The British View: Germany – Memories of a Nation

08 Oct 2016 - 09 Jan 2017

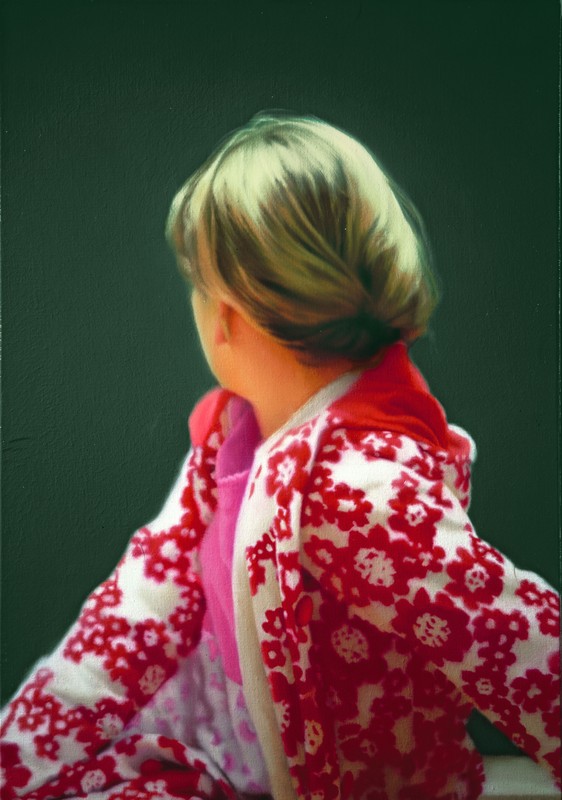

Gerhard Richter

Betty (Edition 23/25), 1991

Offsetdruck auf Karton, 97,1 x 66,2 cm

Sammlung Olbricht

© Atelier Gerhard Richter

Betty (Edition 23/25), 1991

Offsetdruck auf Karton, 97,1 x 66,2 cm

Sammlung Olbricht

© Atelier Gerhard Richter

Germany? But where is it?

I cannot find the country

Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, 1796

On 9 November 1989, media all over the world reported on the fall of the Berlin Wall – an event that gave rise to a new, united Germany. Today, this Germany plays an important role in world affairs. For decades, citizens in East and West Germany lived under different political systems, but they had many deep-rooted memories in common.

This exhibition explores some of these memories on the basis of approximately 200 objects that originated during the last 600 years in Germany, and which are formative for culture, business and politics – past and present. They tell stories of great German achievements, of philosophers, poets and artists, and of historical events that have shaped the face of Germany today. A nation that has emerged in the shadow of the most terrible memory of all, the Holocaust.

There are memories that are well known, and others that have yet to be discovered or newly rediscovered. The selected works often tell several stories and paint a nuanced picture of Germany’s complex history. Using high-profile museum pieces and historical documents, the exhibition’s five chapters outline, in thematic and chronological jumps, how Germany ultimately became what it is today:

Germany - Memories of a Nation

Fluid borders

Empire and Nation

Made in Germany

Crisis and Remembrance

The exhibition begins and ends with the year 1989 and Gerhard Richter’s Betty from 1991, who is glancing back.

Valuable works are on display, such as Albrecht Dürer’s 1515 woodcut of a rhinoceros and the 1730 porcelain version of Johann Gottlieb Kirchner, which was based on a template from Dürer. They represent two of the most valuable technological and artistic achievements of the German world: modern printing and the invention of porcelain. Porcelain was re-invented in the early 18th century in Meißen. It became an important European industry and proved competition to China’s “white gold”. The grandiose Nuremberg Chronicle from 1493 reflects the introduction of the print, which was invented by Johannes Gutenberg in the 15th century. Through this invention, knowledge and art would easily be disseminated throughout Europe.

The astrolabe of 1596 displays German precision and the highest standards in gold work. Skilful German metal craftsmen built some of the best scientific instruments of Early Modern times. Johann Anton Linden was one of them. His astronomical compendium is as big as an eBook reader – and is a world time clock and GPS in one. An aphorism is engraved: “Time is running out. Death is like a threshold that you have to cross.”

