Tobias Teschner

17 Jan - 22 Feb 2015

TOBIAS TESCHNER

Yellow Snow

17 January - 22 February 2015

Ilderton Road Striding down Ilderton Road towards Tobias Teschner’s studio is a bleak experience.On the face of it, not much here has changed in years. It’s a cold December afternoon, Millwall Football Club stands ahead, and the light industry surrounding the sun-bleached stadium is lit by neoteric single-deck buses that hum urgently at temporary lights. Arriving at an ex-Jewson depot emblazoned with the words ‘Waste Disposal’, I call Teschner. ‘I’ll be right out’ he says, and immediately emerges from a small door 100 yards away. He’s well dressed, wears shoes and has neat hair. A typical warren of small units opens out and, in his rented space, I’m offered Turkish coffee. Surrounding us are books on Marx, religion and the Third Reich.

We sit down and talk. Subjects include ‘presentist’ ideas of the ‘contemporary’, theorists of Conceptual Art who effectively act as disenchanted labourer-priests of the negative, Jena Romanticism, affirmative modes of connectivity within digital subject matter (including post-Internet painting-asinstallation in London and Zurich, a rational structure, which we agree acts as a system for success in the international art world), the nonegalitarian nature of Instagram as a curatorial platform, the consequences and possibilities produced by ongoing austerity measures in the UK, regeneration and displacement, regressive tradition and radical museology. We discuss Sigmar Polke’s exhibition at Tate, Anselm Kiefer’s at the Royal Academy and Jonathan Meese’s show at Modern Art. We hash out artists’ use of the swastika as decoration.

Then we move on to Teschner’s German heritage, his dark confidence in filth, and the buried eroticism held within the semi-visible figures he paints. Teschner is religious. He goes to church every Wednesday and Sunday, his grandmother’s aunt was a medium, and his belief offers him a spiritual code with which to construct a schizophrenic ambivalence towards existence. Within this framework, we discuss the demolition of nearby Elephant and Castle’s Heygate Estate, its community’s annihilation, mass rape as a weapon in the Congo, Joseph Conrad’s Heart of Darkness, the Thames Estuary’s position in relation to his homeland, the Brothers Grimm’s fairy tales, the theme of maternal cannibalism in Hansel and Gretel, and the splitting of good and evil in a forest hut made of candy. Similar to this fable, the figures in his paintings contain a bittersweet taste and radiate a harsh positivity

Novalis This ethical ambiguity is evident in Teschner’s painting Novalis, where a window presents a night scene in which a painted glitter-glaze of stars sits behind a Weimar Republic lace curtain. The German poet and philosopher connected to the Jena school whose name has been used for the title of this work spent his childhood on his family’s estate and used it as the starting point for his travels into the Harz Mountains. Similarly, Teschner’s hometown of Blankenburg offered easy access forthe artist to visit the same mountain range. If Teschner’s painting contains a number of fragments that provide homage to Novalis, they also combine a rationalrepresentation of a naïve folk pattern that shows a mother bird eating its offspring, an obvious link to Grimm’s cannibalism. In turn, the baby bird and its Wittgensteinian bird/rabbit doubling, connects to Teschner’s collection of pigeon droppings, which sits above his bookshelf . This scatological archive stems from an experience in his previous studio nearby, where walled-up povertystricken adult birds survived by eating their young, and is worked into painterly blobs in his pictures. Again, annihilation, survival and candy coloured dirt combine. He goes on to describe a politically incorrect German maxim that goes something like ‘if a beautiful woman is too perfect, she becomes unappealing and repellent’. Essentially, a bit of dirt and a bad attitude can go a long way.

