Muntean/Rosenblum

26 May - 15 Jul 2007

Self-portrait with a Second Self

In romantic stories, a letter in a bottle cast into the sea always found its addressee. Adventurous stories entrusted to the sea were written down by people who believed in the uniqueness of their experiences and wanted to share them with others. Chance is the best messenger, working twenty-four hours a day, also on Sundays and holidays, and it is never late. Today, chance does not happen, and oceans are full of bottled letters that nobody picks up.

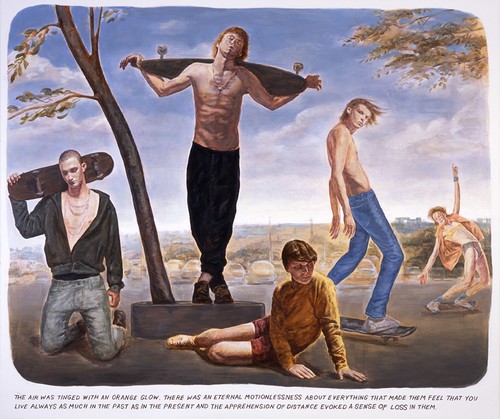

Muntean/Rosenblum paintings are very fresco and very secco. Dry fresco is a less permanent technique than true fresco. Contemporary painting exists against a background of fleeting, changeable commercial images, which is why it appropriates their conventions, themes, motifs and sometimes imitates their aims. The risk is substantial: a simulation strategy threatens to successfully introduce the false coin of contemporary painting into non-artistic transactions belonging to the general economy of images. Attempted validation of the literal sense of a painting is traditionally a threat, and today primarily a temptation. In Muntean/Rosenblum paintings, like in pictures in illustrated magazines - which today become magazines of illustrations, with text on a permanent defensive - young people receive their one-thirtieth of a second when the flash lamp illuminates them day and night. A split second is not much, too little to utter anything more than a generalised emotion, an expression of fear, joy, sadness or delight. The paintings play a game with comics: on the white rectangle of stretched canvas there appears a smaller rectangle with rounded corners, filled with colour. Here the drama has been, and will be, played; so far we’re in an interval. There is a caption at the bottom of the painting: a text written by hand, with capital letters, which we expect to provide an explanation for the painting, but which offers another riddle instead, or gives a clue that leads to nowhere. The surprising thing is that we are not surprised. The images in Muntean/Rosenblum paintings are positioned like ‘clouds’ above enigmatic texts, English-language samples of decontextualised quotations, representing in an ironic way a pretence of universal knowledge; they themselves contain texts of commonly understood and specific messages – Guess, Gap, Elvis, Evil – printed on the subjects’ T-shirts and sweatshirts.

Muntean/Rosenblum, an author doubled, present to the viewer a gallery of ordinary characters defined by style, uniform and pose. Their paintings have a slightly arousing and tranquillising effect, like a well-composed batch of medicine. Colours are whitewashed, applied with light strokes, shoulders and eye whites have the texture of gypsum as if the white background showed through. In the evenly diffused light, no substantial difference between persons, clothes and objects can be told. Some people seem to dance, others hug trees, run, or are plunged in despair, each gesture finds its visual counterbalance and the tension ultimately subsides to zero. Similarly insensible, cool and undifferentiated are the backgrounds and things that the protagonists surround themselves with: refrigerators, sofas, small carpets, bottles, fast-food packaging, construction tools, household appliances, bags, eyewear, and other accessories. But above all, trainer footwear is the strongest fetish here. Labour has disappeared from the world, tools are never shown in use, and are likely to be produced in the industrial buildings visible in the background of the painting, never in the front. This is the present time, the capitalistic obviousness, where leisure and a sense of relative wellbeing form a homogenous whole, and where lack of involvement is well received. Muntean/Rosenblum paint an epic portrait of the generation of the ‘stuffed men, leaning together,’ who embody the boring eternity, guaranteed by the quality of clothing and a reduced repertoire of manners: lean on, go past, dance near, run to, take a break after, exist only in changing relations whose course is determined by fuzzy rules, coded in the soft drone of ads, club music, conversations without aggression and meetings without significance.

Adam Szymczyk, Translated from Polish by Marcin Wawrzynczak

In romantic stories, a letter in a bottle cast into the sea always found its addressee. Adventurous stories entrusted to the sea were written down by people who believed in the uniqueness of their experiences and wanted to share them with others. Chance is the best messenger, working twenty-four hours a day, also on Sundays and holidays, and it is never late. Today, chance does not happen, and oceans are full of bottled letters that nobody picks up.

Muntean/Rosenblum paintings are very fresco and very secco. Dry fresco is a less permanent technique than true fresco. Contemporary painting exists against a background of fleeting, changeable commercial images, which is why it appropriates their conventions, themes, motifs and sometimes imitates their aims. The risk is substantial: a simulation strategy threatens to successfully introduce the false coin of contemporary painting into non-artistic transactions belonging to the general economy of images. Attempted validation of the literal sense of a painting is traditionally a threat, and today primarily a temptation. In Muntean/Rosenblum paintings, like in pictures in illustrated magazines - which today become magazines of illustrations, with text on a permanent defensive - young people receive their one-thirtieth of a second when the flash lamp illuminates them day and night. A split second is not much, too little to utter anything more than a generalised emotion, an expression of fear, joy, sadness or delight. The paintings play a game with comics: on the white rectangle of stretched canvas there appears a smaller rectangle with rounded corners, filled with colour. Here the drama has been, and will be, played; so far we’re in an interval. There is a caption at the bottom of the painting: a text written by hand, with capital letters, which we expect to provide an explanation for the painting, but which offers another riddle instead, or gives a clue that leads to nowhere. The surprising thing is that we are not surprised. The images in Muntean/Rosenblum paintings are positioned like ‘clouds’ above enigmatic texts, English-language samples of decontextualised quotations, representing in an ironic way a pretence of universal knowledge; they themselves contain texts of commonly understood and specific messages – Guess, Gap, Elvis, Evil – printed on the subjects’ T-shirts and sweatshirts.

Muntean/Rosenblum, an author doubled, present to the viewer a gallery of ordinary characters defined by style, uniform and pose. Their paintings have a slightly arousing and tranquillising effect, like a well-composed batch of medicine. Colours are whitewashed, applied with light strokes, shoulders and eye whites have the texture of gypsum as if the white background showed through. In the evenly diffused light, no substantial difference between persons, clothes and objects can be told. Some people seem to dance, others hug trees, run, or are plunged in despair, each gesture finds its visual counterbalance and the tension ultimately subsides to zero. Similarly insensible, cool and undifferentiated are the backgrounds and things that the protagonists surround themselves with: refrigerators, sofas, small carpets, bottles, fast-food packaging, construction tools, household appliances, bags, eyewear, and other accessories. But above all, trainer footwear is the strongest fetish here. Labour has disappeared from the world, tools are never shown in use, and are likely to be produced in the industrial buildings visible in the background of the painting, never in the front. This is the present time, the capitalistic obviousness, where leisure and a sense of relative wellbeing form a homogenous whole, and where lack of involvement is well received. Muntean/Rosenblum paint an epic portrait of the generation of the ‘stuffed men, leaning together,’ who embody the boring eternity, guaranteed by the quality of clothing and a reduced repertoire of manners: lean on, go past, dance near, run to, take a break after, exist only in changing relations whose course is determined by fuzzy rules, coded in the soft drone of ads, club music, conversations without aggression and meetings without significance.

Adam Szymczyk, Translated from Polish by Marcin Wawrzynczak