Cristof Yvoré

02 Mar - 12 Apr 2014

CRISTOF YVORÉ

Hommage

2 March - 12 April 2014

With the exhibition ‘Hommage’ Zeno X Gallery wishes to honour an extraordinary artist, who left this world too young. Cristof Yvoré (1967-2013) passed away on Monday, December 2, 2013. At the time, he was working on a new solo exhibition for the gallery, but this was unfortunately never completed. ‘Hommage’ brings together recent works and paintings from different periods, allowing the visitor to contemplate different aspects of Yvoré’s work.

A film by David Dupont which shows the artists at work in his studio in Marseille, can be viewed in the exhibition space. We are very grateful for the beautiful work Cristof Yvoré has left us, after a long collaboration of almost 20 years, since 1994. For us, the story is not over yet.

In May 2013, FRAC Provence-Alpes-Côte-d’Azur in Marseille organised a solo exhibition of Cristof Yvore in Lurs (FR). A few months later, a second solo exhibition was on view at Museum of Contemporary Art, Villa Croce in Genoa (IT). In connection with these two exhibitions, an extensive catalogue was published. FRAC PACA acquired three paintings by Cristof Yvore last year. From the 14th until the 30th of March, 2014 the museum will present these works in commemoration of the artist.

Cristof Yvoré’s Archetypical Paintings When I saw Cristof Yvoré’s paintings for the first time, reproduced on a small catalogue, my immediate response was one of dismissal. What on earth did it mean to create small apparently out-dated still-lives, which could have emerged from a thrift shop? Why obsessively focus on insignificant and neutral subjects? Yet there was something in these images, which made them unique. I don’t know if it was their thick painterly presence or the vaguely metaphysical atmosphere they evoked, but they would not leave my imagination, and remained alive in my memory, as a sort of open question on what painting could or could not be.

I decided I needed to see the works in real life in order to free myself from their haunting presence. Thus I planned a visit to Cristof Yvoré’s studio. It turned out to be an experience of enlightenment: I found myself totally absorbed and seduced in a succession of still lives and abstract spaces, in which what captivated my attention was the paint itself, how it defined forms through nuances of colours, how it created a closed universe in which emptiness was articulated through the volume of different objects, how the superimposition of multiple brushstrokes of pigment was not expressionist or instinctive but calibrated and precise, capable of defining objects and spaces.

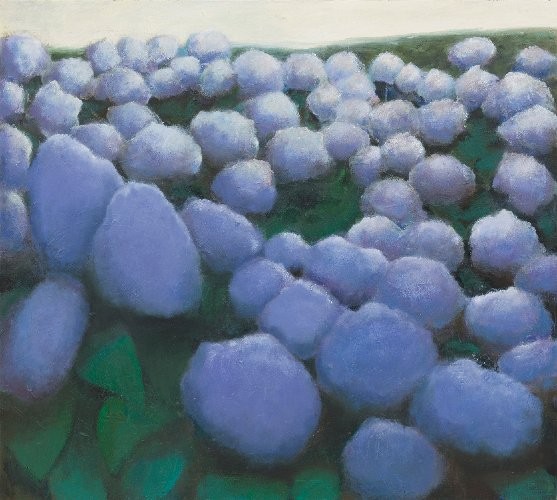

There is nothing modern, digital or photographic about these small and medium sized canvases on which multiple layers of paint have been layered to a point of total saturation. Instead they feel suspended out of time as if their very existence could question the notion of a progressive development in art history. Cristof Yvoré’s paintings portray vases of flowers, corners of rooms, balloons on a ceiling, empty plates, pots or jars, close-ups of fruits or vegetables that simply exist occupying the canvas and denying any trace of human presence or narrative; architectural non-places and still-lives, consumed by visual culture to such an extent that they evoke a constant sense of dejà-vu. The sophisticated balance between compositional elements and the dissonance in the choice of colours and texture, as much as the anonymous nature of the images allows for them to become, for each viewer, acquired memories, non-subjects that already occupy our unconscious. This is not related to any form of esoteric or mysterious vision but to the fact that Yvoré paints from memory images of unspecific, often anonymous, places or still lives, stripped of any specific details or narrative elements.

Yvoré talks unwillingly about what is the origin of his work, which has coherently developed since the beginning of his career in the field of figuration. ‘The process of executing each painting is quite long; I rethink the figure and the background several times and load them with successive thick layers of paint. By applying paint so extravagantly I run the risk that at any moment each painting could deteriorate into a thick crust. I play with the possibility of going as far as the boundary beyond which everything flips over into a complete mess. Having reached that line I can decide whether to start all over again or just to carry on.’

There is in his work a deep knowledge of painting’s history, and numerous formal references. Yet even if Cristof Yvoré’s work can be analysed through the lens of art history, it is important to contextualize his canvases in the art that is being produced today.

