David Wojnarowicz

History Keeps Me Awake at Night

13 Jul - 30 Sep 2018

Installation view of David Wojnarowicz: History Keeps Me Awake at Night (Whitney Museum of American Art, New York, July 13-September 30, 2018). From left to right: Queer Basher/Icarus Falling, 1986; Unfinished Film (A Fire in My Belly), 1986-87; Unfinished Film (Mexico, etc... Peter, etc...), 1987; Unfinished Film (with sequence in memory of Peter Hujar), c. 1987; Unfinished Film (Mexico Film Footage II), c. 1988; A Worker, 1986. Photograph by Ron Amstutz

Installation view of David Wojnarowicz: History Keeps Me Awake at Night (Whitney Museum of American Art, New York, July 13-September 30, 2018). From left to right: Unfinished Film (A Fire in My Belly), 1986-87; Unfinished Film (Mexico, etc... Peter, etc...), 1987; Unfinished Film (with sequence in memory of Peter Hujar), c. 1987; Unfinished Film (Mexico Film Footage II), c. 1988; Water, 1987. Photograph by Ron Amstutz

Installation view of David Wojnarowicz: History Keeps Me Awake at Night (Whitney Museum of American Art, New York, July 13-September 30, 2018). Clockwise, from top left: Andreas Sterzing, Something Possible Everywhere: Pier 34, NYC, 1983-84; David Wojnarowicz, Fuck You Faggot Fucker, 1984; Peter Hujar, Untitled (Pier), 1983; Peter Hujar, Canal Street Piers: Krazy Kat Comic on Wall [by David Wojnarowicz], 1983; David Wojnarowicz, Untitled, 1982; David Wojnarowicz, Untitled (Slam Click), 1983. Photograph by Ron Amstutz

Installation view of David Wojnarowicz: History Keeps Me Awake at Night (Whitney Museum of American Art, New York, July 13-September 30, 2018). From left to right, top to bottom: Untitled (Falling Man and Map of the U.S.A.), 1982; Untitled (Burning House), 1982; 3 Teens Kill 4—No Motive poster, 1982-83; Untitled (Falling Man and Other Stencils), 1982; Untitled (Dog Head), 1982; David Wojnarowicz and Kiki Smith, Untitled (Psychiatric Clinic), 1983; Savarin Coffee, 1983; Hujar Dreaming, 1982; Meat Franks, 1983; True Myth (Kraft Grape Jelly), 1983; Diptych II, 1982; Untitled, 1985; Untitled (Running Soldier in Camouflage and Gunsight), 1982; Prison Rape, 1984; Untitled (Camouflaged Plane with Red Dancer), 1982; Delta Towels, 1983; Jean Genet Masturbating in Metteray Prison (London Broil), 1983; Untitled (Sirloin Steaks), 1983; David Wojnarowicz and Kiki Smith, Untitled (Skull with Fetish Figure and Globe), 1984; Tuna, 1983; Peter Hujar, Untitled (David Wojnarowicz), 1984; Untitled (Skull with globe in mouth), 1984; Untitled, 1982; Incident #2—Government Approved, 1984; Martinson Coffee, 1983; Untitled (Frog and Snake), 1983; Untitled (Two Heads), 1984. Photograph by Ron Amstutz

Installation view of David Wojnarowicz: History Keeps Me Awake at Night (Whitney Museum of American Art, New York, July 13-September 30, 2018). From left to right: He Kept Following Me, 1990; I Feel A Vague Nausea, 1990; Americans Can’t Deal with Death, 1990; We Are Born into a Preinvented Existence, 1990. Photograph by Ron Amstutz

