Ketty La Rocca

12 Apr - 29 Jun 2014

KETTY LA ROCCA

12 April - 29 June 2014

There is a quote by Marcia Tucker I’ve always loved (and often quoted), from her wonderfully titled essay The Attack of the Giant Ninja Mutant Barbies, in the catalogue for the exhibition Bad Girlsat New Museum, in 1994: “Language is more than just what is spoken and written; virtually all communication, social structures and systems rely in some way on language for their form. Whoever controls language - who speaks, who is listened to or heard – has everything to say about how people think and feel about themselves. Language is power. (...) Politics and language intersect in the form of attitudes, of talking down or looking up to, of patronising, respecting, ignoring, supporting, misinterpreting”. In a few lines, Tucker sums up a few decades of feminist critique, with her usual wit and clarity. And without even writing the word “woman”.

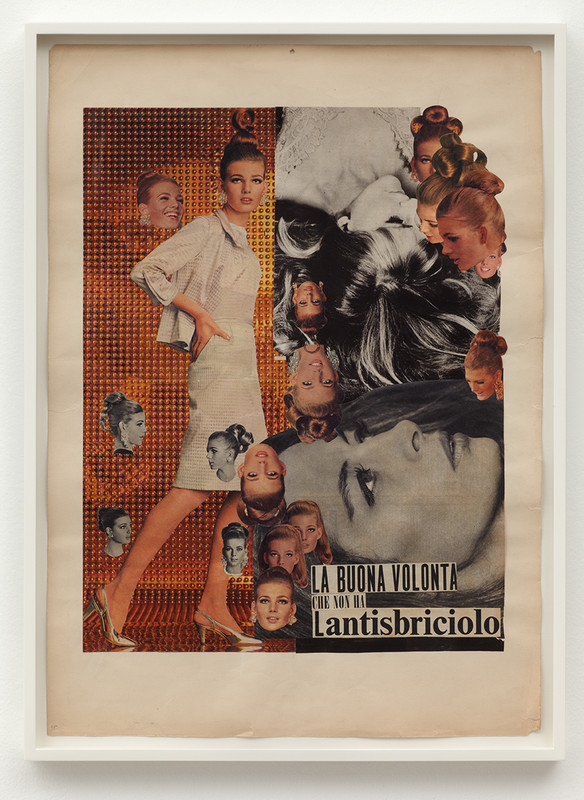

Music was one of Ketty La Rocca’s first experiences in the world of art (she attended the first Italian course in electronic music with Pietro Grossi at the Luigi Cherubini conservatorium in Florence, where La Rocca moved to from La Spezia, at 18), so that the issue of being “listened to or heard” was crucially framed in her work since the beginning. When she joined the Florentine group of concrete poets Gruppo 70 (active from ’63 to ‘68, despite its name), her aim was the subversion of the artificial “technological language” of the consumer society and the mass media. The group worked on forms of communication that were both visual and verbal, based on the language of news magazines and comics, but La Rocca was the only one (Gruppo 70 had no other female members, with the exception of Mirella Bentivoglio) to adopt a feminist way to guerrilla semiotics. She read Barthes, Eco, Levi-Strauss, Mac Luhan. Her first collages, like Sana come il pane quotidiano (Healthy like the daily bread, 1964-5), short-circuit the naked female body with advertising slogans and images of Asian children eating rice, as well as with the Lord’s Prayer’s “Give us this day our daily bread” – “and lead us not into temptation”, at a time in Italy when the ideological positions of the Catholic church and parties were not exactly womenfriendly. Sono felice (I’m happy, 1965), where a beautiful and perfectly made-up lady declares her happiness “after the dishes, after the washing, after the cleaning”, predates Martha Rosler’s Semiotics of the Kitchenby a decade.

