There's No Place Like Home

20 Apr - 23 Jun 2013

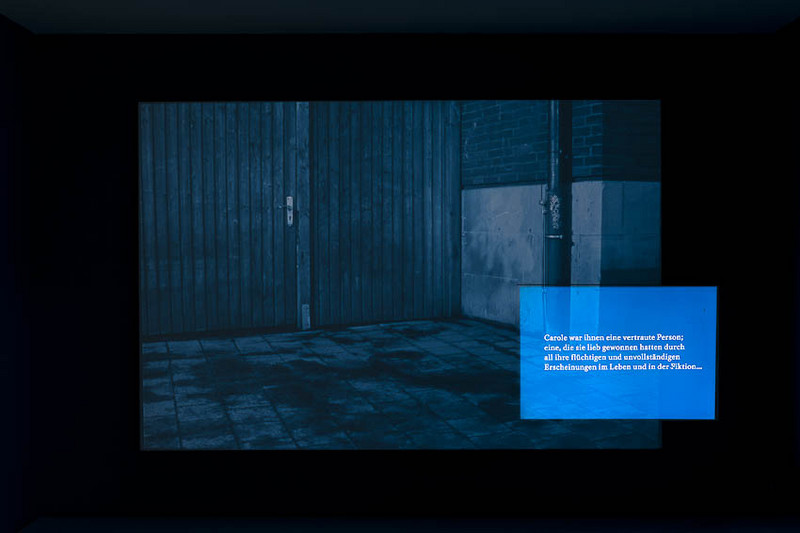

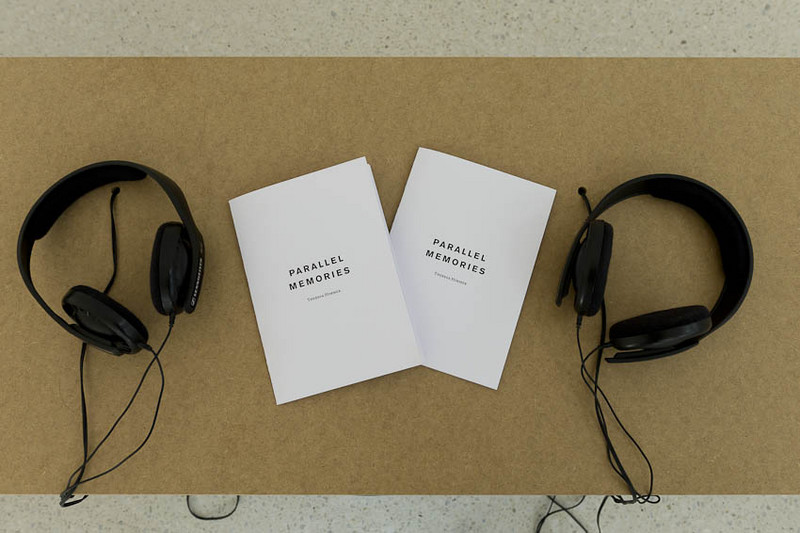

Theresa Himmer, Parallel Memories, 2013

Installation view at Westfälischer Kunstverein. Photo: Thorsten Arendt

Installation view at Westfälischer Kunstverein. Photo: Thorsten Arendt

Nanna Debois Buhl, Night Map II, 2013

Installation view at Westfälischer Kunstverein. Photo: Thorsten Arendt

Installation view at Westfälischer Kunstverein. Photo: Thorsten Arendt

Nanna Debois Buhl, Night Map II, 2013

Installation view at Westfälischer Kunstverein. Photo: Thorsten Arendt

Installation view at Westfälischer Kunstverein. Photo: Thorsten Arendt

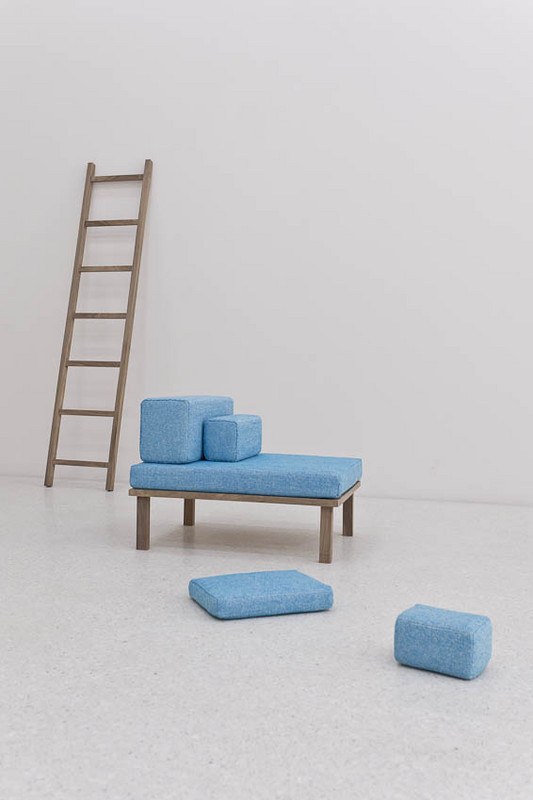

Jean-Pascal Flavien, breathing house, sequence or phrase (5), 2013

Installation view at Westfälischer Kunstverein. Photo: Thorsten Arendt

Courtesy: Catherine Bastide

Installation view at Westfälischer Kunstverein. Photo: Thorsten Arendt

Courtesy: Catherine Bastide

Jean-Pascal Flavien, breathing house, sequence or phrase (5), 2013

Installation view at Westfälischer Kunstverein. Photo: Thorsten Arendt

Courtesy: Catherine Bastide

Installation view at Westfälischer Kunstverein. Photo: Thorsten Arendt

Courtesy: Catherine Bastide

Theresa Himmer, Parallel Memories, 2013

Installation view at Westfälischer Kunstverein. Photo: Thorsten Arendt

Installation view at Westfälischer Kunstverein. Photo: Thorsten Arendt

Theresa Himmer, Parallel Memories, 2013

Installation view at Westfälischer Kunstverein. Photo: Thorsten Arendt

Installation view at Westfälischer Kunstverein. Photo: Thorsten Arendt

Theresa Himmer, Parallel Memories, 2013

