Art of Prehistoric Times

05 Jan 2016

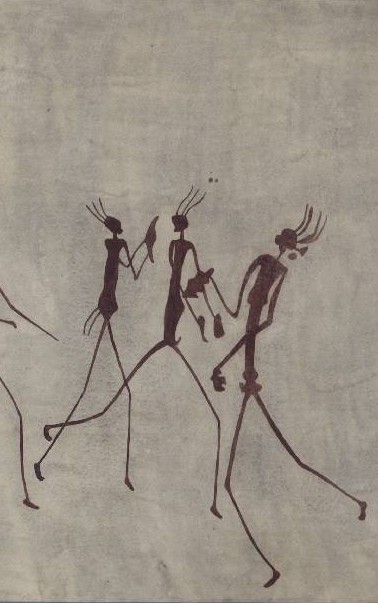

Procession (Detail). Zimbabwe, Chinamora, Massimbura. 8.000-2.000 v. Chr.

© Frobenius-Institute Frankfurt am Main

© Frobenius-Institute Frankfurt am Main

Rock Paintings from the Frobenius Collection

“The art of the twentieth century has already come under the influence of the great tradition of prehistoric rock art”

Alfred Barr, Director of the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA), 1937

In addition to the art of the “primitives” (the term used for indigenous peoples at the time) and the “naives” (children and the mentally ill), the quest for original, unspoilt forms of expression in the 1920s and ‘30s gave rise to a third, often neglected source of inspiration for the development of modern art: prehistoric art, particularly the oldest human art tradition, rock art. Around 100 samples, including many large, wall-sized copies from the Frobenius Institute, as well as photographic and archive material, depict the epic history of rock-art documentation in European caves, the central Sahara, the savannahs of Zimbabwe, and the Australian outback. This exhibition examines the impact of these never-before-seen images on modernity, and the manner in which they have inspired artists.

It also touches on the history of interpreting prehistoric rock art over the last century. The answers to the question about what prehistoric artists originally intended for their works 7,000, 10,000 or 30,000 years ago opens up perspectives on projections typical for the time in the interplay between the evolutionary/functionalistic paradigms and the postulate of deep-rooted basic anthropological dispositions.

Often found in inaccessible locations, caves or deserts, these carved or painted images were made known to a wide audience in cities across Europe and the USA in the form of large-scale painted copies. German ethnologist Leo Frobenius (1873-1938) created the world’s most prominent collection of these copies. Following his sixth trip to Africa in 1912, he began taking painters with him as copyists on his many “German Inner Africa Research Expeditions”. The famous rock art of North Africa, inner Sahara and southern Africa was all copied on site, often involving great hazards. Frobenius later also sent expeditions to European rock-art regions in Spain, France, northern Italy and Scandinavia, as well as to Indonesia and Australia. Until his death in 1938, he amassed a collection of almost 5,000 rock-art copies, in colour and usually in original size (up to 2.5 x 10 metres), which is today housed at the Frobenius Institute at Frankfurt’s Goethe University.

The almost forgotten, spectacular, international exhibition history of these images has only recently been possible to reconstruct: In the 1930s, the copies toured almost all major European cities, as well as 32 American metropolises, being displayed as part of acclaimed exhibitions at Berlin’s Reichstag, Paris’ Trocadéro and New York’s Museum of Modern Art, among others.

As early as 1937, Alfred Barr, the young founding director of the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA), was convinced that “The art of the twentieth century has already come under the influence of the great traditions of prehistoric rock art”, consequently exhibiting the rock art alongside works by artists such as Klee, Miró, Arp and Masson.

Conversely, the interest of art’s avant-garde played virtually no part in producing the rock-art copies, which were designed as transportable facsimiles, i.e. as pure scientific images, intended to help prove the cultural and historical developments of the earliest prehistory. According to Frobenius, the painters had to “adopt a level of intellectuality and spirituality befitting the past” when copying prehistoric rock art.

