Rhoda Kellogg

17 Jan - 09 Mar 2019

RHODA KELLOGG

organized by Brian Belott

17 January - 9 March 2019

White Columns is pleased to present the first ever exhibition of the work of Rhoda Kellogg (1898-1987.) The exhibition has been organized by the New York-based artist Brian Belott, a long-standing champion of Kellogg’s work.

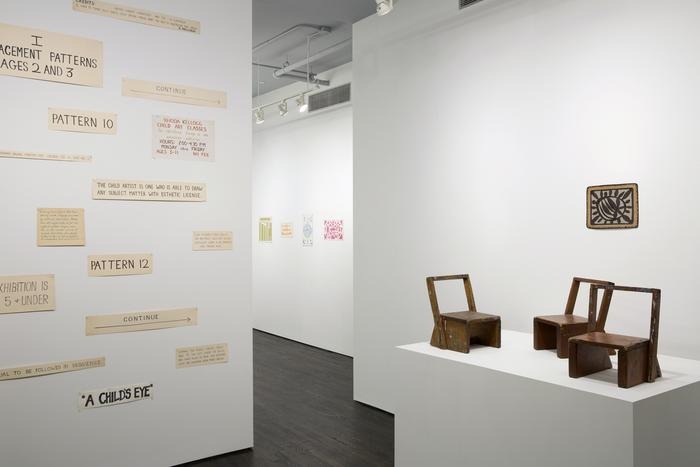

Rhoda Kellogg was a psychologist and early-childhood educator and the director of the Phoebe A. Hearst Preschool Learning Center (which was a part of the Golden Gate Kindergarten Association, in San Francisco) for nearly three decades. Over the course of her lifetime Kellogg amassed a collection of more than two million drawings by children between the ages of two and eight. In 2017 Belott staged ‘Dr. Kid President Jr.’ at Gavin Brown’s enterprise in Harlem: an expansive installation that juxtaposed his own work alongside drawings from Kellogg’s collection of children’s art. Kellogg’s own work – produced during the last decade of her life, when she was in her 70s and 80s – has never been exhibited before. The exhibition at White Columns comprises two groups of her works on paper: cut-paper collages and mixed-media drawings, alongside Kellogg’s designs for children’s furniture and a selection of her hand-written exhibition signage.

Writing about the project and his interest in Kellogg’s work Belott has said that:

“Rhoda Kellogg (1898-1987) is an American hero who dedicated her life to a field of study that remains severely underappreciated some forty years later: early childhood art. Kellogg showed the highest regard for an age group who normally are the first to be ushered off a sinking boat, but once upon dry land are the first to be shuffled out of sight, out of the way so that the adult world can continue with its own agenda. Not only was caring for very young children considered to be unskilled “women’s work,” children’s abstract scribbles were the least concerning aspect of their development. I believe it is because Rhoda invested in this particularly undervalued field that her life's efforts have been culturally put in a deep freeze.

It is a timely event that Rhoda Kellogg's archive is being exhumed and re-examined. She fought discrimination across age, gender and culture from the time she was a teenager. When Kellogg was a student at university, she was passionately involved in the Suffragette movement. In the spring of 1919, joined by a group of Suffragettes, she picketed the White House and was consequently jailed. While incarcerated, she pushed the envelope further, leading a five-day hunger strike that impelled authorities to release the women. This would be one of many times throughout her life she would appeal to lawmakers for social change.

With a degree in social work, Rhoda focused her attention on early development when she became a parent. Her inability to find quality educational experiences for her daughter led her to participate in the establishment of the first nursery schools in San Francisco to serve children under three. From there, she supervised and taught in multiple preschool learning centers in the Bay Area. It was in this context that she observed the early “aesthetic urges” and patterns of movement - and so ignited the fire that became the largest study of scribbles and finger paintings ever conducted. Like a scientist who, while studying the arc of a grasshopper's hop, accidentally stumbles upon the exact distances between planets, Rhoda enters the storm of the scribbles. A nonsensical hairball in the adult bathtub, she realizes a bubble-bath in the Gestalts of visual perception. To be clear, 99% of all early child art (scribblings and finger paintings) is destined for the garbage can - period. In our time and certainly in Kellogg's time, this art is viewed as meaningless garbage. But like a true trailblazer, Kellogg walked into and over the void. She came out the other side with a key of 20 basic scribbles that are made by young artists worldwide, without any prodding by or input from adults. These basic markings are combined repeatedly and follow a distinct evolution toward pictorialism.