Installation view at Westfälischer Kunstverein. Photo: Thorsten Arendt

Installation view at Westfälischer Kunstverein. Photo: Thorsten Arendt

Theresa Himmer, Parallel Memories, 2013

Installation view at Westfälischer Kunstverein. Photo: Thorsten Arendt

Installation view at Westfälischer Kunstverein. Photo: Thorsten Arendt

Theresa Himmer, Parallel Memories, 2013

Installation view at Westfälischer Kunstverein. Photo: Thorsten Arendt

Installation view at Westfälischer Kunstverein. Photo: Thorsten Arendt

THERE'S NO PLACE LIKE HOME

20 April - 23 June 2013

Eric Baudelaire, Nanna Debois Buhl, Jean-Pascal Flavien, Theresa Himmer, Maria Loboda, Benjamin Tiven, Jeronimo Voss, Christoph Westermeier

Curator: Kristina Scepanski

“Building Dwelling Thinking” – Martin Heidegger chose this list of activities as the title for a lecture held at the Darmstadt Symposium in 1951, and it would seem that the lack of punctuation was quite deliberate. It simultaneously conveys both a consecutive sequence and reciprocal concurrency. The three activities are more closely linked than merely in terms of the implicit chronology, in which one must necessarily happen before the other. Instead, the concepts seem to depend upon one another. The core of Heidegger’s presentation was the separation of dwelling from the pure sense of having accommodation. He emphasised the existential dimension of dwelling as a basic facet of human existence. As a consequence, building itself is more than just architectural construction: we create things and places that structure and accommodate our actions and behaviour. Concomitantly, they develop relationships, both among themselves and to the environment, opening up spaces for living and being in the world.