The history of painting in the south of France and in particular Cézanne’s heritage of ‘constructive brushstrokes’ of pure colour can be mentioned as reference for Yvoré’s work; yet I feel it is important to relate his artistic production with the developments of Italian early 20th century painting (Pittura Metafisica, Novecento Italiano) to understand the complex nature of his work. If Giorgio Morandi’s seductive and beautiful paintings were born on nuances of semi-colours, through a unique unity between space and objects, Yvoré’s works are marked by the essential archaic sculptural presence of his objects, which recalling some of Carlo Carra’s early metaphysical experiments, develop through the contrast of volumes.

Even if Yvoré’s paintings could be read as obsessive, introvert experiments, isolated from contemporary artistic developments, after careful analysis his oeuvre manifests itself as a form of post-conceptual practice. This is clear when comparing his still-lives with Morandi’s production. If the Italian master worked in a claustrophobic universe in which the still-lives he created and obsessively portrayed, became an existential limit for the definition of his poetics, Yvorè is apparently indifferent to the subjects he decides to portray. I say apparently because even if it is undeniable that there is no research for the subject or theme of his paintings there is a conscious decision to depict anonymous subjects. Instead of choosing images in some way loaded with personal meanings or emotions, Yvoré singles out insignificant memories or better abstract memories of non-places that allow the practice of painting of become more important than the painting itself.

Since the beginning of his career, this artist has chosen to work as a figurative painter, yet none of his subjects can possibly have any relevance to his personal life or to our vision of reality. His paintings are always articulated around an idea of absence and emptiness: the corner of a room, the curtains bathed in sunlight, the details of a vase of flowers, a pair of empty plates, yet the canvas is so thick with the multiple layers of paint, which he mixes personally, that the emptiness is contradicted by the feeling of painterly over-saturation. Similarly his canvases evoke a sense of claustrophobia due to the fact that there is no horizon that opens up to a viewer, his subjects are shoved a little to close to us; the corners of his anonymous rooms are dead ends that do not allow for our gaze to move or explore the spaces he depicts. These paintings aren’t windows that open up but instead spaces over-saturated with matter. Therefore the superimposition of multiple layers of paint metaphorically represents the number of times these subjects have been represented in the history of western art. Can an empty jar or vase of flowers still be the subject of a painting? The mechanism of this work is fascinating as what irresistibly pulls you inside the work is the fact that the work itself refuses any interpretation.

There is a profound dichotomy in the work, which is post-conceptual in the sense that it is born out of multiple contradictions that articulate the question of what figurative painting can be today, but, on the other hand, the elaborate painterly nature of the work, as well as the actual execution of each painting, involves the artist in months of intense personal effort. Working with a subtle toned palette of greys, pinks, beiges and browns in which hues of red or blue occasionally stand out, Yvoré seems to be experimenting on the limit of what a painting is and can be. It is as if the modernist lecture of reducing a painting to canvas and paint is taken one step further. Cristof Yvoré seems to answer the question of what a painting can be in post-conceptual mode: a painting is a painting is a painting, or better a painting is a painting of paint that paints something. (Ilaria Bonacossa)

Hommage

2 March - 12 April 2014

With the exhibition ‘Hommage’ Zeno X Gallery wishes to honour an extraordinary artist, who left this world too young. Cristof Yvoré (1967-2013) passed away on Monday, December 2, 2013. At the time, he was working on a new solo exhibition for the gallery, but this was unfortunately never completed. ‘Hommage’ brings together recent works and paintings from different periods, allowing the visitor to contemplate different aspects of Yvoré’s work.

A film by David Dupont which shows the artists at work in his studio in Marseille, can be viewed in the exhibition space. We are very grateful for the beautiful work Cristof Yvoré has left us, after a long collaboration of almost 20 years, since 1994. For us, the story is not over yet.

In May 2013, FRAC Provence-Alpes-Côte-d’Azur in Marseille organised a solo exhibition of Cristof Yvore in Lurs (FR). A few months later, a second solo exhibition was on view at Museum of Contemporary Art, Villa Croce in Genoa (IT). In connection with these two exhibitions, an extensive catalogue was published. FRAC PACA acquired three paintings by Cristof Yvore last year. From the 14th until the 30th of March, 2014 the museum will present these works in commemoration of the artist.

Cristof Yvoré’s Archetypical Paintings When I saw Cristof Yvoré’s paintings for the first time, reproduced on a small catalogue, my immediate response was one of dismissal. What on earth did it mean to create small apparently out-dated still-lives, which could have emerged from a thrift shop? Why obsessively focus on insignificant and neutral subjects? Yet there was something in these images, which made them unique. I don’t know if it was their thick painterly presence or the vaguely metaphysical atmosphere they evoked, but they would not leave my imagination, and remained alive in my memory, as a sort of open question on what painting could or could not be.

