Languages of Futurism

02 Oct 2009 - 11 Jan 2010

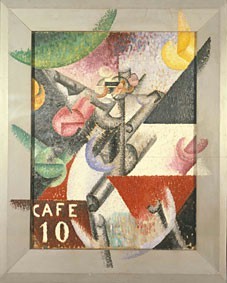

Gino Severini

Ritmo plastico del 14 luglio, 1913

Olio su tela, 66 x 50 cm

© Rovereto, Mart, collezione Severini Franchina

Ritmo plastico del 14 luglio, 1913

Olio su tela, 66 x 50 cm

© Rovereto, Mart, collezione Severini Franchina

LANGUAGES OF FUTURISM

2 October 2009 to 11 January 2010

Organizer:

Berliner Festspiele. In cooperation with Museo d’Arte Moderna e Contemporanea di Trento e Rovereto and Italienisches Kulturinstitut Berlin. Sponsored by the Embassy of the Italian Republic

Media Partners rbb Inforadio, rbb Kulturradio, rbb Fernsehen

On the occasion of the 100th anniversary of Futurism the Martin-Gropius-Bau in cooperation with the Italienisches Kulturinstitut Berlin and the Museo d’Arte Moderna e Contemporanea di Trento e Rovereto (Mart) is organizing an exhibition to pay tribute to Futurist forms of artistic expression in all their variety – from painting and architecture to literature.

The exhibition consists mainly of loans from the Mart, which has a collection of over 4,000 Futurist works, including masterpieces by Carrà, Severini, Russolo and Balla, as well as an extensive archive of documents and books by the most important representatives of the avant-garde. The museum and study centre are supplemented by the Casa Museo Depero, Italy’s first Futurist Museum that was founded by Fortunato Depero himself and opened in cooperation with the city of Rovereto in 1959.

The Berlin exhibition is intended as a presentation and a tribute to the Art-Life project, to which Futurism gave theoretical form in its manifestos and systematically put into practice by means of a programme that envisaged the participation of all the arts in the construction of a new aesthetic of everyday life.

On 20 February 1909 Filippo Tommaso Marinetti (1876–1944) had published the Futurist Manifesto in the Paris daily Le Figaro, thus founding the avant-garde art movement known as Futurism. In his eleven-point programme Marinetti propagated a new culture embracing all areas of life. His theses were directed against traditional art and glorified speed, violence and war. The words of the young writer, born in Alexandria, Egypt, unleashed a revolution that struck the most sensitive chord of the yearning for radical renewal for which Italian art had been searching.

Only a few years earlier in Milan Marinetti had founded the periodical Poesia which became the organ of those young writers who demanded a radical change in Italian literature. Now, shuttling back and forth between Paris and Milan, he brought Futurism to the whole of Europe. He shared with numerous artists the revolutionary ideas contained in the theoretical manifestos, which from 1910 onwards also bore the signatures of Umberto Boccioni, Luigi Russolo, Carlo Carrà, Gino Severini, Giacomo Balla and later of Antonio Sant’Elia, Fortunato Depero, Enrico Prampolini, Ardengo Soffici and many others, including Tullio Crali, Renato Bertelli and Ernesto Thayath.

Marinetti, unquestionably the first great master of media communication strategies, was at war – like all the painters who were close to Futurism – with the past, with history, with remembrance. Under the slashing blows of his pamphlet and theoretical manifestos the “cult objects” of the past toppled one after another.

He condemned the art of the Renaissance as he did the Tango or the music of Wagner and Spaghetti, the romanticization of Venice or love in the moonlight. The name of the movement, which was his invention, was well suited to expressing the absolute faith in the new technologies, especially the automobile and the aeroplane.

Futurism enabled the Italian art of the early twentieth century to take its place among the main avant-garde currents which already existed in Europe – especially France and Germany. With its interest in revolutionizing all the arts, from painting to architecture, from poetry to literature, from design to drama, Futurism in Italy was in one sense an artistic movement, but it was also a new way of looking at the cultural life of a country which entered the twentieth century in a state of strong social and economic backwardness and profound divisions.

The Berlin exhibition begins with an introductory section dealing with the upheavals in painting caused by the historical core group of Futurists around Boccioni, Balla, Severini, Russolo, Soffici and Carrà.

The focus of the exhibition, however, will be on the innovations that ushered in a new and extraordinarily creative epoch of Futurism after Boccioni’s death in 1916, when painters like Severini, Balla, Depero, Prampolini, Crali, to name only the best-known, succeeded with the unfailing support and consent of Filippo Tommaso Marinetti in lending new meaning to artistic acts.

They opened the way to an experimental approach to the languages of art, poetry, literature, interior design, fashion, industrial design, photography and set design, that formed the aesthetic basis for the second half of the twentieth century. The exhibition shows a selection of works which demonstrate most clearly the sense of an “extension” of the aesthetic dimension to life in general and the “blurring of the distinctions” between the various artistic disciplines.

This will give visitors the opportunity to learn something about those aspects of Futur-ism that are less well known but no less worthy of attention than the familiar manifestations of Futurism in painting.

Devoting an exhibition to Futurism in Berlin is of particular significance as this city played an important role in the Futurists’ dissemination of their revolutionary ideas in Germany thanks to the efforts of Herwarth Walden (1887–1941). In 1912 the Futurist Manifesto was published in Der Sturm, a periodical founded by Herwarth Walden and Alfred Döblin. Soon afterwards (12 April – 31 May 1912) the first Futurist exhibition in Germany was held in Walden’s eponymous gallery at Tiergartenstrasse 34 a. It had previously been on view in Paris at the Galerie Bernheim Jeune (5 – 27 February 1912) and in London at the Sackville Gallery (1 March – 4 April 1912) and showed in Berlin 35 pictures by the Futurists Umberto Boccioni, Carlo Carrà, Luigi Russolo and Gino Severini. This was followed by further Futurist appearances in Walden’s periodical and gallery, as a selection of documents in the exhibition in the Martin-Gropius-Bau make clear.