Nevertheless, the copyists each also blazed their own trail striking a balance between scientific documentation and artistry. They were well aware of the interest expressed by art’s avant-garde in the prehistoric images. The variety of painting techniques used, and the sometimes experimental attempts at reproducing the structure of the rocky background through colour and texture, and coping with weathered, incomplete motifs, attest to individual styles and contemporary artistic influences.

Over time, the status of the painted copies has changed, from copies, to original copies, into originals. While painting was initially the documentation method of choice since photographs could not yet be taken in colour - not to mention original size - the 1950s and ‘60s saw it become the first of many technological dead-ends in the scientific documentation of prehistoric rock art. The notion of translating 3D to 2D, coupled with their idealisation and dramatisation of motifs, meant painted rock-art copies were soon discredited as scientific images. At the same time, the painted copies increasingly and unwittingly became a unique art form of their own, and a leading fossil of a bygone science era in which art and science were combined more naturally. According to German ethnologist Mark Münzel, the images were a form of “scientific expressionism”.

The exhibition at the Martin-Gropius-Bau also highlights the interplay between art and scientific pictures in the 1920s and ‘30s, showing how copies of rock images became art, and how art was simultaneously influenced by said copies.

The numerous rock images on display spark a lively discussion on the early beginnings of art and human creativity in the contemporary art scene at the time. Some pieces clearly illustrate the effect of these exhibitions. The work of Willi Baumeister, for example, underwent a shift in style around 1929/30, adopting many of the design elements and techniques used in the rock art. The influence is subtler with other artists. While Europe’s surrealists certainly benefited greatly from interacting with prehistoric art, yet the works of Jackson Pollock also contain some allusions.

This exhibition on ancient art as a subject of research and a vital source of inspiration for modernity discusses surprisingly relevant issues.

The Kulturstiftung der Länder, Ernst von Siemens Kunststiftung and Hahn-Hissinck’sche Frobenius-Stiftung all contributed generously to restoration of the works.

ORGANIZER Berliner Festspiele / Martin-Gropius-Bau.

An exhibition run by the Frobenius Institute at the Goethe University of Frankfurt. In co-operation with the Martin-Gropius-Bau.

CURATOR Dr Richard Kuba, with the assistance of Dr Hélène Ivanoff

PARTNERS Wall, ALEXA, Visit Berlin, Dussmann

MEDIA PARTNERS Tagesspiegel, G/Geschichte, Antike Welt, National Geographic, kunst:art, Exberliner, kulturradio, Weltkunst

“The art of the twentieth century has already come under the influence of the great tradition of prehistoric rock art”

Alfred Barr, Director of the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA), 1937

In addition to the art of the “primitives” (the term used for indigenous peoples at the time) and the “naives” (children and the mentally ill), the quest for original, unspoilt forms of expression in the 1920s and ‘30s gave rise to a third, often neglected source of inspiration for the development of modern art: prehistoric art, particularly the oldest human art tradition, rock art. Around 100 samples, including many large, wall-sized copies from the Frobenius Institute, as well as photographic and archive material, depict the epic history of rock-art documentation in European caves, the central Sahara, the savannahs of Zimbabwe, and the Australian outback. This exhibition examines the impact of these never-before-seen images on modernity, and the manner in which they have inspired artists.

It also touches on the history of interpreting prehistoric rock art over the last century. The answers to the question about what prehistoric artists originally intended for their works 7,000, 10,000 or 30,000 years ago opens up perspectives on projections typical for the time in the interplay between the evolutionary/functionalistic paradigms and the postulate of deep-rooted basic anthropological dispositions.

