Marc Quinn

04 Mar - 09 Apr 2005

White Cube is pleased to present an exhibition of new works by British artist Marc Quinn. Quinn will present a body of work that explores our distanced relationship with our physical selves through the culturally constructed notion of the 'natural' and its hold on the contemporary psyche.

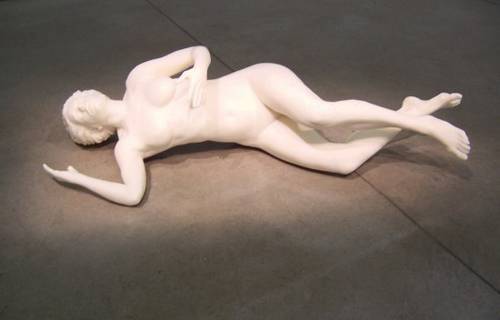

Chemical Life Support includes several compelling figurative sculptures of people who keep chronic illness at bay with drugs. Each sculpture is cast from polymer wax mixed with the drug that keeps each subject alive. The reclining individual figures are positioned as if at zero gravity, conceived so that they barely touch the plinths on which they are set. Innoscience, 2004, is a figure of Quinn's own baby son, Lucas, who suffers from a milk allergy; thus the wax has been mixed with the chemically produced milk-free substitute that has been used to sustain him. For the figure of Silvia Petretti, who is HIV positive, the casting wax has been mixed with her required anti-viral drug. Transplant survivor Carl Whittaker's wax mould contains the drug cocktail that keeps his body from rejecting its own organs. To the viewer, these serene bodies seem healthy and whole; only the titles hint at the secret that is contained within their very substance of lives that are precarious and fragile.

Quinn's new sculptures develop key ideas that can be traced through his earlier work, such as the 'Eternal Spring' installations where he preserved flowers in their most perfect bloom by plunging them into sub-zero silicone tanks and kept them alive by virtue of 'umbilical' electrical cords. In 'The Complete Marbles', figures of people who had lost limbs or were born without them were carved in marble in the classical manner as a way of re-reading the aspirations of Greek and Roman statuary and their reliance on a perceived, imagined and idealised whole. In this current exhibition, Quinn presents two marble heads of a blind man and woman, which appear like any other 'blind' classical sculpture. In this case, Quinn has made the blank stone eyes of classical sculpture (which were, of course, once vividly painted) equivalent with the literal limitations of human perception.

The sculptures Cybernetically Engineered, Cloned and Grown Rabbits recall Quinn's earlier work with DNA, including the portrait of Sir John Sulston, now on show at the National Portrait Gallery. These perfect replicas of disembowelled rabbits are, literally, clones that have been rescaled using a computer. The decision to make the otherwise accurately rendered animals almost human-size gives an oddly anthropomorphizing effect. Conversely, in Cybernetically Engineered Cloned and Nanonised Rabbit this same scanned information has been used to produce a miniature silver version, hinting at the realm where science meets myth and legend.

Chemical Life Support includes several compelling figurative sculptures of people who keep chronic illness at bay with drugs. Each sculpture is cast from polymer wax mixed with the drug that keeps each subject alive. The reclining individual figures are positioned as if at zero gravity, conceived so that they barely touch the plinths on which they are set. Innoscience, 2004, is a figure of Quinn's own baby son, Lucas, who suffers from a milk allergy; thus the wax has been mixed with the chemically produced milk-free substitute that has been used to sustain him. For the figure of Silvia Petretti, who is HIV positive, the casting wax has been mixed with her required anti-viral drug. Transplant survivor Carl Whittaker's wax mould contains the drug cocktail that keeps his body from rejecting its own organs. To the viewer, these serene bodies seem healthy and whole; only the titles hint at the secret that is contained within their very substance of lives that are precarious and fragile.

Quinn's new sculptures develop key ideas that can be traced through his earlier work, such as the 'Eternal Spring' installations where he preserved flowers in their most perfect bloom by plunging them into sub-zero silicone tanks and kept them alive by virtue of 'umbilical' electrical cords. In 'The Complete Marbles', figures of people who had lost limbs or were born without them were carved in marble in the classical manner as a way of re-reading the aspirations of Greek and Roman statuary and their reliance on a perceived, imagined and idealised whole. In this current exhibition, Quinn presents two marble heads of a blind man and woman, which appear like any other 'blind' classical sculpture. In this case, Quinn has made the blank stone eyes of classical sculpture (which were, of course, once vividly painted) equivalent with the literal limitations of human perception.

The sculptures Cybernetically Engineered, Cloned and Grown Rabbits recall Quinn's earlier work with DNA, including the portrait of Sir John Sulston, now on show at the National Portrait Gallery. These perfect replicas of disembowelled rabbits are, literally, clones that have been rescaled using a computer. The decision to make the otherwise accurately rendered animals almost human-size gives an oddly anthropomorphizing effect. Conversely, in Cybernetically Engineered Cloned and Nanonised Rabbit this same scanned information has been used to produce a miniature silver version, hinting at the realm where science meets myth and legend.