One of the most impressive objects of the exhibition is Ernst Barlach’s bronze sculpture, entitled The Floater (“Schwebender”). It's an angel in another form: the mouth and eyes are closed, the wings are folded, the gaze directed inward. Barlach (1870-1937) created it in 1926 on behalf of Güstrower Church Council as a war memorial for the 700th anniversary of the cathedral. The face is reminiscent of the artist Käthe Kollwitz, who lost her son in the war in October 1914. It represents the pain of all mothers.

Barlach enthusiastically enlisted himself for military service in 1915. He came back a pacifist. In 1933, the Nazis removed his sculptures from public spaces. He was considered a “degenerate” artist; because his style had nothing to do with heroism. In August 1937, the angel was removed from the cathedral, brought to Schwerin and melted down in 1940 for the war effort. The plaster mould was saved, and a second recast was made and hidden in a village near Lüneburg. In 1951, the angel was meant to be issued again. However, Güstrow was in East Germany, 160 km from Berlin. The Cold War was in full swing. It was also unclear how the GDR would deal with Barlach’s art, so the cast was issued in Cologne’s Antoniterkirche. It wasn’t until 1953 that a faithful cast for the Güstrow Cathedral was made. On 13 December 1981, Helmut Schmidt, former Chancellor of Germany, and Erich Honecker, then General Secretary of the East German Socialist Unity Party of Germany, visited Barlach’s angel in the cathedral in an official state visit. For both heads of state, the angel represented a common memory.

In 1937, the Buchenwald concentration camp was built at the gates of Weimar – the city of Goethe and Schiller, of Bauhaus, and the cradle of the democratic constitution of the Weimar Republic. According to estimates, approximately 56,000 people died there by 1945. The camp gate of Buchenwald was built in 1938. It bears the inscription “To each his own”. It was designed by Franz Ehrlich, former Bauhaus student who was detained in the Buchenwald concentration camp. The signature is attached and legible from the inside. The prisoners would have had the inscription constantly before their eyes. The inscription hearkens back to the two-thousand-year old Roman legal principle: “To live honourably, to hurt no one, to give each his own [suum cuique]”.

Twelve years of Nazi terror counts as one of Germany’s central, inescapable memories. The years led to the systematic murder of six million Jews and brought death and destruction throughout Europe.

Many artists, including Georg Baselitz, process this time again and again in their work. In his 1977 etching “Eagle”, the German eagle and the flag of democratic Germany are worn and frayed and upside down; a reflection perhaps on the fragility of these ideals.

The exhibition traces German identity from a British perspective. The result is a dialogue between Germany and its history.

A British Museum exhibition. Curator: Barrie Cook, historian at the British Museum. Initiated by Neil MacGregor, former Director at the British Museum, London, and created on the basis of his Beck-Verlag book.

The Martin-Gropius-Bau is grateful to the Federal Government Commissioner for Culture and Media, whose funding made this exhibition possible, as well as the German Historical Museum and the Berlin State Museums for the generous loaning of items; to the Friede Springer Foundation for the generous support of the education programme.

ORGANIZER Berliner Festspiele / Martin-Gropius-Bau. An exhibition of the British Museum accompanied by a book of Neil MacGregor.

I cannot find the country

Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, 1796

On 9 November 1989, media all over the world reported on the fall of the Berlin Wall – an event that gave rise to a new, united Germany. Today, this Germany plays an important role in world affairs. For decades, citizens in East and West Germany lived under different political systems, but they had many deep-rooted memories in common.

This exhibition explores some of these memories on the basis of approximately 200 objects that originated during the last 600 years in Germany, and which are formative for culture, business and politics – past and present. They tell stories of great German achievements, of philosophers, poets and artists, and of historical events that have shaped the face of Germany today. A nation that has emerged in the shadow of the most terrible memory of all, the Holocaust.

There are memories that are well known, and others that have yet to be discovered or newly rediscovered. The selected works often tell several stories and paint a nuanced picture of Germany’s complex history. Using high-profile museum pieces and historical documents, the exhibition’s five chapters outline, in thematic and chronological jumps, how Germany ultimately became what it is today:

Germany - Memories of a Nation

Fluid borders

Empire and Nation

Made in Germany

Crisis and Remembrance

The exhibition begins and ends with the year 1989 and Gerhard Richter’s Betty from 1991, who is glancing back.

