Germaine Krull - Photographs

15 Oct 2015 - 31 Jan 2016

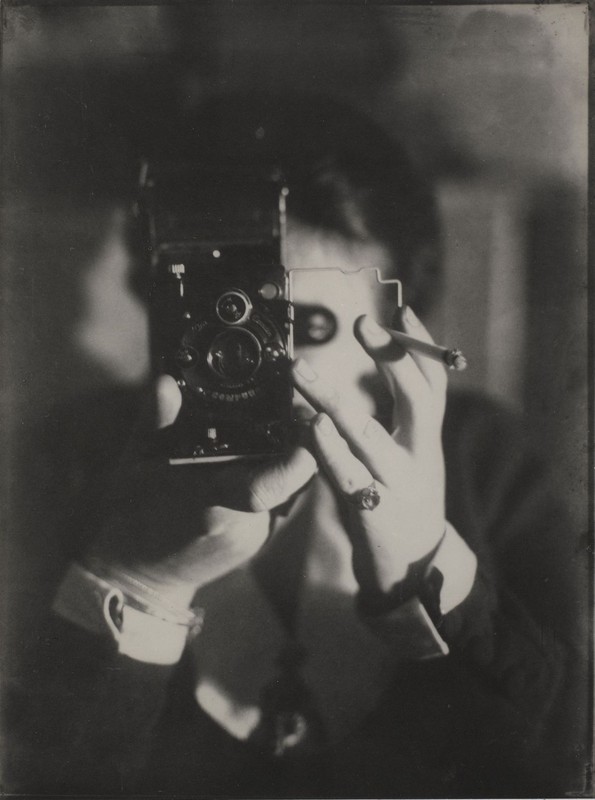

Germaine Krull: Autoportrait avec Ikarette, 1925.

Achat grâce au mécénat de Yves Rocher, 2011. Ancienne collection Christian Bouqueret. Centre Pompidou, Paris. Musée national d'art moderne/Centre de création industrielle

© Estate Germaine Krull, Museum Folkwang, Essen

Achat grâce au mécénat de Yves Rocher, 2011. Ancienne collection Christian Bouqueret. Centre Pompidou, Paris. Musée national d'art moderne/Centre de création industrielle

© Estate Germaine Krull, Museum Folkwang, Essen

In the Paris of the 1920s, Germaine Krull (1897-1985) was considered the photographer of the city’s intellectuals and an important representative of the new genre. André Malraux exhibited her photographs, putting them on a par with modern painting. Jean Cocteau said of her that, using her camera, she had “discovered a new world in which technology and the spirit infused one another”, and Walter Benjamin included her in his “Kleine Geschichte der Fotografie” [Brief History of Photography]. He esteemed her politically and humanistically committed attitude as well as her radical photographic aesthetic, and assigned her the same artistic significance as August Sander and Karl Blossfeldt. Together with the Jeu de Paume, Paris, the Martin-Gropius-Bau is dedicated a comprehensive retrospective to her.

Germaine Krull (1897-1985) made a name for herself as a unique photographic talent with a cosmopolitan biography. Born in Posen in Prussia and raised in Italy, France, and Switzerland, she began her photographic training in Munich in 1915 and opened her first photographic atelier in the city in 1917, where she took her famous portrait of Kurt Eisner, among others. After being expelled from Bavaria in the wake of the collapse of the short-lived Bavarian Soviet Republic, Germaine Krull’s left-wing activism took her to Russia, before moves to Berlin, Amsterdam, and finally – in 1925 – Paris.

In Paris, her extraordinary photographs of technical constructions, harbors, and industrial facilities brought her sudden success. She created a new type of technical photography which dispensed with spectacular visual rhetoric. With “Metal” (1928), her first published book of photographs, she joined the international photographic avant-garde. Socializing with friends such as Sonia and Robert Delaunay, Man Ray and André Kertész, she took on numerous commissions for magazines, the fashion industry, and advertising agencies. Her portraits and photographs of street life -- including a photo feature on the clochards of Paris -- are characterized by an unconventional realism which, with its unusual perspective and fragmenting image cut out, reveals the influence of the “New Vision” of the Bauhaus school.

For Benjamin, it was not her fascination with technology that made Germaine Krull's so important, but their “reproduction of reality”: in their cold mechanical functionality, frozen on glass plates, the German intellectual saw captured more of the reification of human relationships than in a simple photograph of a factory in which the workers are posing in front of their machines.

