Belle Vue

04 Feb - 13 Mar 2010

BELLE VUE

Curated by: Katerina Nikou, Thanos Stathopoulos

04.02.2010 – 13.03.2010

Belle Vue, a group show curated by Katerina Nikou and Thanos Stathopoulos opens on Thursday, 4th February 2010, at 19:30, at the Ileana Tounta Contemporary Art Center.

The show will run until 13th March 2010.

Participating artists: Dimitris Baboulis, Manolis Baboussis, Katerina Christides, Maria Friberg, Maurice Ganis, Giorgos Gyparakis, Alexandros Psychoulis, Dimitris Tataris.

“(...) two professors, close friends, from the University of Göttingen, who had been staying in Heiligenstadt, had reached the spot in front of the telescope, which is mounted above the glacier. Skeptics though they were, they could not fail to be impressed by the unique beauty of the mountains, as they had constantly assured one another, and when they arrived at the spot where the telescope was mounted, one of the them kept asking the other to be the first to look through the telescope, so as to avoid being reproached by the other for pushing himself forward in order to look through the telescope first. Finally they agreed that the older and more cultivated and, in the nature of things, the most courteous, should take the first look through the telescope, and he was overcome by what he saw. However, when his colleague approached the telescope, he had hardly put his eye to it when he gave a shrill cry and dropped dead. To this day, the friend of the man who died in this remarkable way still wonders, in the nature of things, what his colleague actually saw in the telescope, for he certainly did not see the same thing.” (Thomas Bernhard, “Beautiful View”, in The Voice Imitator, translated by Kenneth J. Northcott)

Eight artists present their own “beautiful view” of reality.

Rough and gentle, menacing or enchanting, eerie, disturbed, ironical and gloomy, startling and disquieting, this view both reveals and mocks the image of the world and of things within it.

Maurice Ganis traps his personal version of a contemporary circus inside a transparent box (model). Making explicit reference to pop culture (the band seems to have stepped directly out of the 60s, carrying something of the age’s spirit of innocence though existing in a nondescript landscape), he probes the possibility of creating an entirely utopian space: faceless, stylized men in their yellow tuxedos play music like proper wind-up toys. These yellow-clad humanoid figures (representing a peculiar form of abstract expressionism and recalling a similar strand in digital film), much like the female figures peopling the illusory space of Ganis’ painting add, create the sense of a party-in-progress: the music we fail to hear (for no music is heard) freezes the image in some unknown time.

In Giorgos Gyparakis’ Siren snapshots of a dancer suspended above the stage while performing a sensual dance in an oriental-themed club in Thessaloniki blend with footage from military air shows. Juxtaposition of these disparate images of “flying” results in a game of risky fascination and seduction. Virtual aerial combats (lovers’ squabbles?), aircraft flying in bold and exciting formations, erotic dancing and the pervasive sense of provocation lend the narrative an added dramatic edge, leading the relationship between its various elements into a climax. The music of Maurice Ravel’s Shéhérazade conjures up the elements of the myth: love, faith, allure, revenge, the world’s transient nature, mortality, the finite, time-bound nature of the narrative, and, by extension, of existence itself.

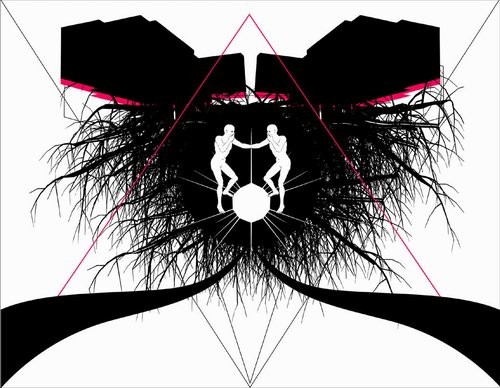

Two figures of indeterminate gender behold each other in amazement in Dimitris Baboulis’ fragile Monument to the Lack of Light. Whether an expression of some personal sense of distress, or one of disquiet generated by their relationship to their surroundings, the fact that the two figures are seen to hover in space infuses the work with a metaphysical quality. The work’s binary universe references the rift between the social and the individual; the battle between the internal and the external in what is the essential duality of nature; the possibility that the collective might coexist with the personal (or perhaps the impossibility thereof).

While on a trip to Brazil Manolis Baboussis photographed the storage rooms of one of Rio de Janeiro’s many Carnival (Samba) Schools. In the artist’s photographs, these spaces that possess an intrinsic power, not least because of the bizarre, carnival-like character of their contents, seem to erupt before one’s eyes into a singular vision, a metaphor for an uncanny world that has been “stored” out of sight: reality, the natural and the unnatural, the hallucinatory and the grotesque, absence and confinement, all blend to create an otherworldly iconography, which nonetheless documents something that is entirely real; an existing part of this world. The image, fascinating and at once disquieting, illusory, captures the frazzle of this dismantled, ghostly “circus”; of this stillborn ecstasy that is the carnival. A vague sense of sadness (or is it threat?) lurks in the beautiful view of high-rise buildings towering above a screen of tropical vegetation.