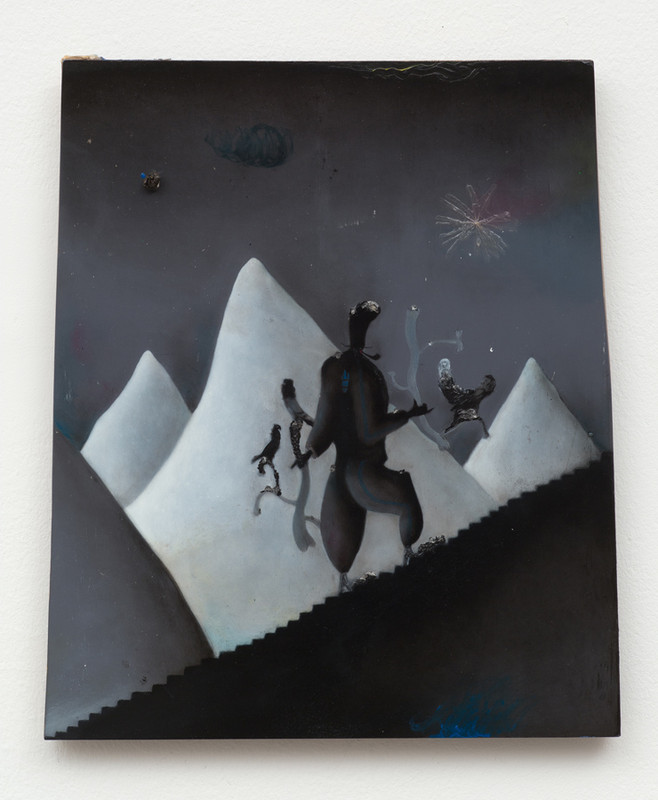

Rye Lane At this point Teschner starts to scare me a little, which takes some doing. He’s performing the bad guy too well, talking about war crimes and asking if we’d be truly happy if we had world peace. Acts of self-sacrifice in conflict sometimes produce unassailable moments of evil and, as a fucked-up fantasy, totalapebabe shows us how intentional malevolence can arrive in small stages over time via indistinct ideological gradations, a fact that links to the ongoing gentrification of south-east London. A monstrous and clichéd trope in painting – the heightened consciousness of an anxious Guston-esque eye smoking a cigarette – and a face’s profile that doubles as theatrical curtains, is used to open a picture that presents a central phallus, a little ape, another forest scene and a skull, all of which compete for the viewer’s attention. Nothing is clear in this threshold zone bar a key motif, a bright white Nike logo, a sign of the benign and savage culture of Peckham’s new wealthy inhabitants. Mediator 2 presents an anti-hero archetype to this populace in the form of a dark-pope hipster, a lofty man that sports a beard and a tall hat. This king, young warrior, druid or magician is a supernatural alcoholic, a homeless Rambo, a dark and critical painter, and a ghostly smoking apparition. This thingman exists in the shadows of Rye Lane, abhors the mainstream, and despises faux countercultural doctrines.

Goofy Teschner puts on his act again. We’re stood in front of a painting with the working title Yellow Snow and his evil shtick around diamonds in the dirt, the unattractive nature of perfection and a surrendering to flawed, reprehensible beauty heads in a new direction. It turns out that fresh snow’s innocent appearance, its muffled sound and its clear atmosphere is one of his favourite seasonal experiences. However, Teschner also prefers this bright white substance warmed-up, trodden down and dirty. As if through example, a madman in his picture pisses a small stain into a pure winter landscape of baby blue and pink by a tree; he’s peacefully alone in nature while the moon beams down from above. Painted on an irregular shaped support, this work takes the form of another dark phallus that doubles as the rudimentary features of a genial face, and triples as another forest at night. With my attention distracted by a Chris Ofili elephant shit style support in the form of a small Greek ornament, it takes a while to notice a disturbing animal cartoon character gazing down from the dark tip of the painting. Goofy looks affable: he’s got a cigarette on the go as he watches the scene around him. According to Teschner, the collection of images in this painting is negative ‘stuff’ that its main figure has accepted as an inevitable part of his life. He/it exists in an ideal world of empathy with dark and light, a place in which we mightregenerate, or allow new things to occur

In many respects, Teschner’s art is opposed to pure nonsense because nonsense is an object of recognition. Instead, the ridiculous signs he use ‘show’ rather than ‘designate’, operate in an asymmetric or isomorphic crease between the utterable and the visible. As I bid farewell to him and walk to South Bermondsey station, the night draws in and I start to feel at home in the bi-polar city that surrounds me.

Text by Andrew Hunt

Yellow Snow

17 January - 22 February 2015

Ilderton Road Striding down Ilderton Road towards Tobias Teschner’s studio is a bleak experience.On the face of it, not much here has changed in years. It’s a cold December afternoon, Millwall Football Club stands ahead, and the light industry surrounding the sun-bleached stadium is lit by neoteric single-deck buses that hum urgently at temporary lights. Arriving at an ex-Jewson depot emblazoned with the words ‘Waste Disposal’, I call Teschner. ‘I’ll be right out’ he says, and immediately emerges from a small door 100 yards away. He’s well dressed, wears shoes and has neat hair. A typical warren of small units opens out and, in his rented space, I’m offered Turkish coffee. Surrounding us are books on Marx, religion and the Third Reich.

We sit down and talk. Subjects include ‘presentist’ ideas of the ‘contemporary’, theorists of Conceptual Art who effectively act as disenchanted labourer-priests of the negative, Jena Romanticism, affirmative modes of connectivity within digital subject matter (including post-Internet painting-asinstallation in London and Zurich, a rational structure, which we agree acts as a system for success in the international art world), the nonegalitarian nature of Instagram as a curatorial platform, the consequences and possibilities produced by ongoing austerity measures in the UK, regeneration and displacement, regressive tradition and radical museology. We discuss Sigmar Polke’s exhibition at Tate, Anselm Kiefer’s at the Royal Academy and Jonathan Meese’s show at Modern Art. We hash out artists’ use of the swastika as decoration.