Many books that purport to analyze children's art as a measure of intelligence or psychology are in fact based on small samplings, and are often request drawings, which do not spring from the child's own artistic, free explorations. Kellogg asserted that authentic conclusions could not be reached through such limited methodology. As she continued to write and lecture and travel, she found contemporaries in Carl Jung, Rudolf Arnheim, Sir Herbert Read and John Berger. Through the lens of visual learning, she partnered with specialists in multiple disciplines, from dance to neuroscience to pediatrics. These collaborations served to both underscore and expand on her theories. They reinforced that the visuo-mental processes of free scribbling and drawing directly correlate to the healthy development of language, literacy, early math and science concepts, motor coordination and self-esteem.

What amazes me is the zone of confusion child art has always occupied. It is worthless, yet priceless. The contemporary art world cannot figure out how to commodify it, yet it is the source of all art and language. It has been proven to be a central inspiration for some of art history’s top modernists, but it is worth nothing when a four-year-old does similar work with equal competence.

For the past two years, I have had the good fortune to explore the immensity of the Rhoda Kellogg archive. It was like uncovering a laboratory of a mad scientist mashed-up with Mr. Rogers. Within the collection of child art, I discovered a never-before-shown set of paper collages and drawings made by Rhoda herself. Many of these works are dated in the 1980’s, during the last decade of Rhoda’s life.

This exhibition's main focus will be on these elegant paper collages that I believe to be her very last works. What I sense is a closing of a circle of life: Rhoda states that her greatest contribution to the study of children's art is what she termed "implied shape" and "placement patterns." These were the terms and methods she used to understand what others thought was gobbledygook. Though it may be tempting to look at these collages in terms of art history with the likes of Mondrian or Ellsworth Kelly, I think Rhoda is returning to what she first observed in the nursery schools - the wonder of innate creative force bubbling up in the playground of the piece of paper and through implied shape and placement buffets. These are what directed her last works - the beginning and the end - beginning. Hello. “ - Brian Belott

White Columns would like to sincerely thank Brian Belott, the Rhoda Kellogg Archive, and the Golden Gate Kindergarten Association for their enthusiasm and support of this project.

organized by Brian Belott

17 January - 9 March 2019

White Columns is pleased to present the first ever exhibition of the work of Rhoda Kellogg (1898-1987.) The exhibition has been organized by the New York-based artist Brian Belott, a long-standing champion of Kellogg’s work.

Rhoda Kellogg was a psychologist and early-childhood educator and the director of the Phoebe A. Hearst Preschool Learning Center (which was a part of the Golden Gate Kindergarten Association, in San Francisco) for nearly three decades. Over the course of her lifetime Kellogg amassed a collection of more than two million drawings by children between the ages of two and eight. In 2017 Belott staged ‘Dr. Kid President Jr.’ at Gavin Brown’s enterprise in Harlem: an expansive installation that juxtaposed his own work alongside drawings from Kellogg’s collection of children’s art. Kellogg’s own work – produced during the last decade of her life, when she was in her 70s and 80s – has never been exhibited before. The exhibition at White Columns comprises two groups of her works on paper: cut-paper collages and mixed-media drawings, alongside Kellogg’s designs for children’s furniture and a selection of her hand-written exhibition signage.

Writing about the project and his interest in Kellogg’s work Belott has said that:

“Rhoda Kellogg (1898-1987) is an American hero who dedicated her life to a field of study that remains severely underappreciated some forty years later: early childhood art. Kellogg showed the highest regard for an age group who normally are the first to be ushered off a sinking boat, but once upon dry land are the first to be shuffled out of sight, out of the way so that the adult world can continue with its own agenda. Not only was caring for very young children considered to be unskilled “women’s work,” children’s abstract scribbles were the least concerning aspect of their development. I believe it is because Rhoda invested in this particularly undervalued field that her life's efforts have been culturally put in a deep freeze.