Dimitris Tataris’ continued investigations into the mutant spaces of what he calls the “domestic circus” (in the artist’s own words, “all that resides, develops and grows within the range of one’s perception of the world”) are part of a larger narrative that insists on revisiting the notions of fragility and confinement, of arrogance, fear and death, of taming, humanizing nature. In works that bear such characteristic titles as Very Fragile (a reference to the title of his first solo exhibition, Fragile [2008]) and Domestic Circus, a video-and-sound installation, the artist fills a cardboard box (an allegorical “ark”) with fragments of a delicate, unhinged, misshapen world (bones, body parts, pieces of wood, cages, birds, muzzles, the intertwined forms of animals and humans, eyeballs) – it is a view into an inner reality of ruin, desolation and enforcement, where the artist’s persona is at once that of predator and prey, victim and victimizer.

In her video Blown Out, Maria Friberg attempts to foreground the mind’s characteristic tendency to waver and contradict itself. In slow, seemingly eternal motion, a man battles with intimacy and estrangement, with pleasure and pain, with suffering, power and dependence. Still, although he struggles with such antagonistic emotions, he seems to be accepting his isolation and to be at ease with himself. The image of the sea and the waves (a miniature of the outside world) is symbolic of the fear inspired by the likelihood of abandoning ourselves, of yielding, to something much larger than us, be that love, passion, or death.

Katerina Christides’ large scale works aim to transfix viewers, to ensnare them inside their web of narrative that is highly idiosyncratic, both conceptually and in terms of design. The hybrid figures depicted in her curiously genderless portraits inhabit a remote, eerie world, inaccessible and decidedly unfamiliar. They seem caught in a state of psychological uncertainty, grappling with introspection at the same time that they try in vain to conform to a closed structure. Basically, the familiar becomes unfamiliar and the closed form opens up.

Alexandros Psychoulis uses himself, members of his family and of the extended circle of his friends as the heroes of Endless Happiness, where they are seen to endlessly urinate in some non-space. The irony here is obvious: his morbid take on the idea of “happiness” is, on the one hand, a direct, biting comment on the sheer, almost paralytic pleasure one experiences when simply satisfying their bodily functions and, on the other, a brooding reminder of the loss, or implausibility, of happiness. In the end, the image of collective relief, complemented by the irony of the work’s title, only serves to anatomize the universality of suffering.

Katerina Nikou, Thanos Stathopoulos

Curated by: Katerina Nikou, Thanos Stathopoulos

04.02.2010 – 13.03.2010

Belle Vue, a group show curated by Katerina Nikou and Thanos Stathopoulos opens on Thursday, 4th February 2010, at 19:30, at the Ileana Tounta Contemporary Art Center.

The show will run until 13th March 2010.

Participating artists: Dimitris Baboulis, Manolis Baboussis, Katerina Christides, Maria Friberg, Maurice Ganis, Giorgos Gyparakis, Alexandros Psychoulis, Dimitris Tataris.

“(...) two professors, close friends, from the University of Göttingen, who had been staying in Heiligenstadt, had reached the spot in front of the telescope, which is mounted above the glacier. Skeptics though they were, they could not fail to be impressed by the unique beauty of the mountains, as they had constantly assured one another, and when they arrived at the spot where the telescope was mounted, one of the them kept asking the other to be the first to look through the telescope, so as to avoid being reproached by the other for pushing himself forward in order to look through the telescope first. Finally they agreed that the older and more cultivated and, in the nature of things, the most courteous, should take the first look through the telescope, and he was overcome by what he saw. However, when his colleague approached the telescope, he had hardly put his eye to it when he gave a shrill cry and dropped dead. To this day, the friend of the man who died in this remarkable way still wonders, in the nature of things, what his colleague actually saw in the telescope, for he certainly did not see the same thing.” (Thomas Bernhard, “Beautiful View”, in The Voice Imitator, translated by Kenneth J. Northcott)

Eight artists present their own “beautiful view” of reality.

Rough and gentle, menacing or enchanting, eerie, disturbed, ironical and gloomy, startling and disquieting, this view both reveals and mocks the image of the world and of things within it.

