Americana: Mississippi

03 - 21 Nov 2009

AMERICANA: MISSISSIPPI

That's All Right

Mary Augustine Gallery | Nov. 3–21, 2009

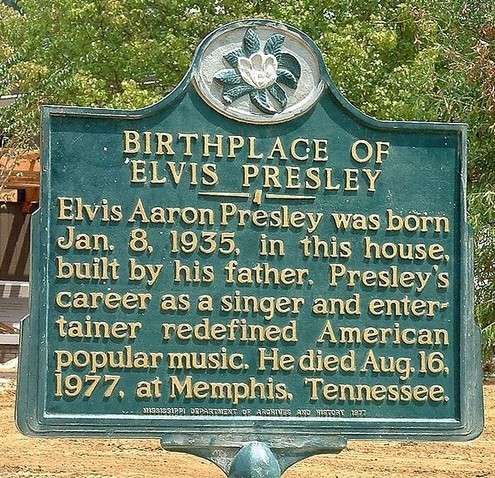

On July 5, 1954 a truck driver named Elvis Aaron Presley from Tupelo, Mississippi came into Sun Records and recorded a song titled, "That's All Right." Presley's first single was released just fourteen days later. Listeners enthusiastically called into Memphis, Tennessee radio stations wanting to know more. Meanwhile, Arthur "Big Boy" Crudup, the original performer of "That's All Right, Mama", had quit the music business after years of failing to make a living as a blues musician. Although Crudup was credited for writing "That's All Right, Mama" seven years prior, he never received any royalties; while Presley's career took off to unprecedented success. Presley's version of "That's All Right" was a dramatic revival of Crudup's song, borrowing elements from western swing. It became one of the earliest Rockabilly songs and radically changed the landscape of popular American music.

The wildly different career trajectories of Crudup and Presley present a fascinating case of the origins of rock and roll music as well as the role of race in its development. The blending of blues and country was a potent and even controversial move in a time when segregation carried onto radio airwaves. Early rock musician Bill Haley stated, "[a white artist singing] rhythm and blues was not accepted. Race music was race music and rhythm and blues was one field and country and western was another." Yet Sun Records owner Sam Phillips believed that a crossover could be achieved, and actively looked for a white singer with a "special sound." He found that in Presley, a young man heavily influenced by the blues: "down in Tupelo, Mississippi, I used to hear old Arthur Crudup bang his box the way I do now, and said if I ever got to the place I could feel what old Arthur felt, I'd be a music man like nobody ever saw."

Presley's invigorating version of "That's All Right" would set off his meteoric rise to become one of America's most recognized musicians. His reverence for the blues was evident in his frequent covers of Delta Blues songs. While often accused of appropriating the blues and "[making] Southern music more packaged, more homogenized," this view simplifies the complex relationship race and class played in the regional origins of rock music. Yet it remains a site for contention, as many of the artists Presley covered (including Crudup) did not receive the widespread recognition Presley did. This exhibition explores these questions of race and covers by presenting Crudup's original version alongside Presley's revival, comparing and contrasting the two versions. Perhaps the issue is not simply that of a white artist covering a black artist, but of translation of blending diverse musical styles to create rock music.

Curated by Jacqueline Im

That's All Right

Mary Augustine Gallery | Nov. 3–21, 2009

On July 5, 1954 a truck driver named Elvis Aaron Presley from Tupelo, Mississippi came into Sun Records and recorded a song titled, "That's All Right." Presley's first single was released just fourteen days later. Listeners enthusiastically called into Memphis, Tennessee radio stations wanting to know more. Meanwhile, Arthur "Big Boy" Crudup, the original performer of "That's All Right, Mama", had quit the music business after years of failing to make a living as a blues musician. Although Crudup was credited for writing "That's All Right, Mama" seven years prior, he never received any royalties; while Presley's career took off to unprecedented success. Presley's version of "That's All Right" was a dramatic revival of Crudup's song, borrowing elements from western swing. It became one of the earliest Rockabilly songs and radically changed the landscape of popular American music.

The wildly different career trajectories of Crudup and Presley present a fascinating case of the origins of rock and roll music as well as the role of race in its development. The blending of blues and country was a potent and even controversial move in a time when segregation carried onto radio airwaves. Early rock musician Bill Haley stated, "[a white artist singing] rhythm and blues was not accepted. Race music was race music and rhythm and blues was one field and country and western was another." Yet Sun Records owner Sam Phillips believed that a crossover could be achieved, and actively looked for a white singer with a "special sound." He found that in Presley, a young man heavily influenced by the blues: "down in Tupelo, Mississippi, I used to hear old Arthur Crudup bang his box the way I do now, and said if I ever got to the place I could feel what old Arthur felt, I'd be a music man like nobody ever saw."

Presley's invigorating version of "That's All Right" would set off his meteoric rise to become one of America's most recognized musicians. His reverence for the blues was evident in his frequent covers of Delta Blues songs. While often accused of appropriating the blues and "[making] Southern music more packaged, more homogenized," this view simplifies the complex relationship race and class played in the regional origins of rock music. Yet it remains a site for contention, as many of the artists Presley covered (including Crudup) did not receive the widespread recognition Presley did. This exhibition explores these questions of race and covers by presenting Crudup's original version alongside Presley's revival, comparing and contrasting the two versions. Perhaps the issue is not simply that of a white artist covering a black artist, but of translation of blending diverse musical styles to create rock music.

Curated by Jacqueline Im