2 October 2009 to 11 January 2010

Organizer:

Berliner Festspiele. In cooperation with Museo d’Arte Moderna e Contemporanea di Trento e Rovereto and Italienisches Kulturinstitut Berlin. Sponsored by the Embassy of the Italian Republic

Media Partners rbb Inforadio, rbb Kulturradio, rbb Fernsehen

On the occasion of the 100th anniversary of Futurism the Martin-Gropius-Bau in cooperation with the Italienisches Kulturinstitut Berlin and the Museo d’Arte Moderna e Contemporanea di Trento e Rovereto (Mart) is organizing an exhibition to pay tribute to Futurist forms of artistic expression in all their variety – from painting and architecture to literature.

The exhibition consists mainly of loans from the Mart, which has a collection of over 4,000 Futurist works, including masterpieces by Carrà, Severini, Russolo and Balla, as well as an extensive archive of documents and books by the most important representatives of the avant-garde. The museum and study centre are supplemented by the Casa Museo Depero, Italy’s first Futurist Museum that was founded by Fortunato Depero himself and opened in cooperation with the city of Rovereto in 1959.

The Berlin exhibition is intended as a presentation and a tribute to the Art-Life project, to which Futurism gave theoretical form in its manifestos and systematically put into practice by means of a programme that envisaged the participation of all the arts in the construction of a new aesthetic of everyday life.

On 20 February 1909 Filippo Tommaso Marinetti (1876–1944) had published the Futurist Manifesto in the Paris daily Le Figaro, thus founding the avant-garde art movement known as Futurism. In his eleven-point programme Marinetti propagated a new culture embracing all areas of life. His theses were directed against traditional art and glorified speed, violence and war. The words of the young writer, born in Alexandria, Egypt, unleashed a revolution that struck the most sensitive chord of the yearning for radical renewal for which Italian art had been searching.

Only a few years earlier in Milan Marinetti had founded the periodical Poesia which became the organ of those young writers who demanded a radical change in Italian literature. Now, shuttling back and forth between Paris and Milan, he brought Futurism to the whole of Europe. He shared with numerous artists the revolutionary ideas contained in the theoretical manifestos, which from 1910 onwards also bore the signatures of Umberto Boccioni, Luigi Russolo, Carlo Carrà, Gino Severini, Giacomo Balla and later of Antonio Sant’Elia, Fortunato Depero, Enrico Prampolini, Ardengo Soffici and many others, including Tullio Crali, Renato Bertelli and Ernesto Thayath.

Marinetti, unquestionably the first great master of media communication strategies, was at war – like all the painters who were close to Futurism – with the past, with history, with remembrance. Under the slashing blows of his pamphlet and theoretical manifestos the “cult objects” of the past toppled one after another.

He condemned the art of the Renaissance as he did the Tango or the music of Wagner and Spaghetti, the romanticization of Venice or love in the moonlight. The name of the movement, which was his invention, was well suited to expressing the absolute faith in the new technologies, especially the automobile and the aeroplane.

Futurism enabled the Italian art of the early twentieth century to take its place among the main avant-garde currents which already existed in Europe – especially France and Germany. With its interest in revolutionizing all the arts, from painting to architecture, from poetry to literature, from design to drama, Futurism in Italy was in one sense an artistic movement, but it was also a new way of looking at the cultural life of a country which entered the twentieth century in a state of strong social and economic backwardness and profound divisions.

The Berlin exhibition begins with an introductory section dealing with the upheavals in painting caused by the historical core group of Futurists around Boccioni, Balla, Severini, Russolo, Soffici and Carrà.

The focus of the exhibition, however, will be on the innovations that ushered in a new and extraordinarily creative epoch of Futurism after Boccioni’s death in 1916, when painters like Severini, Balla, Depero, Prampolini, Crali, to name only the best-known, succeeded with the unfailing support and consent of Filippo Tommaso Marinetti in lending new meaning to artistic acts.

They opened the way to an experimental approach to the languages of art, poetry, literature, interior design, fashion, industrial design, photography and set design, that formed the aesthetic basis for the second half of the twentieth century. The exhibition shows a selection of works which demonstrate most clearly the sense of an “extension” of the aesthetic dimension to life in general and the “blurring of the distinctions” between the various artistic disciplines.

This will give visitors the opportunity to learn something about those aspects of Futur-ism that are less well known but no less worthy of attention than the familiar manifestations of Futurism in painting.

Devoting an exhibition to Futurism in Berlin is of particular significance as this city played an important role in the Futurists’ dissemination of their revolutionary ideas in Germany thanks to the efforts of Herwarth Walden (1887–1941). In 1912 the Futurist Manifesto was published in Der Sturm, a periodical founded by Herwarth Walden and Alfred Döblin. Soon afterwards (12 April – 31 May 1912) the first Futurist exhibition in Germany was held in Walden’s eponymous gallery at Tiergartenstrasse 34 a. It had previously been on view in Paris at the Galerie Bernheim Jeune (5 – 27 February 1912) and in London at the Sackville Gallery (1 March – 4 April 1912) and showed in Berlin 35 pictures by the Futurists Umberto Boccioni, Carlo Carrà, Luigi Russolo and Gino Severini. This was followed by further Futurist appearances in Walden’s periodical and gallery, as a selection of documents in the exhibition in the Martin-Gropius-Bau make clear.