La Rocca didn’t define herself a feminist, nor did she join any movement or group (like artist Carla Accardi did, for instance, as founder of the separatist collective Rivolta Femminilewith art critic Carla Lonzi, in 1970), but the attempt to undermine the authority of the written word, identified with a codified expression of patriarchal domination, was common ground. As Adrienne Rich wrote in The Burning of Paper Instead of Children(published in The Will to Change, 1971): “this is the oppressor's language / yet I need it to talk to you”. The body, or better, the gesture, became La Rocca’s key to individual expression. Photos of the artist’s hands, coupled with nonsense texts and verses, were the protagonists of her seminal book In principio erat (1971, In the beginning was – “the Word” being the obvious missing fragment of the biblical sentence), one of the first examples of Body Art.

Hands were a common metaphor of female industriousness (“Mani di fata”, Fairy hands, being a very popular knitting magazine), but they also evoked the idea of manipulation, from mani(hands, derived from Latin manus). Hands were again the subject of her video Appendice per una supplica (Appendix to an Appeal, 1972), presented at the 36th Venice Biennale, in the performance and videotape section, curated by Gerry Schum. In my head, these works are perennially linked to another non-verbal anthology: Bruno Munari’s ironical “Supplement to the Italian dictionary”, published in 1963, a book that examines “the different ways of talking without a single word being spoken, by using only the hands or the expressions of the face or the attitude of the body” so typical of Italian language, and so typically presented as a truism of Italian identity. When, with the series Riduzioni (Reductions), La Rocca decided to deconstruct the picture-perfect epic of Renaissance art history, she did it by using clichéd images of masterpieces, like Michelangelo’s David (David, 1501–1504), taken from the Florentine Alinari Archive, the world’s oldest photographic firm, founded in 1852. By retracing in ink the outline of each sculpture with her own, minute handwriting, the artist inscribed – “embroidered”, she said – each artwork with new meanings. She wrote in Italian, but the recursive words “I” and “you” are always in English, possibly as an additional reflection on “the oppressor’s language”. Art criticism, so full of dogmatic and self-referential inanity, was another target. La Rocca often displayed her Riduzioni together with a deliberately unintelligible text: “Starting from the moment when any development proceeds from a practical point of view, setting up as a precondition a concrete demand that would be acceptable in the frame of a perspective free from unobjective judgment, into a field so broad that it unavoidably encounters the assertion that it is not quite applicable to...”

La Rocca kept looking for new alphabets, free from the pronouncements of langue dominante (dominating language). “Nuovi Alfabeti” was also the title of an experimental TV program she worked for as a consultant, for Italy’s national public broadcasting company RAI. Aired for the first time on March 20th 1973 on the second channel, before the evening news, it marked a small revolution for deaf people: all the contents were both announced by an anchorwoman and translated into signs. It was a bold statement, since the (then) traditional language learning methods were based on lip reading, and thus focused on what was missing, i.e. the lack of hearing, instead of on the alternative ability to communicate fluently with hands. For the artist, who had also worked as an primary school teacher, it was another refusal of a language of exclusion. Significantly, after three years, the program was cancelled because of the protests of anti-sign language campaigners.

Barbara Casavecchia

12 April - 29 June 2014

There is a quote by Marcia Tucker I’ve always loved (and often quoted), from her wonderfully titled essay The Attack of the Giant Ninja Mutant Barbies, in the catalogue for the exhibition Bad Girlsat New Museum, in 1994: “Language is more than just what is spoken and written; virtually all communication, social structures and systems rely in some way on language for their form. Whoever controls language - who speaks, who is listened to or heard – has everything to say about how people think and feel about themselves. Language is power. (...) Politics and language intersect in the form of attitudes, of talking down or looking up to, of patronising, respecting, ignoring, supporting, misinterpreting”. In a few lines, Tucker sums up a few decades of feminist critique, with her usual wit and clarity. And without even writing the word “woman”.

