financial success. He not only attempted to establish a moral nostalgia, but also to commoditize it.

The exhibition, The Reproductions Program brings together a combination of these decorative items as a reflection of the effects of the Reproductions Program’s commoditization and dispersal of Colonial nostalgia and history at large into the American interiors of today.

Stephanie Kern

The Reproductions Program

8 - 19 November, 2011

To reproduce something is to make a copy, a replica of the original. A reproduction affords the possibility of investing in a romanticized ideal from the past. An exemplary instance from American history is provided by Colonial Williamsburg and The Reproductions Program —both of which evoke and commodify the values of an earlier era. The American Colonial is a type of design that brings together [is this a type of house, or generic design term, or place?], European influences with historically available materials from the land [which land?] and the original colonies of New England. This hybrid seeks to represent the ingenious and pioneering spirit of Early America.

Colonial Williamsburg was a large-scale preservation project, a collaboration between the reverend W.A.R. Goodwin and John D. Rockefeller Jr. in the early 20th century, that aimed to create a model of an idyllic American town. Goodwin enlisted the financial support of Rockefeller to systematically purchase properties in Williamsburg—eventually restoring the entire town to its former glory as the second capital of Virginia. This restoration and reconstruction project resulted in what is now known as Colonial Williamsburg, a “living museum” that evokes the real town, where Thomas Jefferson and George Washington walked the streets and where the formation of early American policy, society, and religion was established. The Reproduction Program is a marketplace in Williamsburg that offers reproductions of the design objects seen in the original buildings. These objects are branded with a hallmark, ensuring a historical authenticity, and are now marketed through catalogs, outside vendors, and websites. These marketing techniques offer a sense of history tied into the product, as well as a way to distribute the Colonial aesthetic far and wide, within many different price-points. For example, the book of Williamsburg paint colors offers the possibility of painting your walls in “the lusty hues that stirred a nation.” Today, as Bill Bryson writes, Williamsburg is a, “sort of Disney World of American History.” Operating as both a theme-park and a showroom for historical education and consumption, the restoration of Colonial Williamsburg was conceived as an educational [repetition on education here] and preservationist endeavor. The success of this strategy is apparent as the American Colonial aesthetic still holds a place in many homes across the country.

A similar, and earlier, example of the commercial gain from Colonial nostalgia can be seen in the endeavors of Wallace Nutting, a congressional minister and shrewd businessman, who made it his mission to reestablish a moral order by creating his own industry of reproduction furniture. Nutting purchased deteriorating Colonial estates, filled them with reproduction furniture of his own design and staged photographs. These photographs (hand tinted affordable art objects) were marketed and sold, but were also used as advertisements for the furnishings he manufactured. By 1915, Nutting had published a catalog, selling a reinvention of what he referred to as “Old America.” He strove to produce affordable goods that would find their ways into modern American homes, taking a commercial and domestic approach to enforcing traditional colonial values back into the daily lives of the people. Considered the Martha Stuart of his time, Nutting’s products were extremely popular and his business, Wallace Nutting Incorporated, was a financial success. He not only attempted to establish a moral nostalgia, but also to commoditize it.

The exhibition, The Reproductions Program brings together a combination of these decorative items as a reflection of the effects of the Reproductions Program’s commoditization and dispersal of Colonial nostalgia and history at large into the American interiors of today.

Stephanie Kern