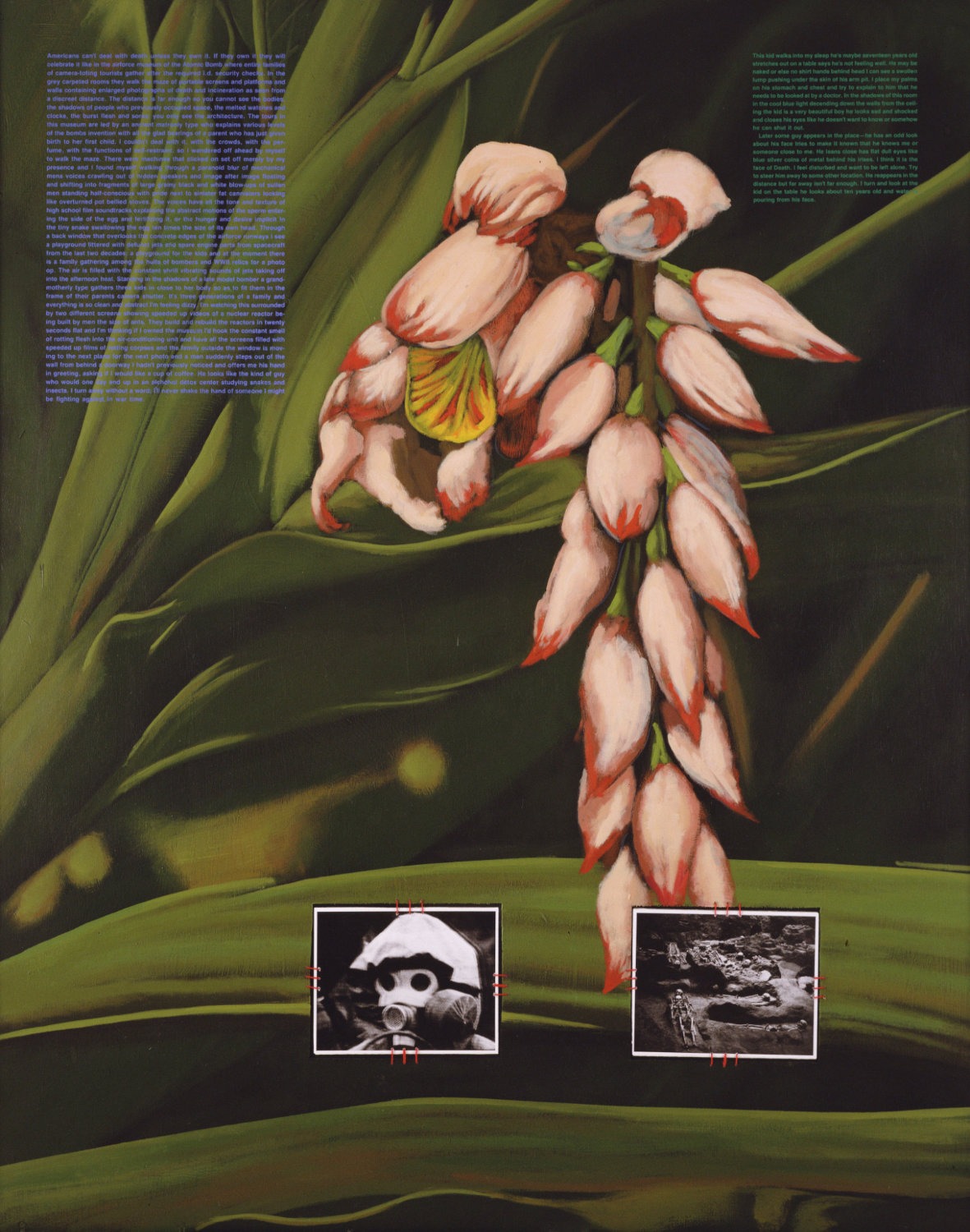

David Wojnarowicz (1954-1992). Americans Can’t Deal with Death, 1990. Two gelatin silver prints, acrylic, string, and screenprint on composition board 60 × 48 in. (152.4 × 121.9 cm). Collection of Eric Ceputis and David W. Williams. Image courtesy the Estate of David Wojnarowicz and P.P.O.W, New York