Music was one of Ketty La Rocca’s first experiences in the world of art (she attended the first Italian course in electronic music with Pietro Grossi at the Luigi Cherubini conservatorium in Florence, where La Rocca moved to from La Spezia, at 18), so that the issue of being “listened to or heard” was crucially framed in her work since the beginning. When she joined the Florentine group of concrete poets Gruppo 70 (active from ’63 to ‘68, despite its name), her aim was the subversion of the artificial “technological language” of the consumer society and the mass media. The group worked on forms of communication that were both visual and verbal, based on the language of news magazines and comics, but La Rocca was the only one (Gruppo 70 had no other female members, with the exception of Mirella Bentivoglio) to adopt a feminist way to guerrilla semiotics. She read Barthes, Eco, Levi-Strauss, Mac Luhan. Her first collages, like Sana come il pane quotidiano (Healthy like the daily bread, 1964-5), short-circuit the naked female body with advertising slogans and images of Asian children eating rice, as well as with the Lord’s Prayer’s “Give us this day our daily bread” – “and lead us not into temptation”, at a time in Italy when the ideological positions of the Catholic church and parties were not exactly womenfriendly. Sono felice (I’m happy, 1965), where a beautiful and perfectly made-up lady declares her happiness “after the dishes, after the washing, after the cleaning”, predates Martha Rosler’s Semiotics of the Kitchenby a decade.

La Rocca didn’t define herself a feminist, nor did she join any movement or group (like artist Carla Accardi did, for instance, as founder of the separatist collective Rivolta Femminilewith art critic Carla Lonzi, in 1970), but the attempt to undermine the authority of the written word, identified with a codified expression of patriarchal domination, was common ground. As Adrienne Rich wrote in The Burning of Paper Instead of Children(published in The Will to Change, 1971): “this is the oppressor's language / yet I need it to talk to you”. The body, or better, the gesture, became La Rocca’s key to individual expression. Photos of the artist’s hands, coupled with nonsense texts and verses, were the protagonists of her seminal book In principio erat (1971, In the beginning was – “the Word” being the obvious missing fragment of the biblical sentence), one of the first examples of Body Art.

Hands were a common metaphor of female industriousness (“Mani di fata”, Fairy hands, being a very popular knitting magazine), but they also evoked the idea of manipulation, from mani(hands, derived from Latin manus). Hands were again the subject of her video Appendice per una supplica (Appendix to an Appeal, 1972), presented at the 36th Venice Biennale, in the performance and videotape section, curated by Gerry Schum. In my head, these works are perennially linked to another non-verbal anthology: Bruno Munari’s ironical “Supplement to the Italian dictionary”, published in 1963, a book that examines “the different ways of talking without a single word being spoken, by using only the hands or the expressions of the face or the attitude of the body” so typical of Italian language, and so typically presented as a truism of Italian identity. When, with the series Riduzioni (Reductions), La Rocca decided to deconstruct the picture-perfect epic of Renaissance art history, she did it by using clichéd images of masterpieces, like Michelangelo’s David (David, 1501–1504), taken from the Florentine Alinari Archive, the world’s oldest photographic firm, founded in 1852. By retracing in ink the outline of each sculpture with her own, minute handwriting, the artist inscribed – “embroidered”, she said – each artwork with new meanings. She wrote in Italian, but the recursive words “I” and “you” are always in English, possibly as an additional reflection on “the oppressor’s language”. Art criticism, so full of dogmatic and self-referential inanity, was another target. La Rocca often displayed her Riduzioni together with a deliberately unintelligible text: “Starting from the moment when any development proceeds from a practical point of view, setting up as a precondition a concrete demand that would be acceptable in the frame of a perspective free from unobjective judgment, into a field so broad that it unavoidably encounters the assertion that it is not quite applicable to...”

La Rocca kept looking for new alphabets, free from the pronouncements of langue dominante (dominating language). “Nuovi Alfabeti” was also the title of an experimental TV program she worked for as a consultant, for Italy’s national public broadcasting company RAI. Aired for the first time on March 20th 1973 on the second channel, before the evening news, it marked a small revolution for deaf people: all the contents were both announced by an anchorwoman and translated into signs. It was a bold statement, since the (then) traditional language learning methods were based on lip reading, and thus focused on what was missing, i.e. the lack of hearing, instead of on the alternative ability to communicate fluently with hands. For the artist, who had also worked as an primary school teacher, it was another refusal of a language of exclusion. Significantly, after three years, the program was cancelled because of the protests of anti-sign language campaigners.

Barbara Casavecchia