Semyon Faibisovich

12 Jan - 02 Feb 2013

© Semyon Faibisovich

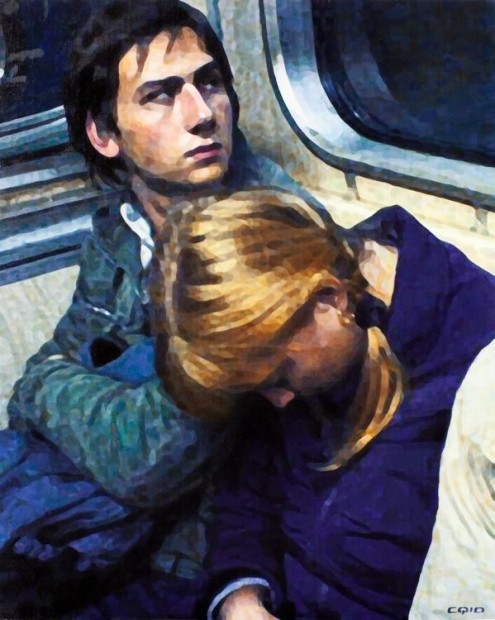

A Lad with Glowing Eyes from the cycle MOSCOW SUBWAY REVISITED, 2010

Mixed media, oil on canvas

180 x 145 cm

A Lad with Glowing Eyes from the cycle MOSCOW SUBWAY REVISITED, 2010

Mixed media, oil on canvas

180 x 145 cm

SEMYON FAIBISOVICH

Moscow & Muscovites

12 January – 2 February 2013

Semyon Faibisovich’s breakthrough came in 1980s with a series of paintings that collectively constituted a portrait of the Soviet era. Unlike the artists associated with Sots Art and Moscow conceptual art, who sought to portray the system using the very same symbols and signs that it itself employed (banners, slogans, leaders’ portraits, typical bits of text), Faibisovich was interested in the visual aspects of the system, the aspects that had not been properly reflected on and articulated. The things that are looked at by everybody yet seen by very few: the commonplace, even banal episodes of everyday life, faces gloomy as if bearing an invisible and identical stamp, the thick air of oppression — all of which, in his opinion, was as revealing about the life in USSR as its official symbols. And also light, the sunlight that helps to overcome the grey and listless stuff of reality.

The artist continued to stare attentively at the reality around him and producing works in the style which could be called ‘hypnorealism’ until the beginning of the 1990s, when the Soviet reality went away. And so the artist switched from the object that he sees to the process of seeing itself. His ‘Evidence’ project explores the optics of seeing with its effects and defects which together alter the way we see the world (even if we usually don’t notice these alterations): blind spots in the eye, the morning- or alcohol-induced double vision, the ‘residual vision’ — when we close our eyes and the capillary-laced eyelids act as screens, showing what we’ve just seen, only in the negative. The artist is observing and showing us how these negatives form, blurring the line between the real and the abstract.

In 1995 Faibisovich quits painting and devotes several years to writing. Towards the end of the decade he comes back to being an artist proper, this time engaging in photography, installations and video art. The full-fledged comeback to painting had to wait until 2007, when he felt that the new era had firmly established itself and it was time to paint its portrait — using tools that were up to date and up to the task. The new technology is essentially tripartite, involving low-resolution mobile camera shots, a digital painting game of augmenting the shots with computer photo editors and printing the result on canvas — and, finally, the traditional oil painting. Mixing the three technologies, merging the three processes into one, the artist produces a kind of a new breed of visual art — a new language to use when confronting the reality around him.

Moscow & Muscovites

12 January – 2 February 2013

Semyon Faibisovich’s breakthrough came in 1980s with a series of paintings that collectively constituted a portrait of the Soviet era. Unlike the artists associated with Sots Art and Moscow conceptual art, who sought to portray the system using the very same symbols and signs that it itself employed (banners, slogans, leaders’ portraits, typical bits of text), Faibisovich was interested in the visual aspects of the system, the aspects that had not been properly reflected on and articulated. The things that are looked at by everybody yet seen by very few: the commonplace, even banal episodes of everyday life, faces gloomy as if bearing an invisible and identical stamp, the thick air of oppression — all of which, in his opinion, was as revealing about the life in USSR as its official symbols. And also light, the sunlight that helps to overcome the grey and listless stuff of reality.

The artist continued to stare attentively at the reality around him and producing works in the style which could be called ‘hypnorealism’ until the beginning of the 1990s, when the Soviet reality went away. And so the artist switched from the object that he sees to the process of seeing itself. His ‘Evidence’ project explores the optics of seeing with its effects and defects which together alter the way we see the world (even if we usually don’t notice these alterations): blind spots in the eye, the morning- or alcohol-induced double vision, the ‘residual vision’ — when we close our eyes and the capillary-laced eyelids act as screens, showing what we’ve just seen, only in the negative. The artist is observing and showing us how these negatives form, blurring the line between the real and the abstract.

In 1995 Faibisovich quits painting and devotes several years to writing. Towards the end of the decade he comes back to being an artist proper, this time engaging in photography, installations and video art. The full-fledged comeback to painting had to wait until 2007, when he felt that the new era had firmly established itself and it was time to paint its portrait — using tools that were up to date and up to the task. The new technology is essentially tripartite, involving low-resolution mobile camera shots, a digital painting game of augmenting the shots with computer photo editors and printing the result on canvas — and, finally, the traditional oil painting. Mixing the three technologies, merging the three processes into one, the artist produces a kind of a new breed of visual art — a new language to use when confronting the reality around him.