I decided I needed to see the works in real life in order to free myself from their haunting presence. Thus I planned a visit to Cristof Yvoré’s studio. It turned out to be an experience of enlightenment: I found myself totally absorbed and seduced in a succession of still lives and abstract spaces, in which what captivated my attention was the paint itself, how it defined forms through nuances of colours, how it created a closed universe in which emptiness was articulated through the volume of different objects, how the superimposition of multiple brushstrokes of pigment was not expressionist or instinctive but calibrated and precise, capable of defining objects and spaces.

There is nothing modern, digital or photographic about these small and medium sized canvases on which multiple layers of paint have been layered to a point of total saturation. Instead they feel suspended out of time as if their very existence could question the notion of a progressive development in art history. Cristof Yvoré’s paintings portray vases of flowers, corners of rooms, balloons on a ceiling, empty plates, pots or jars, close-ups of fruits or vegetables that simply exist occupying the canvas and denying any trace of human presence or narrative; architectural non-places and still-lives, consumed by visual culture to such an extent that they evoke a constant sense of dejà-vu. The sophisticated balance between compositional elements and the dissonance in the choice of colours and texture, as much as the anonymous nature of the images allows for them to become, for each viewer, acquired memories, non-subjects that already occupy our unconscious. This is not related to any form of esoteric or mysterious vision but to the fact that Yvoré paints from memory images of unspecific, often anonymous, places or still lives, stripped of any specific details or narrative elements.

Yvoré talks unwillingly about what is the origin of his work, which has coherently developed since the beginning of his career in the field of figuration. ‘The process of executing each painting is quite long; I rethink the figure and the background several times and load them with successive thick layers of paint. By applying paint so extravagantly I run the risk that at any moment each painting could deteriorate into a thick crust. I play with the possibility of going as far as the boundary beyond which everything flips over into a complete mess. Having reached that line I can decide whether to start all over again or just to carry on.’

There is in his work a deep knowledge of painting’s history, and numerous formal references. Yet even if Cristof Yvoré’s work can be analysed through the lens of art history, it is important to contextualize his canvases in the art that is being produced today.

The history of painting in the south of France and in particular Cézanne’s heritage of ‘constructive brushstrokes’ of pure colour can be mentioned as reference for Yvoré’s work; yet I feel it is important to relate his artistic production with the developments of Italian early 20th century painting (Pittura Metafisica, Novecento Italiano) to understand the complex nature of his work. If Giorgio Morandi’s seductive and beautiful paintings were born on nuances of semi-colours, through a unique unity between space and objects, Yvoré’s works are marked by the essential archaic sculptural presence of his objects, which recalling some of Carlo Carra’s early metaphysical experiments, develop through the contrast of volumes.

Even if Yvoré’s paintings could be read as obsessive, introvert experiments, isolated from contemporary artistic developments, after careful analysis his oeuvre manifests itself as a form of post-conceptual practice. This is clear when comparing his still-lives with Morandi’s production. If the Italian master worked in a claustrophobic universe in which the still-lives he created and obsessively portrayed, became an existential limit for the definition of his poetics, Yvorè is apparently indifferent to the subjects he decides to portray. I say apparently because even if it is undeniable that there is no research for the subject or theme of his paintings there is a conscious decision to depict anonymous subjects. Instead of choosing images in some way loaded with personal meanings or emotions, Yvoré singles out insignificant memories or better abstract memories of non-places that allow the practice of painting of become more important than the painting itself.

Since the beginning of his career, this artist has chosen to work as a figurative painter, yet none of his subjects can possibly have any relevance to his personal life or to our vision of reality. His paintings are always articulated around an idea of absence and emptiness: the corner of a room, the curtains bathed in sunlight, the details of a vase of flowers, a pair of empty plates, yet the canvas is so thick with the multiple layers of paint, which he mixes personally, that the emptiness is contradicted by the feeling of painterly over-saturation. Similarly his canvases evoke a sense of claustrophobia due to the fact that there is no horizon that opens up to a viewer, his subjects are shoved a little to close to us; the corners of his anonymous rooms are dead ends that do not allow for our gaze to move or explore the spaces he depicts. These paintings aren’t windows that open up but instead spaces over-saturated with matter. Therefore the superimposition of multiple layers of paint metaphorically represents the number of times these subjects have been represented in the history of western art. Can an empty jar or vase of flowers still be the subject of a painting? The mechanism of this work is fascinating as what irresistibly pulls you inside the work is the fact that the work itself refuses any interpretation.

There is a profound dichotomy in the work, which is post-conceptual in the sense that it is born out of multiple contradictions that articulate the question of what figurative painting can be today, but, on the other hand, the elaborate painterly nature of the work, as well as the actual execution of each painting, involves the artist in months of intense personal effort. Working with a subtle toned palette of greys, pinks, beiges and browns in which hues of red or blue occasionally stand out, Yvoré seems to be experimenting on the limit of what a painting is and can be. It is as if the modernist lecture of reducing a painting to canvas and paint is taken one step further. Cristof Yvoré seems to answer the question of what a painting can be in post-conceptual mode: a painting is a painting is a painting, or better a painting is a painting of paint that paints something. (Ilaria Bonacossa)