Maurice Ganis traps his personal version of a contemporary circus inside a transparent box (model). Making explicit reference to pop culture (the band seems to have stepped directly out of the 60s, carrying something of the age’s spirit of innocence though existing in a nondescript landscape), he probes the possibility of creating an entirely utopian space: faceless, stylized men in their yellow tuxedos play music like proper wind-up toys. These yellow-clad humanoid figures (representing a peculiar form of abstract expressionism and recalling a similar strand in digital film), much like the female figures peopling the illusory space of Ganis’ painting add, create the sense of a party-in-progress: the music we fail to hear (for no music is heard) freezes the image in some unknown time.

In Giorgos Gyparakis’ Siren snapshots of a dancer suspended above the stage while performing a sensual dance in an oriental-themed club in Thessaloniki blend with footage from military air shows. Juxtaposition of these disparate images of “flying” results in a game of risky fascination and seduction. Virtual aerial combats (lovers’ squabbles?), aircraft flying in bold and exciting formations, erotic dancing and the pervasive sense of provocation lend the narrative an added dramatic edge, leading the relationship between its various elements into a climax. The music of Maurice Ravel’s Shéhérazade conjures up the elements of the myth: love, faith, allure, revenge, the world’s transient nature, mortality, the finite, time-bound nature of the narrative, and, by extension, of existence itself.

Two figures of indeterminate gender behold each other in amazement in Dimitris Baboulis’ fragile Monument to the Lack of Light. Whether an expression of some personal sense of distress, or one of disquiet generated by their relationship to their surroundings, the fact that the two figures are seen to hover in space infuses the work with a metaphysical quality. The work’s binary universe references the rift between the social and the individual; the battle between the internal and the external in what is the essential duality of nature; the possibility that the collective might coexist with the personal (or perhaps the impossibility thereof).

While on a trip to Brazil Manolis Baboussis photographed the storage rooms of one of Rio de Janeiro’s many Carnival (Samba) Schools. In the artist’s photographs, these spaces that possess an intrinsic power, not least because of the bizarre, carnival-like character of their contents, seem to erupt before one’s eyes into a singular vision, a metaphor for an uncanny world that has been “stored” out of sight: reality, the natural and the unnatural, the hallucinatory and the grotesque, absence and confinement, all blend to create an otherworldly iconography, which nonetheless documents something that is entirely real; an existing part of this world. The image, fascinating and at once disquieting, illusory, captures the frazzle of this dismantled, ghostly “circus”; of this stillborn ecstasy that is the carnival. A vague sense of sadness (or is it threat?) lurks in the beautiful view of high-rise buildings towering above a screen of tropical vegetation.

Dimitris Tataris’ continued investigations into the mutant spaces of what he calls the “domestic circus” (in the artist’s own words, “all that resides, develops and grows within the range of one’s perception of the world”) are part of a larger narrative that insists on revisiting the notions of fragility and confinement, of arrogance, fear and death, of taming, humanizing nature. In works that bear such characteristic titles as Very Fragile (a reference to the title of his first solo exhibition, Fragile [2008]) and Domestic Circus, a video-and-sound installation, the artist fills a cardboard box (an allegorical “ark”) with fragments of a delicate, unhinged, misshapen world (bones, body parts, pieces of wood, cages, birds, muzzles, the intertwined forms of animals and humans, eyeballs) – it is a view into an inner reality of ruin, desolation and enforcement, where the artist’s persona is at once that of predator and prey, victim and victimizer.

In her video Blown Out, Maria Friberg attempts to foreground the mind’s characteristic tendency to waver and contradict itself. In slow, seemingly eternal motion, a man battles with intimacy and estrangement, with pleasure and pain, with suffering, power and dependence. Still, although he struggles with such antagonistic emotions, he seems to be accepting his isolation and to be at ease with himself. The image of the sea and the waves (a miniature of the outside world) is symbolic of the fear inspired by the likelihood of abandoning ourselves, of yielding, to something much larger than us, be that love, passion, or death.

Katerina Christides’ large scale works aim to transfix viewers, to ensnare them inside their web of narrative that is highly idiosyncratic, both conceptually and in terms of design. The hybrid figures depicted in her curiously genderless portraits inhabit a remote, eerie world, inaccessible and decidedly unfamiliar. They seem caught in a state of psychological uncertainty, grappling with introspection at the same time that they try in vain to conform to a closed structure. Basically, the familiar becomes unfamiliar and the closed form opens up.

Alexandros Psychoulis uses himself, members of his family and of the extended circle of his friends as the heroes of Endless Happiness, where they are seen to endlessly urinate in some non-space. The irony here is obvious: his morbid take on the idea of “happiness” is, on the one hand, a direct, biting comment on the sheer, almost paralytic pleasure one experiences when simply satisfying their bodily functions and, on the other, a brooding reminder of the loss, or implausibility, of happiness. In the end, the image of collective relief, complemented by the irony of the work’s title, only serves to anatomize the universality of suffering.

Katerina Nikou, Thanos Stathopoulos