The construction of a new residential space in a Heideggerian sense is one of the aims of “There’s no place like home” – the Westfälischer Kunstverein’s first exhibition in its new venue on Rothenburg. After a somewhat itinerant programme based at various venues across the city over the past four years, the Kunstverein now faces the challenge and unique opportunity of appropriating a new site and duly cultivating it as a space for living and thinking according to its own designs. Understandably, this process of moving in takes time, and so the Kunstverein and the artworks themselves gradually took phased possession of the new space. The newly installed works were presented on three nights before the opening as part of a series of artist talks. In this way, the exhibition has gradually expanded and provokes a different perception of space on a daily basis.

The relationship between people and space, theorised not only by Heidegger, accrues great importance because it has always shaped the self-awareness and understanding of individual identity. One of the many different relationships between people and space is that which we commonly call ‘home’. The concept of home can no more be reduced to geographical or physical environments than can Heidegger’s idea of a space for dwelling. Home refers to something with which the individual can identify – indeed, even abstractions can represent a spiritual home.

With its title “There’s no place like home”, the exhibition deliberately departs from that inherently German concept of Heimat. The intention here is precisely not to create a sentimental assessment of a given place or situation, but conversely, to reveal the diversity in the idea of a sense of belonging to a place. Eight international artists launch a critical appraisal of the concept home, questioning its appropriateness for the time and furthermore, to speculate upon the different types of relationships between people and places. In so doing, the title flirts stylistically with this feeling of home which is mostly defined in terms of nationality or region, while at the same time literally denying this very fixedness: There is NO place like home.

The individual works in the exhibition address different aspects, consequences and potentials that arise from the nexus of ideas surrounding home, Heimat and belonging. Theresa Himmer examines her individual childhood memories of a place, which, due to specific political circumstances and when compared to her contemporaries, has etched itself into her identity in quite different ways. It becomes apparent that meaning is only assigned to places by individuals. Nanna Debois Buhl’s slide installation describes the reverse influence of a locality or an urban structure on an individual’s emotions. Jean-Pascal Flavien examines how a very specific architectural home can influence our actions and thinking, with the suggestion that we might perceive dwelling as a creative activity. By means of her work’s vivid illustration of the process of appropriating a specific site via personal belongings, Maria Loboda’s inherently moveable work continues the approach of the changing perception of space contained in the prologue to the exhibition. Christoph Westermeier has developed a work specifically for the Kunstverein that investigates the Association’s geographical, historical and cultural roots on the basis of its art collection. Benjamin Tiven’s project for the Kunstverein’s website also processes the Association’s local and temporal position via a system for the design of cultural monuments. Jeronimo Voss’ installation and Eric Baudelaire’s film postulate the notion that homelessness and abandonment of home do not necessarily have to be categorised as negative experiences, but can instead generate productive potential.

By investigating a much more individual type of situatedness in the world that transcends notions of home and homeland, the artistic positions in “There’s no place like home” effectively question the productivity of concepts that fix us to a specific location.

However, the secret protagonist of this exhibition is none other than the Kunstverein itself. Besides the appropriation and cultivation of new thinking and dwelling space described at the outset – which the first exhibition in the new building intends to achieve – “There’s no place like home” should also be understood as a diagnosis of Westfälischer Kunstverein’s duties, responsibilities and self-understanding. In what way does the Kunstverein relate to its origins? To what extent is its identity shaped by its immediate environment, and how can and should it be effective as a site? “There’s no place like home” also implicitly provides a kind of assessment of the Institution ‘Kunstverein’s’ overall position, which, however, should not be viewed literally, i.e. nationally or geographically any more than the concepts of Heimat or home. The order of the day must now be to maintain the productivity stemming from its previous, quite literal homelessness despite its new, fixed location.

20 April - 23 June 2013

Eric Baudelaire, Nanna Debois Buhl, Jean-Pascal Flavien, Theresa Himmer, Maria Loboda, Benjamin Tiven, Jeronimo Voss, Christoph Westermeier

Curator: Kristina Scepanski

“Building Dwelling Thinking” – Martin Heidegger chose this list of activities as the title for a lecture held at the Darmstadt Symposium in 1951, and it would seem that the lack of punctuation was quite deliberate. It simultaneously conveys both a consecutive sequence and reciprocal concurrency. The three activities are more closely linked than merely in terms of the implicit chronology, in which one must necessarily happen before the other. Instead, the concepts seem to depend upon one another. The core of Heidegger’s presentation was the separation of dwelling from the pure sense of having accommodation. He emphasised the existential dimension of dwelling as a basic facet of human existence. As a consequence, building itself is more than just architectural construction: we create things and places that structure and accommodate our actions and behaviour. Concomitantly, they develop relationships, both among themselves and to the environment, opening up spaces for living and being in the world.