Then we move on to Teschner’s German heritage, his dark confidence in filth, and the buried eroticism held within the semi-visible figures he paints. Teschner is religious. He goes to church every Wednesday and Sunday, his grandmother’s aunt was a medium, and his belief offers him a spiritual code with which to construct a schizophrenic ambivalence towards existence. Within this framework, we discuss the demolition of nearby Elephant and Castle’s Heygate Estate, its community’s annihilation, mass rape as a weapon in the Congo, Joseph Conrad’s Heart of Darkness, the Thames Estuary’s position in relation to his homeland, the Brothers Grimm’s fairy tales, the theme of maternal cannibalism in Hansel and Gretel, and the splitting of good and evil in a forest hut made of candy. Similar to this fable, the figures in his paintings contain a bittersweet taste and radiate a harsh positivity

Novalis This ethical ambiguity is evident in Teschner’s painting Novalis, where a window presents a night scene in which a painted glitter-glaze of stars sits behind a Weimar Republic lace curtain. The German poet and philosopher connected to the Jena school whose name has been used for the title of this work spent his childhood on his family’s estate and used it as the starting point for his travels into the Harz Mountains. Similarly, Teschner’s hometown of Blankenburg offered easy access forthe artist to visit the same mountain range. If Teschner’s painting contains a number of fragments that provide homage to Novalis, they also combine a rationalrepresentation of a naïve folk pattern that shows a mother bird eating its offspring, an obvious link to Grimm’s cannibalism. In turn, the baby bird and its Wittgensteinian bird/rabbit doubling, connects to Teschner’s collection of pigeon droppings, which sits above his bookshelf . This scatological archive stems from an experience in his previous studio nearby, where walled-up povertystricken adult birds survived by eating their young, and is worked into painterly blobs in his pictures. Again, annihilation, survival and candy coloured dirt combine. He goes on to describe a politically incorrect German maxim that goes something like ‘if a beautiful woman is too perfect, she becomes unappealing and repellent’. Essentially, a bit of dirt and a bad attitude can go a long way.

Rye Lane At this point Teschner starts to scare me a little, which takes some doing. He’s performing the bad guy too well, talking about war crimes and asking if we’d be truly happy if we had world peace. Acts of self-sacrifice in conflict sometimes produce unassailable moments of evil and, as a fucked-up fantasy, totalapebabe shows us how intentional malevolence can arrive in small stages over time via indistinct ideological gradations, a fact that links to the ongoing gentrification of south-east London. A monstrous and clichéd trope in painting – the heightened consciousness of an anxious Guston-esque eye smoking a cigarette – and a face’s profile that doubles as theatrical curtains, is used to open a picture that presents a central phallus, a little ape, another forest scene and a skull, all of which compete for the viewer’s attention. Nothing is clear in this threshold zone bar a key motif, a bright white Nike logo, a sign of the benign and savage culture of Peckham’s new wealthy inhabitants. Mediator 2 presents an anti-hero archetype to this populace in the form of a dark-pope hipster, a lofty man that sports a beard and a tall hat. This king, young warrior, druid or magician is a supernatural alcoholic, a homeless Rambo, a dark and critical painter, and a ghostly smoking apparition. This thingman exists in the shadows of Rye Lane, abhors the mainstream, and despises faux countercultural doctrines.

Goofy Teschner puts on his act again. We’re stood in front of a painting with the working title Yellow Snow and his evil shtick around diamonds in the dirt, the unattractive nature of perfection and a surrendering to flawed, reprehensible beauty heads in a new direction. It turns out that fresh snow’s innocent appearance, its muffled sound and its clear atmosphere is one of his favourite seasonal experiences. However, Teschner also prefers this bright white substance warmed-up, trodden down and dirty. As if through example, a madman in his picture pisses a small stain into a pure winter landscape of baby blue and pink by a tree; he’s peacefully alone in nature while the moon beams down from above. Painted on an irregular shaped support, this work takes the form of another dark phallus that doubles as the rudimentary features of a genial face, and triples as another forest at night. With my attention distracted by a Chris Ofili elephant shit style support in the form of a small Greek ornament, it takes a while to notice a disturbing animal cartoon character gazing down from the dark tip of the painting. Goofy looks affable: he’s got a cigarette on the go as he watches the scene around him. According to Teschner, the collection of images in this painting is negative ‘stuff’ that its main figure has accepted as an inevitable part of his life. He/it exists in an ideal world of empathy with dark and light, a place in which we mightregenerate, or allow new things to occur

In many respects, Teschner’s art is opposed to pure nonsense because nonsense is an object of recognition. Instead, the ridiculous signs he use ‘show’ rather than ‘designate’, operate in an asymmetric or isomorphic crease between the utterable and the visible. As I bid farewell to him and walk to South Bermondsey station, the night draws in and I start to feel at home in the bi-polar city that surrounds me.

Text by Andrew Hunt