Installation view of David Wojnarowicz: History Keeps Me Awake at Night (Whitney Museum of American Art, New York, July 13-September 30, 2018). From left to right: Arthur Rimbaud in New York, 1978-79 (printed 1990); Arthur Rimbaud in New York, 1979; Arthur Rimbaud in New York, 1978-79 (printed 1990); Arthur Rimbaud in New York, 1978-79 (printed 1990); Autoportrait – New York, 1980; Arthur Rimbaud in New York, 1978-79 (printed 1990); Arthur Rimbaud in New York, 1978-79 (printed 1990); Rimbaud Mask, c. 1978; Untitled (Joseph Beuys), 1979; Untitled (Genet after Brassaï), 1979; Bill Burroughs’ Recurring Dream, 1978; Arthur Rimbaud in New York, 1978-79 (printed 2004). Photograph by Ron Amstutz

Installation view of David Wojnarowicz: History Keeps Me Awake at Night (Whitney Museum of American Art, New York, July 13-September 30, 2018). From left to right: Sex Series (for Marion Scemama), 1989; Untitled, 1987 (printed 1988); Untitled, 1987 (printed 1988); Untitled, 1987 (printed 1988); Untitled (Hujar Dead), 1988-89. Photograph by Ron Amstutz

Installation view of David Wojnarowicz: History Keeps Me Awake at Night (Whitney Museum of American Art, New York, July 13-September 30, 2018). From left to right: What Is This Little Guy’s Job in the World, 1990; Untitled (ACT-UP), 1990; Sub-Species Helms Senatorius, 1990; Bread Sculpture, 1988-89; Untitled (Face in Dirt), 1991 (printed 1993). Photograph by Ron Amstutz

David Wojnarowicz (1954-1992) with Tom Warren, Self-Portrait of David Wojnarowicz, 1983–84. Acrylic and collaged paper on gelatin silver print, 60 × 40 in. (152.4 × 101.6 cm). Collection of Brooke Garber Neidich and Daniel Neidich, Photograph by Ron Amstutz.

Beginning in the late 1970s, David Wojnarowicz (1954–1992) created a body of work that spanned photography, painting, music, film, sculpture, writing, and activism. Largely self-taught, he came to prominence in New York in the 1980s, a period marked by creative energy, financial precariousness, and profound cultural changes. Intersecting movements—graffiti, new and no wave music, conceptual photography, performance, and neo-expressionist painting—made New York a laboratory for innovation. Wojnarowicz refused a signature style, adopting a wide variety of techniques with an attitude of radical possibility. Distrustful of inherited structures—a feeling amplified by the resurgence of conservative politics—he varied his repertoire to better infiltrate the prevailing culture.

Wojnarowicz saw the outsider as his true subject. Queer and later diagnosed as HIV-positive, he became an impassioned advocate for people with AIDS when an inconceivable number of friends, lovers, and strangers were dying due to government inaction. Wojnarowicz’s work documents and illuminates a desperate period of American history: that of the AIDS crisis and culture wars of the late 1980s and early 1990s. But his rightful place is also among the raging and haunting iconoclastic voices, from Walt Whitman to William S. Burroughs, who explore American myths, their perpetuation, their repercussions, and their violence. Like theirs, his work deals directly with the timeless subjects of sex, spirituality, love, and loss. Wojnarowicz, who was thirty-seven when he died from AIDS-related complications, wrote: “To make the private into something public is an action that has terrific ramifications.”

This exhibition is co-curated by David Kiehl, Curator Emeritus, and David Breslin, DeMartini Family Curator and Director of the Collection.

Wojnarowicz saw the outsider as his true subject. Queer and later diagnosed as HIV-positive, he became an impassioned advocate for people with AIDS when an inconceivable number of friends, lovers, and strangers were dying due to government inaction. Wojnarowicz’s work documents and illuminates a desperate period of American history: that of the AIDS crisis and culture wars of the late 1980s and early 1990s. But his rightful place is also among the raging and haunting iconoclastic voices, from Walt Whitman to William S. Burroughs, who explore American myths, their perpetuation, their repercussions, and their violence. Like theirs, his work deals directly with the timeless subjects of sex, spirituality, love, and loss. Wojnarowicz, who was thirty-seven when he died from AIDS-related complications, wrote: “To make the private into something public is an action that has terrific ramifications.”

This exhibition is co-curated by David Kiehl, Curator Emeritus, and David Breslin, DeMartini Family Curator and Director of the Collection.