The construction of a new residential space in a Heideggerian sense is one of the aims of “There’s no place like home” – the Westfälischer Kunstverein’s first exhibition in its new venue on Rothenburg. After a somewhat itinerant programme based at various venues across the city over the past four years, the Kunstverein now faces the challenge and unique opportunity of appropriating a new site and duly cultivating it as a space for living and thinking according to its own designs. Understandably, this process of moving in takes time, and so the Kunstverein and the artworks themselves gradually took phased possession of the new space. The newly installed works were presented on three nights before the opening as part of a series of artist talks. In this way, the exhibition has gradually expanded and provokes a different perception of space on a daily basis.

The relationship between people and space, theorised not only by Heidegger, accrues great importance because it has always shaped the self-awareness and understanding of individual identity. One of the many different relationships between people and space is that which we commonly call ‘home’. The concept of home can no more be reduced to geographical or physical environments than can Heidegger’s idea of a space for dwelling. Home refers to something with which the individual can identify – indeed, even abstractions can represent a spiritual home.

With its title “There’s no place like home”, the exhibition deliberately departs from that inherently German concept of Heimat. The intention here is precisely not to create a sentimental assessment of a given place or situation, but conversely, to reveal the diversity in the idea of a sense of belonging to a place. Eight international artists launch a critical appraisal of the concept home, questioning its appropriateness for the time and furthermore, to speculate upon the different types of relationships between people and places. In so doing, the title flirts stylistically with this feeling of home which is mostly defined in terms of nationality or region, while at the same time literally denying this very fixedness: There is NO place like home.

The individual works in the exhibition address different aspects, consequences and potentials that arise from the nexus of ideas surrounding home, Heimat and belonging. Theresa Himmer examines her individual childhood memories of a place, which, due to specific political circumstances and when compared to her contemporaries, has etched itself into her identity in quite different ways. It becomes apparent that meaning is only assigned to places by individuals. Nanna Debois Buhl’s slide installation describes the reverse influence of a locality or an urban structure on an individual’s emotions. Jean-Pascal Flavien examines how a very specific architectural home can influence our actions and thinking, with the suggestion that we might perceive dwelling as a creative activity. By means of her work’s vivid illustration of the process of appropriating a specific site via personal belongings, Maria Loboda’s inherently moveable work continues the approach of the changing perception of space contained in the prologue to the exhibition. Christoph Westermeier has developed a work specifically for the Kunstverein that investigates the Association’s geographical, historical and cultural roots on the basis of its art collection. Benjamin Tiven’s project for the Kunstverein’s website also processes the Association’s local and temporal position via a system for the design of cultural monuments. Jeronimo Voss’ installation and Eric Baudelaire’s film postulate the notion that homelessness and abandonment of home do not necessarily have to be categorised as negative experiences, but can instead generate productive potential.

By investigating a much more individual type of situatedness in the world that transcends notions of home and homeland, the artistic positions in “There’s no place like home” effectively question the productivity of concepts that fix us to a specific location.

However, the secret protagonist of this exhibition is none other than the Kunstverein itself. Besides the appropriation and cultivation of new thinking and dwelling space described at the outset – which the first exhibition in the new building intends to achieve – “There’s no place like home” should also be understood as a diagnosis of Westfälischer Kunstverein’s duties, responsibilities and self-understanding. In what way does the Kunstverein relate to its origins? To what extent is its identity shaped by its immediate environment, and how can and should it be effective as a site? “There’s no place like home” also implicitly provides a kind of assessment of the Institution ‘Kunstverein’s’ overall position, which, however, should not be viewed literally, i.e. nationally or geographically any more than the concepts of Heimat or home. The order of the day must now be to maintain the productivity stemming from its previous, quite literal homelessness despite its new, fixed location.