Germaine Krull’s ability to achieve with her camera a deeper understanding of reality was a product of her artistic biography: Born to German parents near the Russian border, she studied photography in Munich and soon came to share the enthusiasm of her Munich friends for revolutionary Soviet cinema.

After stops in Berlin and Amsterdam, Germaine Krull came to Paris, which remained her artistic home until the end of the Second World War. After 1945, she recognized that photography would no longer remain the intellectual and artistic adventure it has been during the interwar period. The media had lost interest in the artistic messages of the photographers; rather, photographs were in demand simply to illustrate articles.

Germaine Krull went to the Far East, initially as a photojournalist. After more than 15 years in Bangkok, she returned to Paris for exhibitions of her work. At the age of 70, she joined followers of the exiled Dalai Lama in northern India, living with them for several years in an ancient temple. Finally returning to Germany toward the end of her life, she died, largely forgotten, in Wetzlar in 1985.

ORGANIZER: Berliner Festspiele. An exhibition of the Jeu de Paume in cooperation with Berliner Festspiele / Martin-Gropius-Bau. Made possible by the Sparkasse cultural fund Sparkassen-Kulturfonds of the Deutschen Sparkassen- und Giroverbandes

PARTNERS: Wall, visit Berlin, Where Berlin, Alexa, Bouvet Ladubay

MEDIA PARTNERS: Tagesspiegel, inforadio, Monopol, Exberliner, Aviva-berlin.de, Photo International, fotoforum-Verlag, EMOTION Verlag GmbH, HOME ahead media, schwarzweiss

Germaine Krull (1897-1985) made a name for herself as a unique photographic talent with a cosmopolitan biography. Born in Posen in Prussia and raised in Italy, France, and Switzerland, she began her photographic training in Munich in 1915 and opened her first photographic atelier in the city in 1917, where she took her famous portrait of Kurt Eisner, among others. After being expelled from Bavaria in the wake of the collapse of the short-lived Bavarian Soviet Republic, Germaine Krull’s left-wing activism took her to Russia, before moves to Berlin, Amsterdam, and finally – in 1925 – Paris.

In Paris, her extraordinary photographs of technical constructions, harbors, and industrial facilities brought her sudden success. She created a new type of technical photography which dispensed with spectacular visual rhetoric. With “Metal” (1928), her first published book of photographs, she joined the international photographic avant-garde. Socializing with friends such as Sonia and Robert Delaunay, Man Ray and André Kertész, she took on numerous commissions for magazines, the fashion industry, and advertising agencies. Her portraits and photographs of street life -- including a photo feature on the clochards of Paris -- are characterized by an unconventional realism which, with its unusual perspective and fragmenting image cut out, reveals the influence of the “New Vision” of the Bauhaus school.

For Benjamin, it was not her fascination with technology that made Germaine Krull's so important, but their “reproduction of reality”: in their cold mechanical functionality, frozen on glass plates, the German intellectual saw captured more of the reification of human relationships than in a simple photograph of a factory in which the workers are posing in front of their machines.

Germaine Krull’s ability to achieve with her camera a deeper understanding of reality was a product of her artistic biography: Born to German parents near the Russian border, she studied photography in Munich and soon came to share the enthusiasm of her Munich friends for revolutionary Soviet cinema.

After stops in Berlin and Amsterdam, Germaine Krull came to Paris, which remained her artistic home until the end of the Second World War. After 1945, she recognized that photography would no longer remain the intellectual and artistic adventure it has been during the interwar period. The media had lost interest in the artistic messages of the photographers; rather, photographs were in demand simply to illustrate articles.

Germaine Krull went to the Far East, initially as a photojournalist. After more than 15 years in Bangkok, she returned to Paris for exhibitions of her work. At the age of 70, she joined followers of the exiled Dalai Lama in northern India, living with them for several years in an ancient temple. Finally returning to Germany toward the end of her life, she died, largely forgotten, in Wetzlar in 1985.

ORGANIZER: Berliner Festspiele. An exhibition of the Jeu de Paume in cooperation with Berliner Festspiele / Martin-Gropius-Bau. Made possible by the Sparkasse cultural fund Sparkassen-Kulturfonds of the Deutschen Sparkassen- und Giroverbandes

PARTNERS: Wall, visit Berlin, Where Berlin, Alexa, Bouvet Ladubay

MEDIA PARTNERS: Tagesspiegel, inforadio, Monopol, Exberliner, Aviva-berlin.de, Photo International, fotoforum-Verlag, EMOTION Verlag GmbH, HOME ahead media, schwarzweiss