Valuable works are on display, such as Albrecht Dürer’s 1515 woodcut of a rhinoceros and the 1730 porcelain version of Johann Gottlieb Kirchner, which was based on a template from Dürer. They represent two of the most valuable technological and artistic achievements of the German world: modern printing and the invention of porcelain. Porcelain was re-invented in the early 18th century in Meißen. It became an important European industry and proved competition to China’s “white gold”. The grandiose Nuremberg Chronicle from 1493 reflects the introduction of the print, which was invented by Johannes Gutenberg in the 15th century. Through this invention, knowledge and art would easily be disseminated throughout Europe.

The astrolabe of 1596 displays German precision and the highest standards in gold work. Skilful German metal craftsmen built some of the best scientific instruments of Early Modern times. Johann Anton Linden was one of them. His astronomical compendium is as big as an eBook reader – and is a world time clock and GPS in one. An aphorism is engraved: “Time is running out. Death is like a threshold that you have to cross.”

One of the most impressive objects of the exhibition is Ernst Barlach’s bronze sculpture, entitled The Floater (“Schwebender”). It's an angel in another form: the mouth and eyes are closed, the wings are folded, the gaze directed inward. Barlach (1870-1937) created it in 1926 on behalf of Güstrower Church Council as a war memorial for the 700th anniversary of the cathedral. The face is reminiscent of the artist Käthe Kollwitz, who lost her son in the war in October 1914. It represents the pain of all mothers.

Barlach enthusiastically enlisted himself for military service in 1915. He came back a pacifist. In 1933, the Nazis removed his sculptures from public spaces. He was considered a “degenerate” artist; because his style had nothing to do with heroism. In August 1937, the angel was removed from the cathedral, brought to Schwerin and melted down in 1940 for the war effort. The plaster mould was saved, and a second recast was made and hidden in a village near Lüneburg. In 1951, the angel was meant to be issued again. However, Güstrow was in East Germany, 160 km from Berlin. The Cold War was in full swing. It was also unclear how the GDR would deal with Barlach’s art, so the cast was issued in Cologne’s Antoniterkirche. It wasn’t until 1953 that a faithful cast for the Güstrow Cathedral was made. On 13 December 1981, Helmut Schmidt, former Chancellor of Germany, and Erich Honecker, then General Secretary of the East German Socialist Unity Party of Germany, visited Barlach’s angel in the cathedral in an official state visit. For both heads of state, the angel represented a common memory.

In 1937, the Buchenwald concentration camp was built at the gates of Weimar – the city of Goethe and Schiller, of Bauhaus, and the cradle of the democratic constitution of the Weimar Republic. According to estimates, approximately 56,000 people died there by 1945. The camp gate of Buchenwald was built in 1938. It bears the inscription “To each his own”. It was designed by Franz Ehrlich, former Bauhaus student who was detained in the Buchenwald concentration camp. The signature is attached and legible from the inside. The prisoners would have had the inscription constantly before their eyes. The inscription hearkens back to the two-thousand-year old Roman legal principle: “To live honourably, to hurt no one, to give each his own [suum cuique]”.

Twelve years of Nazi terror counts as one of Germany’s central, inescapable memories. The years led to the systematic murder of six million Jews and brought death and destruction throughout Europe.

Many artists, including Georg Baselitz, process this time again and again in their work. In his 1977 etching “Eagle”, the German eagle and the flag of democratic Germany are worn and frayed and upside down; a reflection perhaps on the fragility of these ideals.

The exhibition traces German identity from a British perspective. The result is a dialogue between Germany and its history.

A British Museum exhibition. Curator: Barrie Cook, historian at the British Museum. Initiated by Neil MacGregor, former Director at the British Museum, London, and created on the basis of his Beck-Verlag book.

The Martin-Gropius-Bau is grateful to the Federal Government Commissioner for Culture and Media, whose funding made this exhibition possible, as well as the German Historical Museum and the Berlin State Museums for the generous loaning of items; to the Friede Springer Foundation for the generous support of the education programme.

ORGANIZER Berliner Festspiele / Martin-Gropius-Bau. An exhibition of the British Museum accompanied by a book of Neil MacGregor.