Often found in inaccessible locations, caves or deserts, these carved or painted images were made known to a wide audience in cities across Europe and the USA in the form of large-scale painted copies. German ethnologist Leo Frobenius (1873-1938) created the world’s most prominent collection of these copies. Following his sixth trip to Africa in 1912, he began taking painters with him as copyists on his many “German Inner Africa Research Expeditions”. The famous rock art of North Africa, inner Sahara and southern Africa was all copied on site, often involving great hazards. Frobenius later also sent expeditions to European rock-art regions in Spain, France, northern Italy and Scandinavia, as well as to Indonesia and Australia. Until his death in 1938, he amassed a collection of almost 5,000 rock-art copies, in colour and usually in original size (up to 2.5 x 10 metres), which is today housed at the Frobenius Institute at Frankfurt’s Goethe University.

The almost forgotten, spectacular, international exhibition history of these images has only recently been possible to reconstruct: In the 1930s, the copies toured almost all major European cities, as well as 32 American metropolises, being displayed as part of acclaimed exhibitions at Berlin’s Reichstag, Paris’ Trocadéro and New York’s Museum of Modern Art, among others.

As early as 1937, Alfred Barr, the young founding director of the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA), was convinced that “The art of the twentieth century has already come under the influence of the great traditions of prehistoric rock art”, consequently exhibiting the rock art alongside works by artists such as Klee, Miró, Arp and Masson.

Conversely, the interest of art’s avant-garde played virtually no part in producing the rock-art copies, which were designed as transportable facsimiles, i.e. as pure scientific images, intended to help prove the cultural and historical developments of the earliest prehistory. According to Frobenius, the painters had to “adopt a level of intellectuality and spirituality befitting the past” when copying prehistoric rock art.

Nevertheless, the copyists each also blazed their own trail striking a balance between scientific documentation and artistry. They were well aware of the interest expressed by art’s avant-garde in the prehistoric images. The variety of painting techniques used, and the sometimes experimental attempts at reproducing the structure of the rocky background through colour and texture, and coping with weathered, incomplete motifs, attest to individual styles and contemporary artistic influences.

Over time, the status of the painted copies has changed, from copies, to original copies, into originals. While painting was initially the documentation method of choice since photographs could not yet be taken in colour - not to mention original size - the 1950s and ‘60s saw it become the first of many technological dead-ends in the scientific documentation of prehistoric rock art. The notion of translating 3D to 2D, coupled with their idealisation and dramatisation of motifs, meant painted rock-art copies were soon discredited as scientific images. At the same time, the painted copies increasingly and unwittingly became a unique art form of their own, and a leading fossil of a bygone science era in which art and science were combined more naturally. According to German ethnologist Mark Münzel, the images were a form of “scientific expressionism”.

The exhibition at the Martin-Gropius-Bau also highlights the interplay between art and scientific pictures in the 1920s and ‘30s, showing how copies of rock images became art, and how art was simultaneously influenced by said copies.

The numerous rock images on display spark a lively discussion on the early beginnings of art and human creativity in the contemporary art scene at the time. Some pieces clearly illustrate the effect of these exhibitions. The work of Willi Baumeister, for example, underwent a shift in style around 1929/30, adopting many of the design elements and techniques used in the rock art. The influence is subtler with other artists. While Europe’s surrealists certainly benefited greatly from interacting with prehistoric art, yet the works of Jackson Pollock also contain some allusions.

This exhibition on ancient art as a subject of research and a vital source of inspiration for modernity discusses surprisingly relevant issues.

The Kulturstiftung der Länder, Ernst von Siemens Kunststiftung and Hahn-Hissinck’sche Frobenius-Stiftung all contributed generously to restoration of the works.

ORGANIZER Berliner Festspiele / Martin-Gropius-Bau.

An exhibition run by the Frobenius Institute at the Goethe University of Frankfurt. In co-operation with the Martin-Gropius-Bau.

CURATOR Dr Richard Kuba, with the assistance of Dr Hélène Ivanoff

PARTNERS Wall, ALEXA, Visit Berlin, Dussmann

MEDIA PARTNERS Tagesspiegel, G/Geschichte, Antike Welt, National Geographic, kunst:art, Exberliner, kulturradio, Weltkunst