It is a timely event that Rhoda Kellogg's archive is being exhumed and re-examined. She fought discrimination across age, gender and culture from the time she was a teenager. When Kellogg was a student at university, she was passionately involved in the Suffragette movement. In the spring of 1919, joined by a group of Suffragettes, she picketed the White House and was consequently jailed. While incarcerated, she pushed the envelope further, leading a five-day hunger strike that impelled authorities to release the women. This would be one of many times throughout her life she would appeal to lawmakers for social change.

With a degree in social work, Rhoda focused her attention on early development when she became a parent. Her inability to find quality educational experiences for her daughter led her to participate in the establishment of the first nursery schools in San Francisco to serve children under three. From there, she supervised and taught in multiple preschool learning centers in the Bay Area. It was in this context that she observed the early “aesthetic urges” and patterns of movement - and so ignited the fire that became the largest study of scribbles and finger paintings ever conducted. Like a scientist who, while studying the arc of a grasshopper's hop, accidentally stumbles upon the exact distances between planets, Rhoda enters the storm of the scribbles. A nonsensical hairball in the adult bathtub, she realizes a bubble-bath in the Gestalts of visual perception. To be clear, 99% of all early child art (scribblings and finger paintings) is destined for the garbage can - period. In our time and certainly in Kellogg's time, this art is viewed as meaningless garbage. But like a true trailblazer, Kellogg walked into and over the void. She came out the other side with a key of 20 basic scribbles that are made by young artists worldwide, without any prodding by or input from adults. These basic markings are combined repeatedly and follow a distinct evolution toward pictorialism.

Many books that purport to analyze children's art as a measure of intelligence or psychology are in fact based on small samplings, and are often request drawings, which do not spring from the child's own artistic, free explorations. Kellogg asserted that authentic conclusions could not be reached through such limited methodology. As she continued to write and lecture and travel, she found contemporaries in Carl Jung, Rudolf Arnheim, Sir Herbert Read and John Berger. Through the lens of visual learning, she partnered with specialists in multiple disciplines, from dance to neuroscience to pediatrics. These collaborations served to both underscore and expand on her theories. They reinforced that the visuo-mental processes of free scribbling and drawing directly correlate to the healthy development of language, literacy, early math and science concepts, motor coordination and self-esteem.

What amazes me is the zone of confusion child art has always occupied. It is worthless, yet priceless. The contemporary art world cannot figure out how to commodify it, yet it is the source of all art and language. It has been proven to be a central inspiration for some of art history’s top modernists, but it is worth nothing when a four-year-old does similar work with equal competence.

For the past two years, I have had the good fortune to explore the immensity of the Rhoda Kellogg archive. It was like uncovering a laboratory of a mad scientist mashed-up with Mr. Rogers. Within the collection of child art, I discovered a never-before-shown set of paper collages and drawings made by Rhoda herself. Many of these works are dated in the 1980’s, during the last decade of Rhoda’s life.

This exhibition's main focus will be on these elegant paper collages that I believe to be her very last works. What I sense is a closing of a circle of life: Rhoda states that her greatest contribution to the study of children's art is what she termed "implied shape" and "placement patterns." These were the terms and methods she used to understand what others thought was gobbledygook. Though it may be tempting to look at these collages in terms of art history with the likes of Mondrian or Ellsworth Kelly, I think Rhoda is returning to what she first observed in the nursery schools - the wonder of innate creative force bubbling up in the playground of the piece of paper and through implied shape and placement buffets. These are what directed her last works - the beginning and the end - beginning. Hello. “ - Brian Belott

White Columns would like to sincerely thank Brian Belott, the Rhoda Kellogg Archive, and the Golden Gate Kindergarten Association for their enthusiasm and support of this project.